|

A flying visit to London to attend two sessions concerned with multimodality. Yesterday evening (14 April 2016) I visited the London Knowledge Lab for a meeting of the Visual and Multimodal Research Forum, followed today by Multimodality in Social Media and Digital Environments from the New Media Group of the British Association of Applied Linguistics, this time at Queen Mary University of London. My flight back to Edinburgh tonight is delayed so I’m filling the time by gathering my thoughts over an expensive coffee.

At the Visual and Multimodal Research Forum, Dr Elisabetta Adami, University Academic Fellow in Multimodal Communication at the University of Leeds, presented some ongoing research where she is taking a multimodal approach to investigate the experience of super diversity in Kirkgate Market in Leeds city centre. I had the chance to spend some time chatting with Elisabetta in the post-forum debrief where it emerged that we share a number of research interests. First, her work around understanding experiences of the Kirkgate Market isn’t so far from my own interest in how we can take a multimodal approach to understanding our relationship with the urban environment. Add to that Elisabetta's interest in multimodal assessment - she teaches a course on multimodality - and we had lots to talk about. And then today was dedicated to Multimodality in Social Media and Digital Environments where I presented the following paper about tutor experiences of multimodal assessment:

Judging by the conversations which took place over lunch, and the Twitter commentary that accompanied my presentation, my discussion of the ways that multimodality affects assessment seemed to strike a chord:

Now in brief summary - my flight has now moved from red to green on the Departures screen - here are three of the ideas that emerged most strongly from the different presentations, workshops and conversations over the last day-and-a-half.

Flight called. Coffee finished. The journey continues.

With thanks to Sophia Diamantopoulou (University College London), Agnieska Lyons and Colleen Cotter (both Queen Mary University of London) for giving me the chance to attend the sessions described above.

0 Comments

Over the last six weeks I have been undertaking participant observation in the Edinburgh School of Architecture and Landscape Architecture (ESALA) as I have sought to understand how students construct and convey meaning through their design work. This exercise is the subject of an assignment I am completing for an Ethnographic Fieldwork course, whilst at the same time being of direct interest to my Doctoral research where I am investigating multimodal assessment in higher education.

During each visit I spend time observing students as they work on the design of a library building. For the most part my notes have been in ‘text’ form (typed onto my laptop), supported by photographs of models, sketches and other examples of student work. These fieldnotes have worked up to a point, however they haven’t managed to recreate the atmosphere in the design studio: they are muted both figuratively and literally. On my most recent visit to the design studio last Friday, I decided to complement the gathering of words and images, with sounds. To do this, I walked the length of the studio (and then back again) recording sound through the voice memo function on my phone. I wasn’t interested in recording full conversations, but was instead keen to capture the traces of laughter, music, dialogue and other sounds which contribute to the ambient personality of the studio. The subsequent task of ‘writing up’ my notes later the same day also called for a different approach from normal, as I pulled together a short video combining a representative range of audio and images, juxtaposed with extracts from my typed notes. This is what I came up with:

I think the orchestration of images, sounds and words has enabled me to represent the colour and vibrancy of the architecture studio in a way that I wasn’t previously able to achieve. I think this multimodal approach to data gathering and representation offers something different to the conventional monograph with its heavy privileging of words on page. That said, gathering and interpreting visual and aural data presents its own challenges - both practically and critically - and we should remember that photographs and sound recordings are neither neutral nor an accurate recreation of reality. Nevertheless, in light of Architecture’s interest in a wide range of semiotic materials, I wonder whether an ethnographic approach which pays due attention to the aural and visual, is a more apt way of investigating how knowledge is constructed and conveyed in the design studio.

see also: A creative approach to demonstrating success Urban flânerie as multimodal autoethnography As background reading for a conference paper I'm working on, I've been reading about Psychogeography and other approaches to exploring and thinking about urban space. In his engaging (2010) study of the subject, Merlin Coverley presents Psychogeography as being interested in the places where Psychologogy meets Geography. Although 'nebulous and resistant to definition’, Coverley proposes that the different approaches to Psychogeography traverse some areas of common ground, most notably the pursuit of urban walking. This is often accompanied by what Robert MacFarlane (2005) describes as a calling to ‘Record the experience as you go, in whatever medium you favour: film, photograph, manuscript, tape'. How we approach ‘urban’ is also open to interpretation amongst Psychogeographers, shown each weekend in the routes followed along Fife coastal paths, and beyond the periphery of the London Orbital. Just as the city’s boundary is breached by lines of transport and communication, the parameters of what constitutes urban walking becomes blurred. And so a late-December walk through the growing darkness of the west Cumbrian countryside provided an opportunity to document the communications towers and power cables that we encountered on our winding path through the hinterland. The high tension lines pictured ibelow talk to us about the relationship between city and country, at the threshold between Psychology and Geography. It was only at the end of my walk that I became aware of plans to replace the pictured pylons with towers twice the size. At the same time I learned about a resistance campaign amongst residents along the planned route. High tension at the point where Psychology meets Geography. Coverly, M. (2010) Psychogeography. Pocket Essentials, Harpenden.

MacFarlane, R. (2005 ) 'A Road of One's Own'. Times Literary Supplement, October 7.

After fourteen enjoyable years working in widening access at Lothians Equal Access Programme for Schools, I'm about to follow a different path as I embark on a PhD in the School of Education at Edinburgh University. In place of a conventional 'leaving do' I convinced my colleagues instead to finish early on my last day and to take a leisurely stroll around the city, pausing for food, drink and conversation along the way.

The problem with this plan was that an amble around central Edinburgh during the Festival season would involve negotiating crowds of visitors and performers. Instead, I put together a route that would take in some of the city's quieter closes and streets, while at the same time visiting some of the locations that have featured in my working life over the last decade-and-a-half. Fittingly, we began in George Square where I was first interviewed for the job that I'm now leaving. Some hours later our journey drew to a close outside Moray House School of Education where I will take my first classes as a PhD student later this month. To add wider interest to our walk, I proposed that as we passed different sites of interest we should consider how they had changed over time. To help us do this, the night before our excursion I searched through the digital archives of the National Library of Scotland and SCRAN and bookmarked a series of buildings, streets and squares that we would likely pass on our route between George Square and Moray House. The different sites are foregrounded on my iPad in the images below. There's a juxtaposition here not just of new and old buildings, but of traditional and digital approaches to capturing images.

Something I like about the images is the trace of my work colleagues: their hands, cagouls and partial on-screen reflections. Bearing in mind how closely we have worked it was fitting that my colleagues should have a presence within the images. Another thing that strikes me about the images is the occasional lop-sided positioning of the iPad, reflecting the architectural imperfections and character that make up this part the city.

I also captured a short ambient audio recording at each site we visited. In a second representation of the collected data, the video below combines the sight and sounds of each of our stopping points.

I think the video-montage offers alternative insights into the same locations captured in the earlier slideshow. An obvious example would be how our journey was accompanied by the almost constant hum of traffic, even when there were few or no cars in view. Elsewhere, the sound of music, a child crying and a passing conversation about a visit to the zoo reveal a warmth, humour and emotion that isn't always present when we consider the photos in isolation.

The way that the introduction of sound contests the impression of contemporary Edinburgh presented in the slideshow prompts me in turn to consider whether the same rules might apply to the archived images. Or to put it another way, if we somehow had access to sound recordings taken at the time of the photographs of old Edinburgh, would we draw different conclusions about the stories that appear to be unfolding in some of the images? I wonder whether our understanding of how we used to live that we take from the apparent calm and tidy order of the archived images, would change if we were to hear the sounds pouring from the sepia-tinged breweries, printworks and classrooms that characterised Edinburgh's Southside a hundred years ago? See also: Urban flanerie as multimodal autoethnography and EC1: sights and sounds The sights and sounds of Portsmouth and Southsea Ultras EH9: Fan culture in south Edinburgh Maps, music and augmented reality The sights and sounds of matchday: FC St Pauli in Hamburg Last November the brilliant Cities and Memory sound archive set out to capture the distinctive sounds that accompany a major football match. The audio exercise is described in 'The living nightmare of the Arsenal fan' where Stuart Fowkes tells how he captured and then remixed the sounds of the Champions League contest between Arsenal and Anderlecht at the Emirates Stadium. What Stuart's exercise didn’t set out to do was gather the wider sounds of matchday, including the chaotic mixture of conversation and chanting that can be heard before and after the game, and which contribute massively to the experience of watching live football. At the same time Cities and Memory is essentially concerned with sound and therefore didn’t gather images to accompany the changing pitch as the game unfolded. What follows then is my own attempt to bring together the combined aural and visual colour of matchday. The fixture was FC St Pauli versus VFL Bochum in the second tier of Germany's Bundesliga. I've been making visits to St Pauli's Millerntor Stadion for the last decade, always spending the weekend in Hamburg in order to get the full experience around the game. This meant that I had a good idea of where and when I might find interesting and representative soundclips and photographs. That said, the pattern of matchday was dictated by the game itself, not by my data gathering. After all, if St Pauli were to lose this final home game of the season, they would be relegated to the third tier of German football. The high stakes nature of the match meant that I didn’t take as many photos during the game as I would have liked: it’s one thing to bring a camera to the game, but I wasn't willing to intrude on the occasionally fraught experience being enjoyed/suffered by the fans around me on the Sudtribune. My commitment to ethnography lasted only until St Pauli conceded in the opening minutes of the game, at which point there were more serious matters at hand. There was also room for serendipity, for instance in the way that my pre-match wander to the St Pauli Fischmarkt coincided with an assembly of several hundred Bochum fans who lit flares, unfurled banners and chanted songs before making their way en masse to the game. At the same time there's always the possibility that a visit to the Millerntor Stadion will lead to new friendships, pub visits and parties that couldn't be scripted at the start of the day. I’m not going to describe the assembled images and audio, other than to say they are gathered below within a series of montages that depict pre-match, the game itself, and then the post-match celebration (look out for scoreboard and listen to the sense of disbelief within the middle montage). The slide shows play automatically and you can click on the audio player to hear the accompanying cries, songs and laughter of matchday St Pauli. Pre-match tension90+3Post-match partyLooking back at the gathered sights and sounds here, I think they go a good job of documenting what we experienced before, during and after the game. The images and audio clips go some way to capturing what is special about watching live football (in Hamburg, at least). The colour, humour and camaraderie are a reward for those who embrace matchday, rather than choosing to spectate from the comfort of the pub or armchair. Something that isn't captured above however is the next-morning-remorse that comes from one Currywurst too many, or the echo of fansong that repeats in our heads for the whole of the flight back to Scotland and the days that follow. Forza-Sankt-Pauli! Forza-Sankt-Pauli!, Oh! Forza-Sankt-Pauli! It’s still ringing. With thanks to our friends at Fanladen St Pauli for help with tickets and the cool folk in Café Absurd for letting us capture the sounds of a lock-in.

Taking place later today is the Scottish Funding Council's annual Learning for All conference. The conference provides an opportunity for widening access practitioners to stand up and draw the attention of colleagues and funding bodies to some of the successes they have experienced over the previous year. This year, along with my LEAPS colleague Alice Smith, we will be telling the story of the Creative Extras programme that she created and coordinated last Autumn. Very briefly, Creative Extras comprised a week of workshops and other practical sessions at a range of different universities and gallery spaces in Edinburgh and further afield. Talented young artists and designers gained invaluable preparation for higher education, whilst carrying out portfolio preparation under the guidance of undergraduates and tutors. My only significant input to the week was putting together a short video to record and celebrate the story of the week. From recollection, the rationale supporting the creation of a video was two-fold. We primarily wanted to document the distinct character and atmosphere of the week in a way that wouldn't easily be captured through the conventional reporting of text and photographs. We were coming from the position that established approaches to evaluation and reporting couldn't adequately tell the story or capture the vibrant colour and noise of this particular part of our work. We wanted to be a bit more creative with our reporting. Tied in with this, we wanted a video that could be shown at the exhibition of student work that would draw the Creative Extras programme to a close. And so across the week we took photographs and recorded conversations and background noise as the different sessions took place. To get back to the Learning for All conference, rather than standing up and talking around a set of PowerPoint slides - another conventional way of reporting success - we're simply going to press 'Play'. We'll be showing the video to demonstrate the success and imagination of the Creative Extras programme, however another hoped-for benefit is that the nature of the video will in itself demonstrate the creative and considered approach we take in our work more generally. In effect, the representational form of the video becomes the argument: it is thoughtful and imaginative and, we believe, so are we.

Perhaps the process of making the Creative Extras video reflects the opportunity to be creative within digital educational environments. Without any formal training or expensive equipment, we were able to put together a video in a way that would have been beyond our capabilities and budget a few years ago. At the same, in an increasingly visual culture, we were confident that the video would be a valid and appropriate way of helping to demonstrate the success of the programme that is captured in the orchestration of photographs and sounds. Kathleen Fitzpatrick (2011) calls for a rethink in how academic knowledge is presented, in that we look beyond the linear, text-dominated form: I think our video is a nod in that direction, even if we weren't bound to the publishing pressures that can confine how ideas are shared. It will be interesting to see whether our colleagues at today's conference are similarly open to this creative way of demonstrating success. References

The video features photographs by Sarah Austen, Emma Caldwell, James Lamb, Alice Smith, Scott Willis and The Fruitmarket Gallery. The audio was recorded by Emma Caldwell and James Lamb. The soundtrack was created by Emma Caldwell and James Lamb. In the last couple of weeks Michael Sean Gallagher and I have been adding the final touches to a book chapter which explores The Sonic Spaces of Online Distance Students. Working with our mentor Professor Siân Bayne from the University of Edinburgh, we have proposed a methodology which uses aural and visual data as a way of understanding how online distance students construct space for studying. The chapter will feature in a wider text concerned with place-based learning that will be published later this year, however this is a subject that Michael and I have been researching and thinking about since 2010. Our chapter revisits data that Michael and I collected as part of the New Geographies of Learning project that we worked on together in 2011. Along with our colleagues from the MSc in Digital Education at Edinburgh University, we prepared two published papers from this work (references below). We also generated a series of 'digital postcards', where we invited online distance students to 'capture' a space from where they typically engaged with their programme of study. The postcards were digital in the sense that they each combined a photograph, short text description and an audio field recording of the same space. It was this audio and visual data that Michael, Siân and I returned to look at in more detail within our book chapter. Although the ink is still drying on the print and photographs that make up our chapter, earlier this week Dr Louise Connelly from the Institute of Education at The University of Edinburgh gave us the opportunity to talk about our work as part of her online tutoring course for staff. You can look at my slides from the session, however what you'll learn from a series of images that depict soft furnishings, I'm not sure. The central thrust of our webinar was a discussion of the methodology we devised. Key to our thinking was to avoid the tendency amongst Internet scholars to privilege image over sound (Sterne 2006), and to instead think about the interdependency, cohesion and conflict between different semiotic material. In the absence of an existing approach to transcription or analysis that suited our needs, we developed our own approach by drawing on a range of methodologies concerned with aural and visual data, and the relationship between different semiotic modes. In brief summary we:

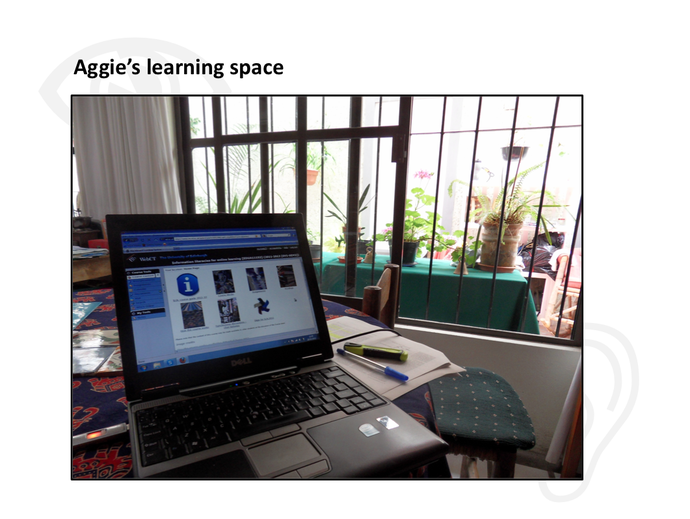

To demonstrate our methodology during Monday's webinar, we invited participants to look at examples of data gathered within the New Georgraphies of Learning project. This included thinking about the digital postcard submitted by Aggie, an online distance student based in Mexico, but completing a programme at Edinburgh University. We invited participants in the webinar to reflect on whether there was anything interesting, surprising or seemingly significant about the study space captured in this postcard image: Using the Chat function in Collaborate we then asked the group to share their ideas about the study space in the photograph. There were more thought-provoking observations than I have room to include here, however it was interesting to note that a number of themes that Michael and I found to be present in the wider data set (i.e. across many of the 15 submitted postcards) arose during the webinar discussion. This included:

In the second part of the exercise, we invited the group to look at the image once again, but this time whilst listening to the audio clip that Aggie submitted to accompany her image: As we listened to the orchestration of birdsong, distant brass music, children-at-play and the chopping-of-vegetables that feature in Aggie's field recording, fascinating strands of conversation developed within the Chat box. This included differing positions on what represents 'noise', and whether music can be used to usefully construct spaces that are conducive to studying. Both of these themes are discussed within our forthcoming chapter. What was also interesting was the way that conversation moved onto discuss whether the insights gained from our methodology might practically inform course design and teaching of online distance courses. I have reproduced some of the comments below in order to give a feel for the nature of the discussion.

Within our chapter, Michael, Siân and I have been clear to avoid suggesting that the themes to emerge from our transcription and analysis of the digital postcards necessarily sets hard-and-fast rules about the ways that online students use sound and physical material to construct spaces for studying. What we did propose though was that this type of data - and our methodology - offers new ways of thinking about the nature of these spaces. I think that the conversation reproduced above helps to support this.

If we were to deliver this session again - and I really hope we get the chance to do so as it was great fun and opened up new lines of investigation - I would leave more time for participants to reflect on whether and how the introduction of the aural data altered original impressions of the study space captured in the image. It's clear that listening to Aggie's sound clip enabled the group to see beyond the edges of the photograph, however I think we missed an opportunity to really discuss how the interplay between the aural and the visual data potentially generated meaning over and above the impressions we might have taken from these individual modes. As I mentioned in my introduction, Michael and I have been discussing the nature of online study spaces for close to 5 years: I think this week's webinar suggests there's value in continuing the conversation. References

In this post I describe and a recent exercise where I used photographs and interviews in order to gain insights into the digital lives of teenagers. To offer some background, in the first four months of 2015 I have been developing a digital strategy to support my work in widening access. I have been exploring how digital environments, pedagogies and technologies might enable my colleagues and I to extend and enhance our support of teenagers as they consider and then apply to higher education. One of the approaches I have been taking is to speak directly with school students. If this seems an obvious point, in It’s Complicated: the social lives of networked teens (2014), Danah Boyd bemoans the tendency for adults – educators, politicians, journalists – to discuss the digital interests and needs of young people without stopping to listen to the same people to whom they are variously attaching labels and planning courses of action. More locally, at the recent Jisc Digital Student Consultation in Edinburgh, there was a clear message that students want to be asked, in a meaningful way, what they need from technology. Focus groups had pointed towards a feeling amongst some students that institutions wanted to be seen to be listening, without actually listening. To open some dialogue with the particular pre-higher education audience that I work to support, yesterday evening I took advantage of a conference for S5 school students being staged by my colleagues on Edinburgh University's campus. With a fairly small window in which to speak to attendees, combined with my wish to avoid intruding on the Conference itself, I took the following approaches to data collection:

I approached students directly before the Conference opened, as they enjoyed light (non-alcoholic) refreshments in the Student Union. This noisy and informal setting lent itself well to encouraging them to talk about their use of social media, attitudes towards email, access to the Internet, and other questions drawn from the literature and my own research. This approach also had the desired effect of enabling me to collect a lot of data in a short period of time. In less than an hour I spoke to 25 students as well as photographing the digital devices they had brought to the event. Without having taken time to really consider the data in depth, a cursory glance and listen to the different responses and conversations suggests the following:

Naturally the data merits much deeper consideration than the immediate observations I've outlined above. But I'm also interested in thinking more generally about whether there is anything I can take away from the exercise from a methodological perspective. For instance, I'm wondering whether photographing visual devices can be an effective way of addressing the potential for some students to overstate the digital resources they can call on (as a number of colleagues had described, during an earlier stage of my research). Admittedly, a student who owned a hand-me-down Nokia 8210 might simply have not presented it to be photographed, but he or she wouldn’t have been able to conjure up an iPhone 6 in its place, in the same way that it is possible to make over-inflated claims within a conventional focus group or questionnaire.

References

[All data reproduced with the written consent of participating students]

Over the last two years I’ve been recording traces of football fan culture in my neighbourhood, to the south of Edinburgh’s city centre. This exercise initially came about through a desire to try out a new camera, combined with the fact that pushing my 2 year-old son around in his buggy was a sure-fire way of getting him off to sleep. Hundreds of miles and hours later I've decided to share some of the photos and stories they tell. I've collected the most interesting images in a slideshow below and then, further down, have mapped them onto the streets of Edinburgh's Southside.

From a few different places in Marchmont - within Edinburgh's EH9 postcode district - you can look north to Edinburgh Castle, before turning east towards the volcanic rock of Arthur's Seat. The Castle and Arthur's Seat: the royalty of postcard Edinburgh. Maybe more interesting though (to me anyway) is the ephemera and milieu that says something about the city right now. At the danger of over-simplifying things, The Castle tells us about history whereas the streets are part of an unfolding story.

Through repeated excursions I became aware of colourful stickers attached to lampposts, recycling bins and other bits of everyday street furniture. If this sounds like an unglamorous pursuit, on the contrary I encountered Danny Kaye and Johnny Cash as I walked the lines of tenements that characterise my neighbourhood. Some of the most interesting stickers were those bearing the identity of football Ultra groups. Ultras, in case their existence is new to you, are groups of highly organised and often politically-motivated football fanatics. They have an investment in their chosen club that goes beyond the 90-minutes-plus-time-added-on and manifests through colourful choreography, carefully crafted banners and controversy. There will frequently be fireworks when Ultras assemble in their chosen area of the stadium. Looking beyond the imagination and humour of some of the stickers, I was interested in the way that their presence felt out-of-step with the calm order of the residential streets, schools and shops where I found them. Marchmont isn’t Merseyside and The Meadows is a long way from the Maracana, both figuratively and literally. To illustrate the point in a very blunt way, I’ve never queued behind the Green Brigade at the cash point on Thirlestane Road or nervously exchanged glances with Ultras Nurnberg on Bruntsfield Place on my way to get the croissants. And yet their presence was to be found attached to the physical material of the street - in fact they became a part of it's materiality, its personality. As I became aware of this curious jarring I changed my approach and set out to record each sticker against the backdrop of its surroundings. This resulted in some amusing juxtaposition that wasn’t always apparent at the time: aggression in front of a place of worship; a zombie gathering set against a leisurely family outing.

Hover over the map and then a hotspot to view a low res picture of a sticker in it's location.

Over time these vinyl calling cards became more commonplace and I altered and extended my excursions to take in different paths, parks and other public spaces. The derelict land and industrial units around the Union Canal evoked a battleground as different Ultra groups competed for eminence. The message was clear: our football might be mediocre on the pitch but our fan artistry rises above all others (and is placed high enough up this lamppost to make it difficult for rival fans to deface or remove it). South Clerk Street presented a similar story of conflict as the different sides of the road became the opposing ends of a football ground: Hibs versus Hearts at Easter Road, at Tynecastle and then spilling out onto the lampposts and postboxes of the Southside.

There was also serendipity in this documenting of fan culture. Without it ever being my intention a number of photos taken during the Summer and Autumn of 2014 inadvertently revealed the political climate in Scotland at the time. When the story of Scotland’s independence referendum is told it’s likely that it will be accompanied by images of politicians, press calls and orchestrated mass rallies. What will mostly be overlooked, I imagine, is the everyday appropriation of the street, as citizens of different hues pinned their sticky-backed colours to the lampposts and signs of their neighbourhoods. Better Together with the Union Bears. Another Scotland is possible with the Brigade Loire. And they say football and politics don’t mix. If there’s any value in this exercise (beyond learning how to use my camera and helping my son off to sleep) it’s that this approach can tell a story about what was unfolding within a specific part of the city over a particular period of time. Perhaps the gathered images can be seen as a capturing of the moment that will be overlooked in conventional histories of Edinburgh, and in the websites and brochures that are used to entice visitors and investors. If Edinburgh Castle and Arthur’s Seat are immovable rocks in the city’s landscape, there's also value to be found in turning an eye to the ephemeral: the minutiae of our everyday surroundings that capture what’s happening, rather than what has happened. Divert your gaze from the city’s landmarks and study the detail of your neighbourhood. The terraces have a story to tell. See also: The Sights and Sounds of matchday: FC St Pauli Multimodal wandering/wondering in EC1 The Sights and Sounds of Portsmouth & Southsea Last week I attended the MODE Multimodal Methodologies Conference at University College London. I won’t summarise the Conference here as that’s better done by visiting the designated #modeME Twitter hashtag. What I will say is that the value of proceedings can be measured in the attendance during the closing session, which was at least as busy as the opening address. Alongside my colleagues Michael Sean Gallagher and Jeremy Knox I contributed a session proposing Urban Flânerie as Multimodal Autoethnography. The rationale behind the paper is explained in an entry I wrote directly before the Conference. Our presentation slides can be viewed here. In the absence of text or accompanying voice however, I’ve included below some Twitter feedback which captures some of the main points we put across. Within the 30-minute presentation slot it was only possible to share a fraction of the images and sounds that we had collected the previous day. Gathered at the top of this entry, then, is a juxtaposition of some of the sights (captured in a slideshow) and sounds (within the audio montage) of EC1. For me, the most significant themes to emerge from our exercise in Multimodal Flânerie are as follows:

Inevitably, we could improve the exercise next time around (and we intend to). I would use a better quality Microphone to capture the aural data [actioned]. I would also make a written note of the locations where we gathered data. And I wouldn’t have a pint at lunchtime knowing that I needed to work on the data later that night (a Gin & Tonic would be acceptable, though). Finally, a spin off from our exercise. I drew our presentation to a close by proposing that those with an interest in our methodology could join us for an exercise in flânerie that evening, as we made our way from the Conference venue to a nearby pub. And so amidst the neon, sirens, and crowds of Euston and its surrounds, we captured some interesting sights and sounds. I’ve put this data into a short, sketchy video that captures our journey from A to B (although invoking the spirit of the flaneur, not by the most direct route, obviously). |

Search categories

All

I am a Lecturer in Digital Education (Education Futures), within the Centre for Research in Digital Education at The University of Edinburgh.

@james858499 james.lamb@ed.ac.uk |