|

Earlier today I contributed to an online seminar organised by Mathian Decuypere, Karmijn Van De Oudeweetering (KU Leuven) and Sigrid Hartong (Helmut-Schmidt-University Hamburg). The event brought together a range of researchers who are using theories of social topology to explore the nature of space and time within educational contexts. For my part, I talked about a piece of research I have been working on with Jen Ross where we investigated how lecture capture technologies affect the spatial and temporal arrangements of higher education (full title on the image below). Where much of the research around lecture capture has explored its impact upon attendance or assessment, we instead used it to cast a light on the relationship between technology and space, and time. To help us do this we turned to conversation talking place on the Twitter social networking platform. Across a 3-month period between mid-February and mid-May earlier this year we collected more than 550 tweets that discussed lecture capture in the context of higher education. Although conversation was dominated by academic staff and students, lecture capture was also a topic of interest among learning technologists, educational developers, ed tech providers, consultants, accessibility advisers, professional bodies, representative unions and other groups and individuals. We identified 29 different lines of conversation which conceptualised or considered lecture capture in terms of pedagogy, politics, profit, the Covid-19 Pandemic and beyond.

Jen and I hope that our work will be published later this year therefore I won't go into detail for now. What I will say, however, is that lecture capture, in relation to a range of other interests, pressures, resources and constraints, was shown to both shape, and be shaped by, the spaces and times of higher education. Lecture capture, we argue, contributed towards the formation of new educational environments: the kitchen and couch became central teaching spaces, as the lectern and lecture theatre sat in lockdown-darkness. At the same time, as staff pre-recorded content which was then made available by video, the synchronicity and timetabling that have for so long shaped the nature and rhythm of teaching and learning was disrupted. Instead, the lecture became dispersed over a greater period of time, while students also negotiated different temporalities to support their particular learning needs or preferences. More to follow later this year.

0 Comments

Earlier this year I completed my ESRC-funded PhD research which investigated the relationship between technology and the learning spaces of higher education. Prompted by a recent conversation among colleagues here at Edinburgh University about the potential of the digital dissertation, in this post I explain how my own thesis was presented in multimodal and digital form.

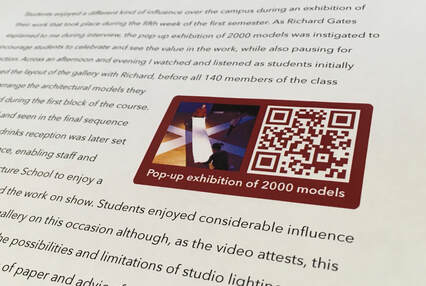

By ‘digital dissertation’, I am referring to the presentation of scholarship in overtly digital and multimodal form in those contexts where work is normally conveyed in a more essayistic and language-privileging format. At least in the arts, humanities and social sciences, it remains difficult to move beyond traditional print-based conventions within the high-stakes assessment setting. In the case of my own thesis, I sought to balance my desire to produce a richly multimodal and digital artefact, with University regulations and tacit disciplinary expectations around the exposition of knowledge. My wish to produce a digital dissertation came partly from my interest in multimodal assessment, as I have discussed in this journal article, this conference key note and other workshops with academic teachers. More important, though, was finding a representational format that would foreground the sonic and visual data around which much of my PhD was built. As I argue in the thesis itself, sound has tended to exist on the periphery of qualitative research (as discussed by Dicks et al. 2011) while the critical value of audio data has been undermined by a lack of consideration when reproducing sonic material alongside more conventional published researched (see in particular Feld & Brenneis 2004). The challenge I faced was to present audio and visual content in juxtaposition with written argumentation, while at the same time satisfying University regulations around the preparation of a traditional word-processed thesis. My response was to insert QR codes that linked to different types of digital artefacts. As I explained to the reader in the opening pages of my thesis, the intention here was that they could use a smartphone to access digital material alongside the printed content. True to one of the key ideas of multimodality, argumentation was made through the simultaneous juxtaposition of semiotic material, for instance words, images and sounds.

Therefore where my research involved the use of playlists as ethnographic artefacts, the reader was able to sample the nominated songs alongside my discussion of insights they had provoked into the way that learners used music to negotiate different types of learning spaces. These playlists – one for each of the American History and Architectural Design courses that provided the setting for my research - were hosted on the music-sharing platform Mixcloud. Here is the playlist I created with Architecture students:

Meanwhile in order to convey the sonic character of different teaching spaces, I created interactive sounds maps in Thinglink that situated ambient audio recordings and photographs against corresponding locations within diagrammatic floor plans. Here is the sound map for the area of the design studio where much of my field work took place:

Across more than a year of ethnographic field work I generated several hundred audio recording and thousands of photographs, some of which formed the basis of 15 short videos. Each video combined audio recordings, photographs and excerpts drawn either from my written field notes or from interviews. The following video captures the sights and sound of the architecture studio:

The creation of these different digital artefacts, combined with the way that they could be access via QR code, goes some way to showing how even within the constraints of producing a printed dissertation, it is possible to craft an artefact in digital, multimodal form. An important influence on my approach here was Kress’ work around aptness of mode (2005), the premise of which is that the digital form allows us to consider how we might shape the representational form of a digital artefact in a way that helps to best present the knowledge that is to be communicated. This meant producing a digital, multimodal thesis not for the purpose of experimentation, but rather because it was the most suitable way of executing arguments around the relationship between sound and physical space.

There are sure to be other and more imaginative examples of what a digital thesis can look and sound like, particularly when they emerge from the creative disciplines or within interdisciplinary contexts. And while my use of QR codes (rather than embedded content) may have been a neat concession to University regulations, it does feel like a compromise rather than a true use of the digital form. Nevertheless, I hope that my approach helps to stimulate more conversation about what is possible when it comes to producing richly digital and multimodal scholarship in an assessment setting, perhaps even contributing to conditions that are more conducive to this kind of work. References

The Manifesto for Teaching Online, created by the digital education team here at Edinburgh University, takes a position and provokes debate around what we believe to be the vital trends in the relationship between contemporary education and technology. In this new article within Digital Culture & Education, Jen Ross, Sian Bayne and I talk about the evolution of the manifesto (it was first created in 2011 and then reimagined in 2016), including the reaction is has generated among the academic community. As our abstract describes:

By comparing the statements that made up each version of the manifesto, our article helps to surface how the critical questions around digital education have evolved in a relatively short period of time. At the same time, the article demonstrates how the non-traditional form of the manifesto - in each instance it has been punchily presented via postcard, video and website rather than conventional academic discourse - can in itself help to expose some of issues that we believe are central to the changing nature of digital education.

Ross, J., Bayne, S., Lamb, J (2019). Critical approaches to valuing digital education: learning with and from the Manifesto for Teaching Online. Digital Culture & Education, 11(1), 22-35 URL: https://www.digitalcultureandeducation.com/volume-11/

This semester I am teaching on the An Introduction to Digital Environment for Learning course, part of the MSc in Digital Education at Edinburgh University. One of the objectives of our course is to provide students with an opportunity to experience a range of digital settings where teaching and learning take place. Going further, one of the blocks in our course is devoted to investigating the relationship between education, technology and space. Among other activities, students spend time exploring and building in Minecraft, while at the same time reflecting upon its potential to support learning.

To coincide with these activities, I spent time speaking with Tom Flint, Lecturer in Digital Media and Interaction Design at Edinburgh Napier University. The subject of our conversation was Tom's co-authored work around the creation in Minecraft of a facsimile of the Jupiter Artland scultpure park (Flint et al. 2018).

This shortened version of our conversation, juxtaposed with some of my own photographs and field recordings from Jupiter Artland and elsewhere, is one of the resources we are using in the An Introduction to Digital Environment for Learning course as we help students to think about the complex relationship between education, technology and space.

Perhaps the most interesting theme to emerge from my conversation with Tom was that we need to think of physical and networked environments as co-constituting, or what Nordquist & Laing (2015) and others have referred to as 'hybrid learning spaces'. When digital technologies have become so much a part of our everyday surroundings, perhaps there is a case for drawing on post-digital thinking (see Jandrić et al. for an introduction) to recognise the way that digital and physical environments are woven together into what we might call 'post-digital learning spaces'. Instead of thinking about either 'physical' or 'online' learning environments, perhaps we should instead recognise that many educational settings are shaped by spatial dimensions and the configuration of furniture, but also simultaneously by the flow of data and access to screen-mediated content.

I have been a little slow to share this article, published in Qualitative Research at the end of 2018, that I wrote with my colleagues Michael Gallagher and Jeremy Knox. It reports on a methodological exercise we took in London where we brought together ethnography, multimodality and urban walking. This involved making an unscripted walk through central London that we attempted to document through photographs and field recordings. This video goes some way to capturing what we did.

In the moments after drawing our excursion to a close, Michael, Jeremy and I began working through the data, generating some ideas that we presented at a conference the next morning (and we discuss in our article). This includes the potentialities of combining urban walking and ethnography, but also the limitations in our attempt to generate data as a way of reflecting on our relationship with the city.

Since undertaking that first exercise in London, Michael and I have subsequently adapted the approach as an alternative form of conference paper where we orchestrated a digitally-mediated excursion through the centre of Bremen. We have also more conventionally presented on this and similar methods, all of which combine digital technologies with urban exploration. See also: Exit the classroom! mobile learning and teaching Bremen: multimodality and mobile learning I’m in Odense today (8 Oct 2018) and am glad to be visiting the University of Southern Denmark as a guest of Nina Nørgaard and her colleagues in the Centre for Multimodal Communication. I have been talking about the relationship between multimodal assessment and feedback. These are my slides and references: Using multimodal artefacts created by students on the MSc in Digital Education, alongside my own experiences as a tutor, I argued that we should pay greater attention to the potential of multimodal feedback around assessment, for instance as a way of demonstrating the representational possibilities and academic validity of assignments crafted in multimodal form. Some of the ideas I talked about featured in my recent article in Multimodal Technologies and Interaction where I argued that multimodally-rich dialogue between teacher and learner can embolden students to be simultaneously adventurous, creative and scholarly in the assessment setting.

Considering the co-constituting nature of assessment and feedback it is surprising that there has been little critical interest in the relationship between multimodality and feedback, although work by Hung (2016) highlighted the potentialities of video feedback amongst students, while Campbell & Feldman (2017) are among those who have suggested that digital multimodal feedback might be an efficient way of engaging with large cohorts of learners. On previous occasions when I have had the opportunity to present my ideas to colleagues researching multimodality at University College London and University of Leeds I have come away with new ideas and ways of thinking about the subject. Today was no different. In the discussion that followed my presentation we talked about the way that multimodality often becomes confused with multimediality, and also what is potentially lost around what I'm going to call 'knowledge apprenticeship', when digital technologies are seen as a short cut to the acquisition of information and the production of multimodal artefacts. References

Today sees the first Learning and Teaching Conference here at Edinburgh University, which takes as its theme, 'inspiring learning'. For my part, I will be presenting a poster, Exit the classroom! Mobile Learning & Teaching, alongside my colleague from the Centre for Research in Digital Education, Michael Gallagher. The poster follows a path across six different excursions or exercises where, along with our colleague Jeremy Knox, we have explored the possibilities of mobile learning and methodology. Beginning with a two-day workshop that Michael delivered in Helsinki in 2013, through events in London, Amsterdam, Edinburgh and Bremen, our poster makes the case for taking teaching and learning beyond the boundaries of classroom and campus. The final and most recent activity in this series was a fully online event delivered earlier this year within the University’s Festival of Creative Learning, where our group brought together students, teachers, researchers and learning technologists from across three continents and a range of academic disciplines. In each case our excursion (or that undertaken by participants) was digitally-mediated as we drew on the capabilities of smartphones, instant messaging services and other networked content or applications. Having previously spoken and written about these exercises (including an article for Qualitative Research that should be available any time now), on this occasion I wanted to share our work in visual form. If you happen to be at the Learning and Teaching Conference and are interested in the work described here, Michael and I be standing next to the poster between 12.50 and 13.40. We're conveniently close to the refreshments so grab a coffee and Danish and come and say hello. Or you can view and download a pdf copy of the poster here: I am really glad to be delivering the opening key note presentation at today's Digital Assessment & Feedback: People, Places & Spaces conference at Lancaster University. I will be talking about Multimodality, Assessment and Feedback. These are the slides that I will be talking around: Although I have talked and written about multimodal assessment before, I am looking forward to arguing for greater attention towards the multimodal character of feedback and dialogue between student and tutor. When the teacher has an important role in encouraging students to recognise the scholarly validity of the digital multimodal form (Lea & Jones 2011), this can be achieved, I will argue, by presenting our comments, guidance or encouragement in corresponding form. Conversely, if our feedback is primarily conveyed through language (whether spoken or written) we implicitly defer to the power of words, while 'othering' alternative approaches as experimental or risky (and thereby less attractive in the high-stakes summative assessment setting).

Considering the intimate link between assessment and feedback, it is surprising that research investigating the relationship between multimodality and feedback is scarce (useful exceptions being work by Mathisen (2012) and Philips et al. (2016)). Plenty has been written about the possibilities and challenges of multimodal assessment however much less has been said about the way that, by taking a multimodal approach within their feedback, teachers can embolden and inspire students towards the representation of knowledge in ways that are simultaneously scholarly and in-tune with our increasingly digital and visually-mediated world. Thank you to Kathryn James and colleagues at Lancaster University for inviting me to speak at today's conference. References:

See also: Multimodality, assessment and language education Stories of transformative multimodal assessment Interweaving: multimodality, assessment and architecture

Later today I will be contributing to Making Research Visible, an event organised by the Research and Knowledge Exchange Office here at Edinburgh University. The aim behind the day is to explore the different ways that we can think about the accessibility and visibility of our research, for instance through social media. My input will be to talk about the process behind the video I created for the Manifesto for Teaching Online. I will argue that we can raise the profile of our work by presenting it visually. This is the video:

and here are the slides I will present this afternoon:

The portability of the video format, combined with the ability to convey a considerable about of content within a short space of time, allows us to extend the reach of our academic work, for instance through the sharing capacity of social media. In my presentation I will also describe how the medium provided an opportunity to match the representational form of the video with the following Manifesto statements, thereby enacting and advancing the same arguments:

Text has been troubled: many modes matter in representing academic knowledge

Remixing digital content redefines authorship

Arguing for the value of visually-mediated research does not mean dispensing with more conventional printed ways of sharing our research. Neither does it mean that the visual form will always be an appropriate way of sharing academic knowledge. All the same, in our increasingly networked and visually-mediated world, the video format is increasingly in-tune with increasingly multimodal literacy practices and representations of academic knowledge.

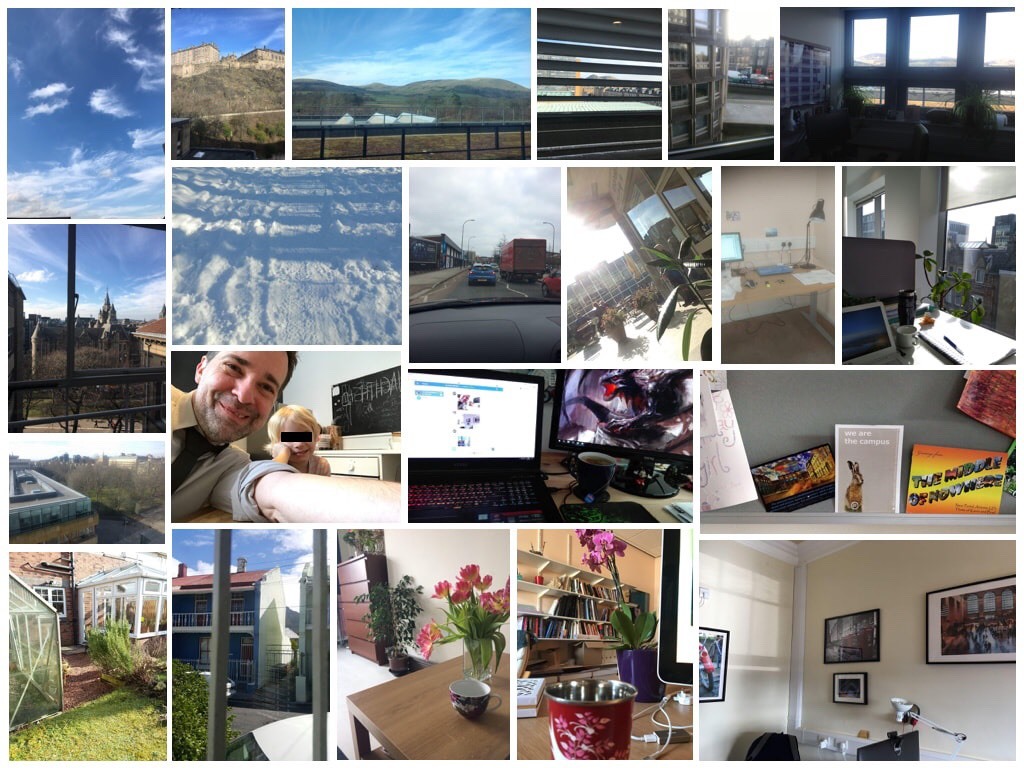

See also: Manifesto for teaching online: reaction! During our recent event, The Mobile Campus: Imagining The Future of Distributed and Digital Education at The University of Edinburgh, Michael Gallagher and I invited our group of 24 students, researchers, learning technologists and lecturers to simultaneously take a photograph of their surroundings. Through this elicitation of images we hoped to get a sense of the different types of 'learning spaces' being occupied across the group, which spanned several campuses and continents. Since the event, I have pulled the photographs together into a composite image: Click on the composite image to enlarge The images shown here could be analysed and then interpreted in a range of ways, however to start with I have attempted to group them under some broad themes: nature; institution; office; home; transit. Some of the photographs transcend these categories. It would also be easy to extend the number of themes.

Although the Mobile Campus event didn't set out to generate research data, it would still be interesting to subject the photographs to some kind of visual analysis. Thinking for instance about Gillian Rose's nine methods of visual analysis (2011), perhaps content analysis or a form of anthropological analysis might enable us to ask what the photographs tell us about the ways that the university is performed across a range of spaces and settings? Another line of inquiry would be to consider how the presence of overtly domestic spaces contrasts with the ways that online education is often (visually) portrayed as overtly sophisticated, clinical and high-tech. Looking across the images, plants outnumber computers while there is an even balance of 'homely' and 'officey' spaces. The snapshots offer an interesting glimpse into the different ways that the campus is performed and how teachers and learners engage with the university. Without making any claim to generalisability based upon images from a single event, it is tempting to consider whether this approach might help us to think about pedagogy and the nature of the university itself, as education becomes increasingly mobile and dispersed. References:

See also: The sonic spaces on online students What does Doctoral research look like? Away from the university |

Search categories

All

I am a Lecturer in Digital Education (Education Futures), within the Centre for Research in Digital Education at The University of Edinburgh.

@james858499 james.lamb@ed.ac.uk |