|

What follows is a short video that gathers together images and sounds I collected around a pop-up exhibition by second year Architecture students. As I have explained elsewhere on this blog, I currently spend every Friday in the Edinburgh School of Architecture and Landscape Architecture where I observe students and tutors as they participate in teaching, learning and assessment. This ties in with my Doctoral research into multimodal assessment across the disciplines.

Across five hours last Friday (14 October) I made dozens of sound recordings and took hundreds of photographs as students set up the gallery, arranged models for display and finally attended an exhibition of their own work, where they were joined by tutors and other members of the architecture school. The work on display comprised more than 2000 models constructed over the first five weeks of the Architectural Design course. Situating myself in the gallery for the afternoon I was able to observe the small archipelago of buildings sprawl into a city-in-miniature, with a broad panorama of approaches and imagination on display. The quality of work can be seen within the images in the video, but is also heard in the excited laughter during the exhibition of work: listen carefully and you might hear a student expressing how proud she is of what the group had achieved.

Through the gathering of aural and visual data I wanted to make a record of the pop-up exhibition that would inform my research: a piece of video ethnography to represent what would have been hard to achieve through written description or images-in-isolation. In the unrehearsed setting of the pop-up exhibition however I was thrust into the role of general exhibition helper. As I swept the floor and cut display paper down to size I gained a better appreciation of what was taking place than would have possible had I sat on the outskirts. If the ethnographer’s main instrument is him- or herself, in this instance it was accompanied by camera and audio recorder, brush and scissors. See also: Architecture, multimodality and the ethnographic monograph Looking beyond photos: the Architectural site visit Listening to the street

0 Comments

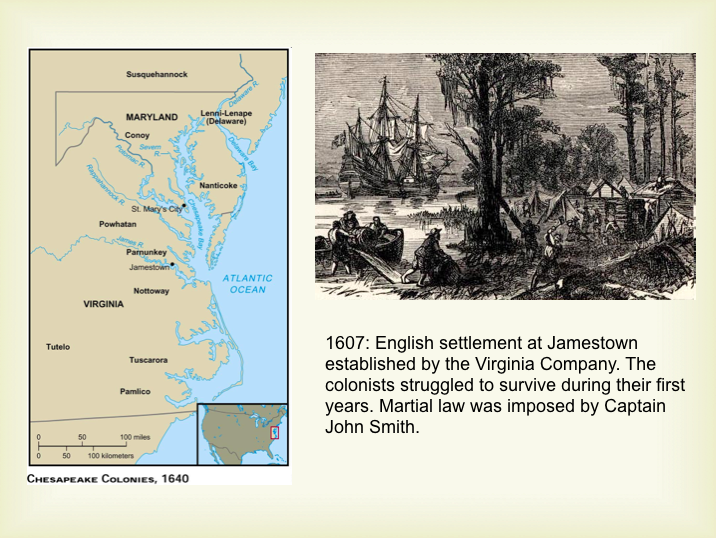

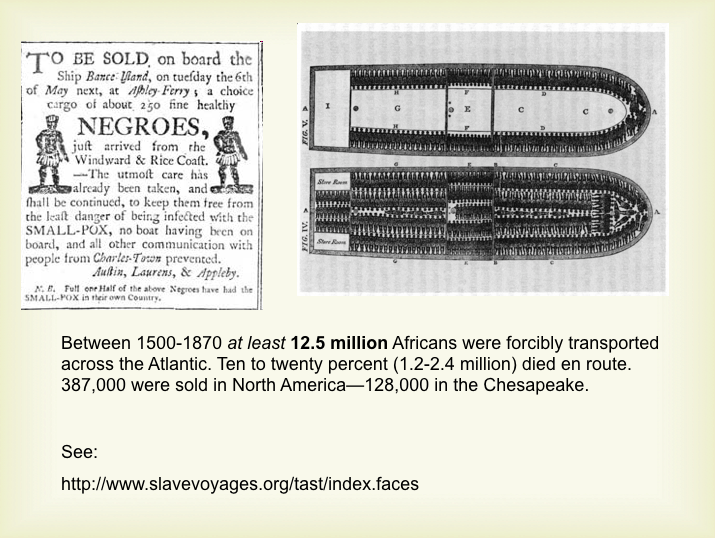

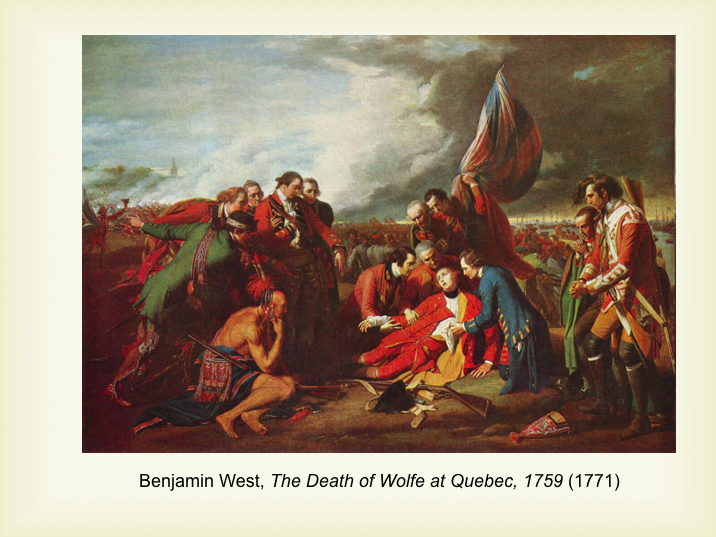

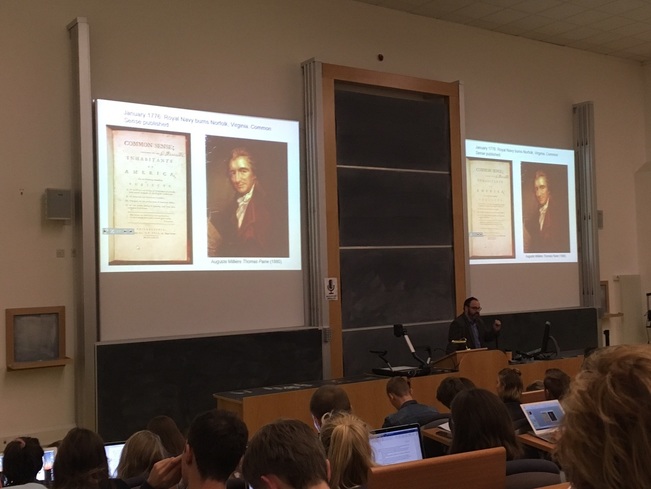

As part of my Doctoral research into multimodal assessment in the Humanities I am undertaking an ethnographic study of an undergraduate American History course. I observe lectures, tutorials and other situations where students and tutors gather to construct meaning, as they explore The Making of the United States of America. There are two reasons I wanted to spend time in a History class. First, in common with the majority of Humanities courses, assessment within History programmes tends to privilege language, commonly in the form of the essay. Second, with its interest in visual artefacts as a means of study - drawings, paintings, maps, photographs - History has an eye for the way that images contribute towards understanding. Bringing these two ideas together, I wondered whether History programmes might be open to assessment practice where attention is paid to the visual, multimodal character of student work. Now that I have reached the third week of the History course (and have a couple of hours before the next class), I am recording some early observations about the role that images have played within classroom teaching. To begin with some context, this is a second year undergraduate course drawing students from a range of degree programmes. Three times a week the lecture theatre is packed with an audience of around 300, augmented by tutorials with groups of around 12 students each. In all of the classes the tutors have used PowerPoint presentations, with images to the fore. Something that really stands out from my field notes is that these images are always more than a backdrop: they appear central to the knowledge that the tutor wishes to convey. For instance:

In these instances the images work alongside the oral delivery, adding colour and context to what is being said. This isn’t to suggest say the lecturer’s oration and wider performance is presented in monochrome: on the contrary it is enthusiastic and eloquent. Simply, the images are vital in helping the tutor to convey meaning. Click on images to enlarge. Slides reproduced with kind permission of Professor Frank Cogliano. On other occasions the images are themselves the central focus of study. Cartoon depictions of individuals and events are used to prompt students to reflect on competing perspectives and attitudes of the time. Newspaper adverts and notices, variously drawing attention to slaves-absconding-or-for-sale, are themselves historical artefacts that demand discussion within the tutorial setting. For the most part the images on screen are accompanied by reasonably small bursts of text (typed words), mostly single sentence captions providing factual information: title, subject, author, date and so on. Three weeks into the course and I have yet to face down a single bullet point. In terms of both prominence and placement, text immediately seems to perform a functional supporting role to the central positioning and critical purpose of the image. This however disregards the presence of text within many of the images: a political proclamation or newspaper notice may be presented in j-peg format however the conveyed meaning is heavily dependent on the use of text. If we narrow our gaze from the slide in its entirety to instead see an image as a communicational act in its own right, we become aware of the intricate assemblage of meaning conveying resources sitting in juxtaposition: text, font, colour, spacing, layout and so on. When this is combined with the tutor’s oral delivery (volume, tone, pitch, pace, silence) and physical performance (eye contact with the audience, gesture, posture, movement across the space behind the lectern) we see that the History classroom is richly multimodal (or ‘densely modal’ to borrow from Norris (2004)) in the way that meaning is conveyed and interpreted. Picturing Thomas Payne in the richly multimodal History classroom In contrast to the highly visual and multimodal character of meaning-making in the classroom, assessment for the American History course privileges the use of written language. Coursework comprises two conventional essays while 20% of the final mark is based upon a ‘practical examination’ in the form of a student’s contribution towards tutorial discussion. To be clear, I am not suggesting that the assessment design is flawed in taking what Newfield (2011) and others might describe as a ‘monomodal’ approach: I am simply drawing attention to the way that it differs from what takes place in the lecture theatre and the tutorial room. When I come to interview course tutors at the end of semester I might find there is a very good reason why measurements of understanding and ability rely on language in its different forms. For the time being however, I have three questions to reflect upon in the coming weeks and months:

Before that however I have a lecture on The Origins of the American Revolution. I expect there to be bullets, but no bullet points. References:

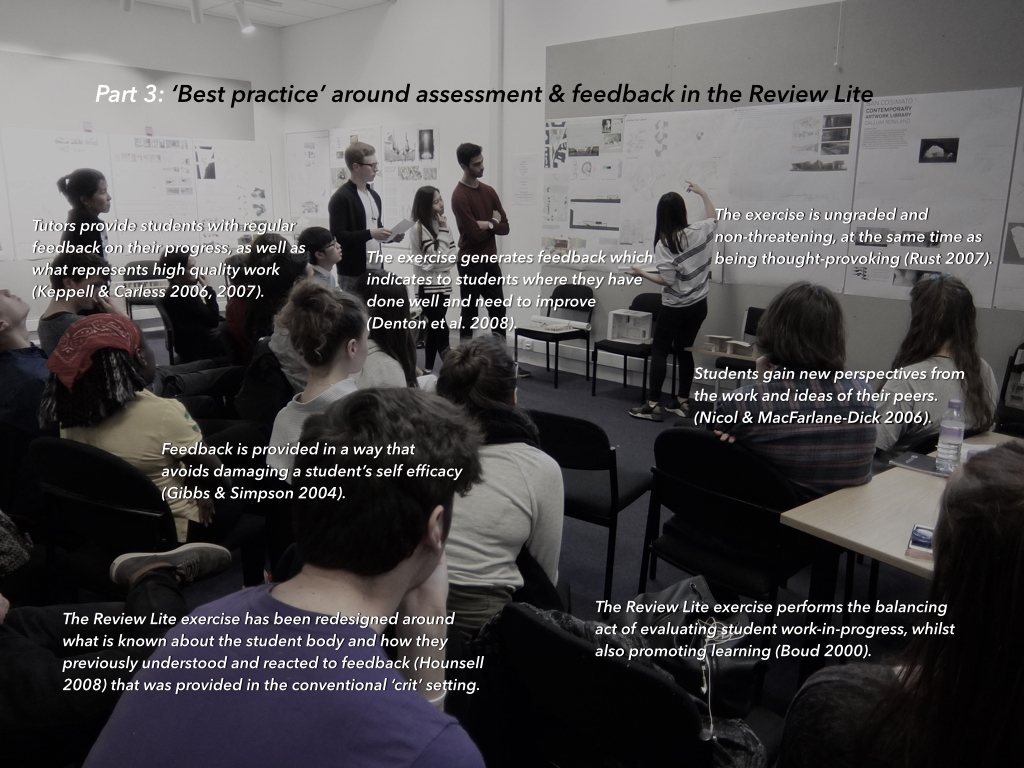

See also: Assessment, feedback and multimodality in Architecture Multimodality and the presentation assignment "I'm just glad it's not an essay!": a poster presentation assignment in music Drawing to a close my recent study of the meaning-making practices of Architecture students, I’m about to make a final visit to the Edinburgh School of Architecture and Landscape Architecture to share the findings of my ethnographic research. It also gives me a chance to observe tutors as they work as a team evaluating the quality of the completed library project portfolios that students have spent the term working on. My invitation this evening has come from Douglas Cruikshank who generously let me spend time observing students and tutors as they participated in a second year course in Architectural Design. I haven’t been quite sure how to pitch my presentation this evening, so I’m going to try and do three things. First of all I’m going to draw on my fieldwork report (my ethnographic study was partly a requirement of a course in Ethnographic Fieldwork that I commenced in January) where I argued that students and tutors enact power in the studio through the conscious use of space and silence. Second I’m going to use the visit as an opportunity to test out some ideas around multimodal meaning making in assessment, which directly aligns with the interest of my Doctoral research. Third, I’m going to try and give something more tangible back to the tutor team by discussing how the pedagogical approaches that I observed over the last three months sit in relation to what we might see as ‘best practice’ around assessment and feedback. Here are my slides: To begin, I should make clear that it was never the intention of my research to critique the practices of tutors, or wider course design or delivery within the Architecture programme. Nevertheless, in the spirit of the ethnographer returning to the field site to share findings that might be important or of interest to his or her participants, I think it’s important to spend a little of bit talking about what I’ve seen. At the same time, this is neither a hardship nor a situation that I need to approach with trepidation, not least as there’s a very positive story to tell. Whether through intentional course design, intuition or luck (although I doubt that), the teaching approaches I have observed during the Architectural Design course would seem to sketch a representative picture of many of the strategies we associate with ‘best practice’ around assessment and feedback. To illustrate this point, I’ve taken the example of the Review Lite, an approach used within the Architectural Design course to replace the intimidating and counter-productive ‘crit’ that has traditionally featured in visually-oriented creative programmes. Using an image I took during the Review Lite exercise I have attempted to show how ongoing tutor feedback, opportunities for experimentation, considering student attitudes, exposure to the work of peer, offering guidance on what represents high quality work - and other strategies - all come together to construct what would seem to on paper (and in my observed experience) to be a formative assessment experience that was highly conducive to learning. Mapping the assessment and feedback literature on 'best practice' against the Review Lite exercise

Between January and March this year I spent time in Edinburgh University’s Architecture School, observing a second year Architectural Design course. Over ten weeks I observed students and tutors involved in an assignment concerned with the design of a library. My interest was in learning how meaning was constructed and conveyed within a creative degree programme. In particular I wanted to gain insights into the ways that tutors and students approached an assessment exercise where work would be conveyed across a range of resources. Now that my ethnographic fieldwork has drawn to a close I have been invited to return to the Architecture School to share my findings. This has prompted me to spend some time thinking about what my experiences in the Architecture studio have to say about the relationship between multimodality and assessment and feedback within a creative setting. Looking back over my field notes and gathered photographs I have identified six themes which seem to stand out as being suggestive of the character of assessment and feedback in the Architecture Studio, as follows: A recurring feature of the Architectural Design course saw students being encouraged to explore relevant themes through drawings and models, which they would then bring to class each week. These artefacts would form the basis of tutorial discussion, where tutors and students would reflect upon the ideas being conveyed through the work. The environment was supportive and students were encouraged to use the preparation of these models and drawings as a way of experimenting conceptually with the design of their library building. At the same time, part of this experimentation pushed students to develop and refine their practical skills: my field notes describe how Maria had been investigating what happened to resin at high temperatures (it burned) and that Ellen had been exploring shape through the use of candle wax. Yet even at this formative stage there was encouragement from tutors towards nicely rendered sketches, polished architectural plans and accurate models: conceptual work and quality of finish. In this setting ‘risk free experimentation' did not mean ‘carefree’: students were encouraged to be ambitious and to bring new ideas and approaches to class, but that their creative energy should be directed towards the the acquisition of understanding and technique which would support their final coursework. This included thinking about the combination of resources that would be most suited to the ideas they wished to convey. This encouragement to be experimental was supported by feedback from tutors that was supportive and made use of dialogue that was in tune with the wider meaning-making rituals of Architecture. By 'In character' feedback I am suggesting that tutors engaged in a dialogue which displayed a symmetry with the approaches and artefacts that were the subject of discussion in class. For instance, when Jack (tutor) wanted to suggest an alternative way for visitors to circulate through Han's proposed library, he sketched directly onto his architectural drawings. Similarly, when Akiko (tutor) wanted Karen to think more deeply about the use of light in her proposed library, she took a pair of scissors and cut through her model to create a cross section that we could all peer into. In each case (and many other similar examples) this was accompanied by an oral commentary. Ideas were constructed and deconstructed using the same techniques for creating and conveying meaning - sketching, modelling, speaking - that students had used to develop their work and will be expected to use in Architectural practice. In the Architecture studio feedback is multimodal as well as in concert with the subject matter and the audience’s needs. From my fieldnotes, meaning was constructed and conveyed through: resin, acrylic, balsa wood, wire, wax, clay, plaster, card, wood, metal. Ink, paint, graphite. Ribbon, wool, netting. Light bulbs and scale plastic figurines. Hand-drawn sketches and computer-aided designwork. Photographs and architectural plans. Gesture, posture, eye contact. Voice. Space and silence. Printed type. Not all at the same time, yet always simultaneously drawing on a wide range of different resources (and more often than not, with words-on-page limited to playing a functional, descriptive role: ‘Scale 1:50’, ‘Elevation’). In the architecture studio meaning is constructed and conveyed in an array of richly multimodal ways, which in turn affects how tutors approach the task of marking assignments. Compared to 'essayistic’ assessment, the rich multimodality of the Architecture portfolio places a greater emphasis on acts of interpretation, rather than more straightforward measurements of quality. Although the marking of a conventional written essay requires the tutor to interpret what is being verbally conveyed, the existence of longstanding conventions around linearity, voice, argument and evidence lend a structure for evaluating the quality of ideas. The portfolio however draws on a combination of resources which speak with a less well articulated language (or indeed, range of languages). And whereas the essay has a pre-fixed format, the tutor evaluating a portfolio is challenged to interpret meaning from a collage of different materials, as the student composer has more freedom to bring her individual interests and talents to the fore. The tutor has to take account of how the different resources come together in concert or collision to create meaning. With a greater attention to freedom and interpretation, it is easy to see why tutors might not wish to work alone when it comes to evaluating and grading coursework... During the Review Lite exercise, students were divided into groups of three and then asked to circulate around the studio, reflecting on the designs being put forward by their peers. They jointly examined and discussed the ideas presented across the sketches and plans on display, before agreeing what they liked about the work and where they felt there was room for improvement. When it comes to assessing the final portfolios, tutors will work in pairs, moving around the studio and discussing how the presented artefacts sit in relation to the brief. In each of these examples the quality of ideas and work on display is evaluated through collaborative discussion between students or tutors. Through conversation and negotiation tutors arrive at an agreed position on how the collected models, sketchbooks and architectural drawings combine to address the assignment brief, followed by the grade that the work merits. When there is a high level of freedom in the representational form of the portfolio (for instance in the selection and use of materials and how they are configured in relation to each other) there would seem to be value in tutors working collaboratively to interpret and evaluate this highly multimodal work. As well as providing room for experimentation and opportunities for dialogue, the high level of student-tutor interaction during the Architectural Design course also seems to plays an important role when it comes to grading the student's overall work. Whereas in many subject areas, and particularly those which heavily privilege verbal communication, marking looks at the submitted work in a form of isolation or separation, a different approach exists in Architecture. In order to account for the learning that has taken place it is necessary to consider how students have approached the preparation of their work, the decisions they have taken and the paths they have followed. The normal university conventions surrounding anonymous marking are waived as tutors necessarily take account of the process as well as the final portfolio that is submitted for assessment. As one tutor described to me, the sketchbook can often be more revealing of the work undertaken and progress made by the student, than the curated final portfolio. If architectural drawings offer an incomplete picture of the learning that has taken place, the time spent together in class affords the opportunity to reflect on process as well as the final product. If we accept that meaning is socially constructed and shaped by cultural circumstances and personal histories, it would seem to make sense for tutors look to evaluate the quality of the work within, as opposed to isolated from, that situation in which it was produced. The six themes that I have described here represent an early attempt on my part to think about the relationship between multimodality and assessment & feedback within the Architecture Studio. Looking to the future I think it would be helpful to investigate whether the same approaches are a feature of other creative degree programmes. Before I do that however I will be sharing these findings when I return to the Architecture School next week. It will be interesting to see whether the Architectural Design tutors recognise the picture I have sketched of the meaning-making rituals that take place in their studio. With thanks to Douglas Cruikshank and the tutors and students within the Edinburgh School of Architecture and Landscape Architecture. Photographs were taken with the consent of the featured students and tutors. Pseudonyms have been used in the place of student names.

A flying visit to London to attend two sessions concerned with multimodality. Yesterday evening (14 April 2016) I visited the London Knowledge Lab for a meeting of the Visual and Multimodal Research Forum, followed today by Multimodality in Social Media and Digital Environments from the New Media Group of the British Association of Applied Linguistics, this time at Queen Mary University of London. My flight back to Edinburgh tonight is delayed so I’m filling the time by gathering my thoughts over an expensive coffee.

At the Visual and Multimodal Research Forum, Dr Elisabetta Adami, University Academic Fellow in Multimodal Communication at the University of Leeds, presented some ongoing research where she is taking a multimodal approach to investigate the experience of super diversity in Kirkgate Market in Leeds city centre. I had the chance to spend some time chatting with Elisabetta in the post-forum debrief where it emerged that we share a number of research interests. First, her work around understanding experiences of the Kirkgate Market isn’t so far from my own interest in how we can take a multimodal approach to understanding our relationship with the urban environment. Add to that Elisabetta's interest in multimodal assessment - she teaches a course on multimodality - and we had lots to talk about. And then today was dedicated to Multimodality in Social Media and Digital Environments where I presented the following paper about tutor experiences of multimodal assessment:

Judging by the conversations which took place over lunch, and the Twitter commentary that accompanied my presentation, my discussion of the ways that multimodality affects assessment seemed to strike a chord:

Now in brief summary - my flight has now moved from red to green on the Departures screen - here are three of the ideas that emerged most strongly from the different presentations, workshops and conversations over the last day-and-a-half.

Flight called. Coffee finished. The journey continues.

With thanks to Sophia Diamantopoulou (University College London), Agnieska Lyons and Colleen Cotter (both Queen Mary University of London) for giving me the chance to attend the sessions described above.

To set the scene, we can describe any presentation or public speaking occasion as a multimodal event in the way that it draws on a range of different semiotic resources to communicate meaning. In fact the presentation setting would seem to be a very effective enactment of Carey Jewitt’s description of multimodality when she proposes that:

This is illustrated in the annotated photograph below, capturing one of the project teams pitching their proposed textile range. Each of the stars in the image represents what we might understand to be a mode, all with their own ‘special powers and effects’ (Kress 2005, p 7) when it comes to the communication of meaning. This includes (but is not limited to) gesture, posture, eye contact, language (written and spoken), image and so on. From there we can go on to look at the meaning carrying potential of typeface, colour and layout within the visual realm, before turning an ear to the signifying power of pitch, volume and tone within the oral dimension. That the different modes are represented through stars is in line with the conceptualisation of multimodality as a 'constellation’ of different resources within a single communicational event (see for instance Carpenter (2009), Flewit et al. (2009) and Merchant (2007)). 'About more than language': Textile Design students use a full range of communication resources to convince us to invest in their bespoke flooring. Looking at the assessment criteria for the presentation exercise, students were encouraged to think about how they could communicate their ideas orally (how they spoke), visually (the content of their PowerPoint slides) and also physically (eye contact and smiling, for instance). Marnie explained to me that the criteria build upon her own professional experience as a textile designer, and recognise the need for her students to "stand up and defend their work in front of clients" in the future. This immediately reminded me of the work of Kimber and Wyatt-Smith (2010) around multimodal assessment, where they emphasise the need for assessment practices to 'authentically' encourage the development of skills that young people will need when they enter the workplace, which includes the ability to think and work creatively. Of course, multimodality is not simply concerned with documenting the different meaning-making resources that are at play, as my annotated image has started to do. As the latter part of Carey Jewitt's definition highlights, we are also interested in the relationship between these different modes, which in turn shapes how meaning is constructed and conveyed. When a presentation is delivered we are influenced by what is said (the words), but at the same time how it is said (pitch, tone and volume for instance) , the accompanying use of body language, the supporting visual content, what the presenter has chosen to wear and other resources that each carry meaning. As an audience we then interpret our own meaning from the combined effects of all the different resources. Consciously or subconsciously, our interpretation might be shaped by how all the different resources cohere (good!) or collide (probably bad). Therefore within a single communicational act - such as a presentation - the different modes sit in relation to each other, not in isolation. With this in mid, to the earlier constellation diagram we can now add all these different lines of interaction, emphasising how the 'inter-modal synergy' as I'm calling it, generates meaning. Inter-Modal Synergy or The Celestial Plough meets Tron To bring this back to the presentations taking place in the Textile Design class, the work I found most convincing was by a team who seemed to have spent time considering how they could convey a message of professionalism through all the different communicational modes stipulated within the assessment criteria. Their oral delivery (spoken 'in character'), the design of their slides (attention to layout, font and white space) and use of physical communication (eye contact with the audience, open body language) seemed to weave together into a single coherent message: "We're serious about this work...now trust us with your money." In contrast, on other occasions the use of spoken language was sometimes out-of-step with the quality of ideas being conveyed within the slides, for instance when a group opened their presentation by asking “Should we introduce ourselves, Marnie?” The spell was broken and I was reminded that I wouldn't, after all, be investing in colour-changing brollies, chic children's clothes or any of the other fabulous ideas that were put forward on the day. Returning for a final time to Carey Jewitt's articulation of multimodality, it is also a useful way of looking at what was not present within the student presentations. Whilst recognising the limitations of what can be achieved within a timed five-minute presentation, and the need to satisfy the stipulated assessment criteria, none of the groups exploited the space of the room as a resource (which Jewitt has elsewhere pointed to as a modal resource, for instance through the ability of teachers to enact power relations by walking around the classroom). At the same time, the tactile qualities of the different products remained trapped on screen. Even though it wasn't anticipated in the assessment criteria, and was perhaps even deemed surplus to requirements bearing in mind the background of the wider audience, I wonder whether teams might have come over as even more assured if they had stepped away from the computer terminal to hand us examples of the textiles they intend to use. Perhaps, though, this is being saved for the assessed exercise next week when the teams will present their wonderfully colourful, creative and multimodal work 'for real'. With thanks to Assistant Professor Marnie Collins and her BA Textile Design students. References:

CARPENTER, R. 2009. Boundary negotiations: electronic environments as interface. Computers and Composition. 26, 138-148. FLEWIT, R., HAMPEL, R., HAUCK, M. and LANCASTER, L. 2009. What are multimodal data and transcription? In The Routledge Handbook of Multimodal Analysis. Jewit, C. (Ed) (London, Routledge): pp. 40-53. KIMBER, K. & WYATT-SMITH, C. 2010. Secondary students' online use and creation of knowledge: Refocusing priorities for quality assessment and learning. Australasian Journal of Education Technology, 26, 607-625. KRESS, G. 2005. Gains and losses: new forms of texts, knowledge and learning. Computers and Composition. 22(1): pp. 5-22. JEWITT, C. 2009. An introduction to multimodality. In The Routledge Handbook of Multimodal Analysis. Jewit, C. (Ed) (London, Routledge): pp. 14-27. MERCHANT, G. 2007. Mind the gap(s): discourses and discontinuity in digital literacies, E- learning, 4 (3), 241-255.

Over the last six weeks I have been undertaking participant observation in the Edinburgh School of Architecture and Landscape Architecture (ESALA) as I have sought to understand how students construct and convey meaning through their design work. This exercise is the subject of an assignment I am completing for an Ethnographic Fieldwork course, whilst at the same time being of direct interest to my Doctoral research where I am investigating multimodal assessment in higher education.

During each visit I spend time observing students as they work on the design of a library building. For the most part my notes have been in ‘text’ form (typed onto my laptop), supported by photographs of models, sketches and other examples of student work. These fieldnotes have worked up to a point, however they haven’t managed to recreate the atmosphere in the design studio: they are muted both figuratively and literally. On my most recent visit to the design studio last Friday, I decided to complement the gathering of words and images, with sounds. To do this, I walked the length of the studio (and then back again) recording sound through the voice memo function on my phone. I wasn’t interested in recording full conversations, but was instead keen to capture the traces of laughter, music, dialogue and other sounds which contribute to the ambient personality of the studio. The subsequent task of ‘writing up’ my notes later the same day also called for a different approach from normal, as I pulled together a short video combining a representative range of audio and images, juxtaposed with extracts from my typed notes. This is what I came up with:

I think the orchestration of images, sounds and words has enabled me to represent the colour and vibrancy of the architecture studio in a way that I wasn’t previously able to achieve. I think this multimodal approach to data gathering and representation offers something different to the conventional monograph with its heavy privileging of words on page. That said, gathering and interpreting visual and aural data presents its own challenges - both practically and critically - and we should remember that photographs and sound recordings are neither neutral nor an accurate recreation of reality. Nevertheless, in light of Architecture’s interest in a wide range of semiotic materials, I wonder whether an ethnographic approach which pays due attention to the aural and visual, is a more apt way of investigating how knowledge is constructed and conveyed in the design studio.

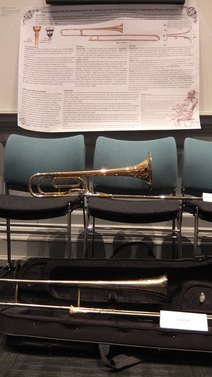

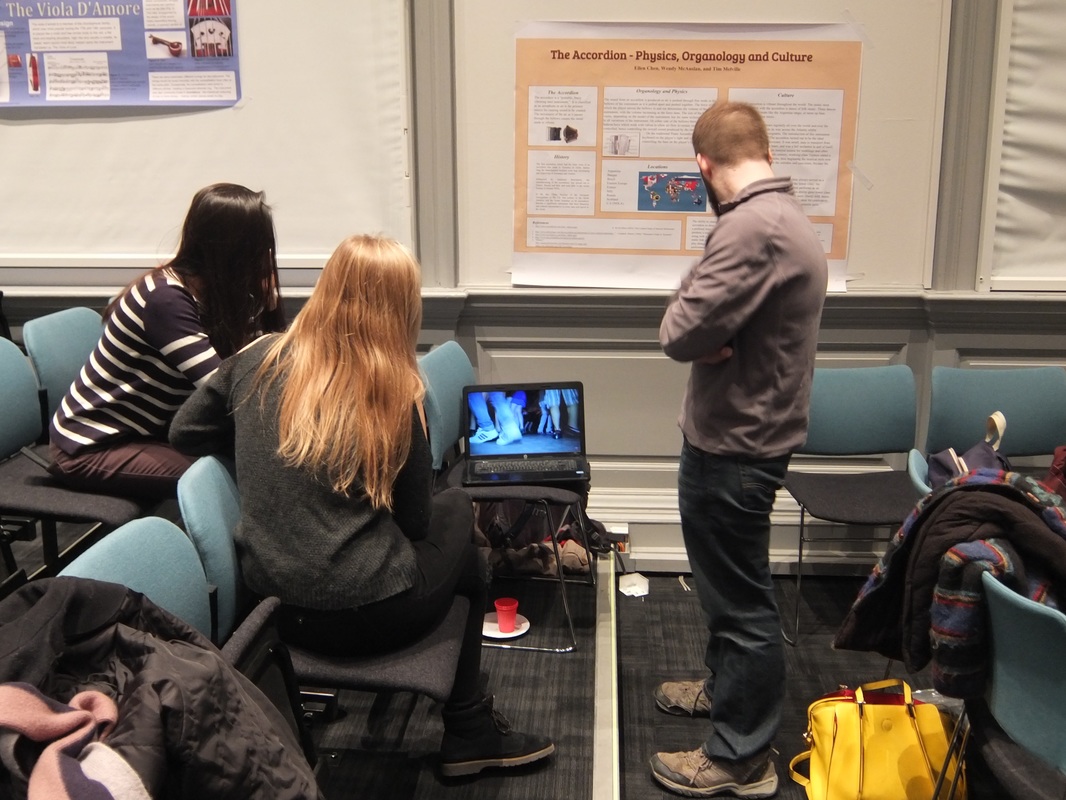

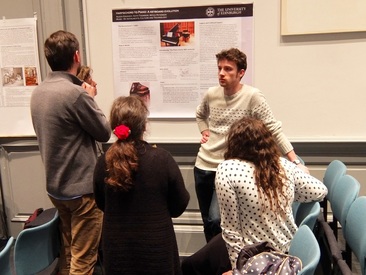

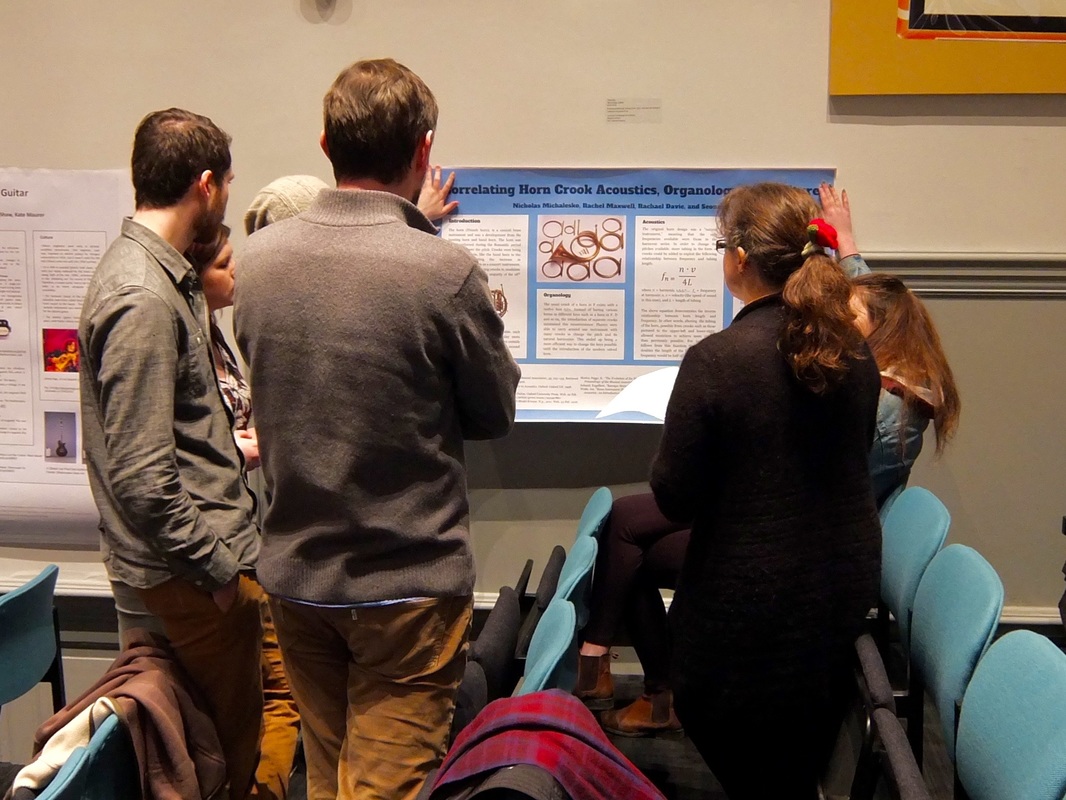

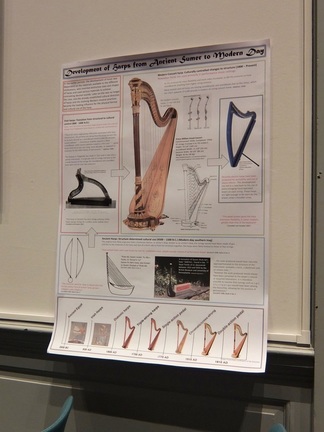

see also: A creative approach to demonstrating success Urban flânerie as multimodal autoethnography I spent yesterday evening at the Edinburgh College of Art, observing students from Edinburgh University’s MA (Hons) Music, as they participated in a poster assessment exercise. The invitation followed a recent interview-over-coffee with Dr Tom Wagner where he generously spent an hour talking enthusiastically about the innovative and evolving nature of assessment on the Music programme. The MA (Hons) Music was originally of interest to me as it’s a degree programme that is simultaneously situated in both the Humanities and what we might describe as the ‘creative disciplines’. The short video on this page neatly describes the distinct nature of the programme. The poster presentation assessment exercise challenged students to work together as they sought to investigate and then present the technical, historical and cultural significance of an instrument on their choice. I now have a greater appreciation of the accordion, hammond organ and Les Paul guitar, although no greater talent for putting any of these fine instruments to good use. The exercise is worth a 40% of the final mark for this particular course so its clear that this falls into the category of high stakes assessment. In an e-mail conversation earlier in the day Tom had revealed a mixture of enthusiasm and anxiety for this first-outing-as-an-assessment exercise and he repeated the “Fingers crossed it works!” mantra when we spoke at the beginning of the evening. My interest was in studying the different ways that students used the poster (and to a lesser extent its presentation) as a way of constructing and conveying meaning. At the same time I was keen to learn how they felt about the experience of putting together a multimodal artefact that drew on a range of resources, including and beyond language. With Tom’s permission I observed and spoke to students before, during and after the presentation of their work. I also took photographs of the posters and the wider class activity (again with permission of staff and the students concerned). Every poster featured a combination of words and images, most commonly pictures of instruments but also what I understood to feature soundwaves and other technical information. Other visual elements included an attention to the use of colour, background and typeface. The posters varied in the extent to which they moved away from what we might think of as the ‘essayistic’ conventions of linearity and a privileging of language. In every instance, printed text featured heavily and there was often a suggested path for me to follow through the poster (and on one occasion a series of arrows in order that I didn’t lose my way). This reminds of research by Lea and Jones (2011) into the practices of students at three UK universities where they found a reluctance to stray far from conventional ways of sharing knowledge. It also echoed the study by McKenna and McAvinia (2011) which pointed to a persistent attachment to linearity amongst students, even when presented we new, digital, creative ways of conveying meaning. This is simply an observation of the posters, not a criticism: indeed, the different groups may have felt that the most effective way of conveying their ideas was to transpose conventional language-based approaches onto the PowerPoint canvas. There were however examples of work where clearer acts of design were on show, for instance where motifs framed the page, or where text was laid over an image of a performing musician. On other occasions the poster itself was placed in juxtaposition with a separate object: a book of organ music sitting on a chair; a selection of trombones laid out parallel to the poster; a laptop with a looping video, which had seen Michael “basically spending about an hour and a half looking for examples of different type of accordion music” in order to show to tutors the variety of ways that the instrument was used. This final example is interesting in that of all the posters I studied, this was the only where the presentation would be accompanied by music. This makes me think of Gunther Kress’s work around aptness of mode (2005) where he proposes that multimodality enables us to consider the particular range of resources that might best convey intended meaning: a poster presentation about the accordion, featuring an accompanying accordion soundtrack, would be seem to be a very effective enactment of this principle. The presentation of the posters meanwhile made use of spoken language, voice, eye contact, gesture and other modes. Perhaps reflecting the high-stakes and unfamiliar nature of the exercise, most students were fairly rigid as they presented their work and arguments to tutors. An alternative explanation is that the layout of the lecture theatre rarely left much room to make use of expressive gesture to support the presentation of ideas. When they weren’t setting up or presenting their posters, many students took the opportunity to look at the work put together by other groups. Unprompted, clusters formed where students gathered to put questions to the authors of the different work. Reflecting on this, Peter described to me how he had “learned lots of new things about different instruments tonight” while a number of students remarked on how impressed they had been with the level of work displayed around the room. “Everything looks really good” Charlotte remarked, while Maria added “Loads of work has gone into this”. There was something really nice about the willingness of students to look beyond their own work: there was a sense of collaborative learning as students constructed a broader knowledge and understanding of their subject from the range of posters and approaches around the room. I was also interested to hear whether the students had any prior experience of putting poster presentations together. Although Karen described “doing this kind of thing in high school”, for the most part the poster exercise was a new approach for almost every member of the class. The exceptions were two self-described ‘visiting students’, who told me that this type of approach had been a feature in their studies in the US. In particular, Carl described his academic background in technical engineering where it was commonplace to use posters as a way of helping to explain potentially complex ideas to an audience. I was also interested to learn how students had found the wider experience of the exercise. Claire’s immediate response, delivered through a mixture of relief and laughter was that “I'm just glad it's not an essay!” which was met with the approval from the rest of her group. This was a feeling that would surface repeatedly in discussion, although two students pointed out that while it worked well in this type of assignment task, “an essay would be better suited on other occasions” (Mark). When pushed on this, Sarah explained “Well, I liked working on the poster as part of a group, but all the decisions you have to make - I’m not sure I would feel so confident doing it on my own”. When asked whether they would like to take this approach in the future, many students were enthusiastic about the poster approach however others suggested that the essay continued to be attractive as it didn't force them to make so many decisions about the form of their work. It was very clear that students had really enjoyed the exercise, and this was the position taken even by those who were nervously awaiting their turn to present the poster to their tutors. It is difficult however to unpick how their enthusiasm for the assignment was attributable to the form of the exercise (presented as a poster), the subject matter (selecting and studying an subject of interest to them) or whether it was the opportunity to work collaboratively. What come through very loudly amongst several groups was how they had enjoyed learning from the drawing on the different interests and talents of fellow group members. This was a point neatly captured by Jimmy who told me “I have an interest in playing guitar, Nico is interested in the technical side and Annie knows about the social side”. Without setting out to critique this exercise, perhaps one of the benefits that it brings (against the preparation of an essay, which one groups told me had been the original intended format for the assignment) is that the presentation element enabled students to describe the critical decisions that had shaped their approach. Tutors were offered insights into the methodology behind the poster they were examining, potentially offering a clearer appreciation of the learning that had taken place. This attention to the process behind the work, as well as the final artefact itself, features prominently in the research literature surrounding multimodality and assessment (for instance in the studies by Breeze (2011), Pandya (2012) and Wyatt-Smith Kimber (2009)) whilst the type of reflection being encouraged and shared by students would seem to echo the how multimodal artefacts can be valuably accompanied by the completion of a reflective essay (see for example by Adsanatham (2012), Barton and Ryan (2014) and Coleman, (2012). Drawing my thought here to a close, what I saw last night was an assessment exercise that had clearly excited students, whilst at the same time challenging them to construct and convey their ideas in new ways. Rather than working in ‘isolation’ on an essay (a situation a number of the students attested to), they had been challenged to work and learn collaboratively. At the same they had been forced out of their comfort zone of music composition and performance, and beyond the familiarity of the written form, to demonstrate understanding through an orchestration of semiotic resources, which required them to undertake acts of design. If student engagement is a vital measure of learning, in an environment driven by outcomes, benchmarking and performativity, importance is also placed on quantifying student progress and understanding. Or to put it another way, the success of this approach will also be measured by asking ‘How did the students do?’ Maybe if I promise Tom another coffee he’ll tell me how he and his colleagues felt about the quality of the poster presentations I enjoyed watching yesterday evening. With thanks to Dr Tom Wagner for his kind invitation to attend and to the students who took time to speak to me and allowed me to photograph their work. I have use pseudonyms in place of the real names of students cited above. References

ADSANATHAM, C. 2012. Integrating Assessment and Instruction: Using Student-Generated Grading Criteria to Evaluate Multimodal Digital Projects. Computers and Composition, 29, 152-174. BARTON, G. & RYAN, M. 2013. Multimodal approaches to reflective teaching and assessment in higher education. Higher Education Research & Development, 33, 409-424. BREEZE, N. 2011. Multimodality: an illuminating approach to unravelling the complexities of composing with ICT? Music Education Research, 13, 389-405. COLEMAN, L. 2012. Incorporating the notion of recontextualisation in academic literacies research: the case of a South African vocational web design and development course. Higher Education Research & Development, 31, 325-338. KRESS, G. 2005. Gains and losses: New forms of texts, knowledge, and learning. Computers and Composition, 22, 5-22. LEA, M. R. & JONES, S. 2011. Digital literacies in higher education: exploring textual and technological practice. Studies in Higher Education, 36, 377-393. McKENNA, C & McAVINIA, C. 2011. Difference and disconuity - making meaning through hypertexts. In Digital Difference: Perspectives on Online Learning. Land, R. and Bayne, S. (Eds) (Rotterdam, Sense Publishers): pp 45-60. PANDYA, J. Z. 2012. Upacking Pandora's Box: Issues in the assessment of English in Learners' Literacy Skills Development in Multimodal Classroom. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 56, 181-185. WYATT-SMITH, C. & KIMBER, K. 2009. Working multimodality: Challenges for assessment. English Teaching: Practice and Critique, 8, 70-90. |

Search categories

All

I am a Lecturer in Digital Education (Education Futures), within the Centre for Research in Digital Education at The University of Edinburgh.

@james858499 james.lamb@ed.ac.uk |