|

Earlier this year I completed my ESRC-funded PhD research which investigated the relationship between technology and the learning spaces of higher education. Prompted by a recent conversation among colleagues here at Edinburgh University about the potential of the digital dissertation, in this post I explain how my own thesis was presented in multimodal and digital form.

By ‘digital dissertation’, I am referring to the presentation of scholarship in overtly digital and multimodal form in those contexts where work is normally conveyed in a more essayistic and language-privileging format. At least in the arts, humanities and social sciences, it remains difficult to move beyond traditional print-based conventions within the high-stakes assessment setting. In the case of my own thesis, I sought to balance my desire to produce a richly multimodal and digital artefact, with University regulations and tacit disciplinary expectations around the exposition of knowledge. My wish to produce a digital dissertation came partly from my interest in multimodal assessment, as I have discussed in this journal article, this conference key note and other workshops with academic teachers. More important, though, was finding a representational format that would foreground the sonic and visual data around which much of my PhD was built. As I argue in the thesis itself, sound has tended to exist on the periphery of qualitative research (as discussed by Dicks et al. 2011) while the critical value of audio data has been undermined by a lack of consideration when reproducing sonic material alongside more conventional published researched (see in particular Feld & Brenneis 2004). The challenge I faced was to present audio and visual content in juxtaposition with written argumentation, while at the same time satisfying University regulations around the preparation of a traditional word-processed thesis. My response was to insert QR codes that linked to different types of digital artefacts. As I explained to the reader in the opening pages of my thesis, the intention here was that they could use a smartphone to access digital material alongside the printed content. True to one of the key ideas of multimodality, argumentation was made through the simultaneous juxtaposition of semiotic material, for instance words, images and sounds.

Therefore where my research involved the use of playlists as ethnographic artefacts, the reader was able to sample the nominated songs alongside my discussion of insights they had provoked into the way that learners used music to negotiate different types of learning spaces. These playlists – one for each of the American History and Architectural Design courses that provided the setting for my research - were hosted on the music-sharing platform Mixcloud. Here is the playlist I created with Architecture students:

Meanwhile in order to convey the sonic character of different teaching spaces, I created interactive sounds maps in Thinglink that situated ambient audio recordings and photographs against corresponding locations within diagrammatic floor plans. Here is the sound map for the area of the design studio where much of my field work took place:

Across more than a year of ethnographic field work I generated several hundred audio recording and thousands of photographs, some of which formed the basis of 15 short videos. Each video combined audio recordings, photographs and excerpts drawn either from my written field notes or from interviews. The following video captures the sights and sound of the architecture studio:

The creation of these different digital artefacts, combined with the way that they could be access via QR code, goes some way to showing how even within the constraints of producing a printed dissertation, it is possible to craft an artefact in digital, multimodal form. An important influence on my approach here was Kress’ work around aptness of mode (2005), the premise of which is that the digital form allows us to consider how we might shape the representational form of a digital artefact in a way that helps to best present the knowledge that is to be communicated. This meant producing a digital, multimodal thesis not for the purpose of experimentation, but rather because it was the most suitable way of executing arguments around the relationship between sound and physical space.

There are sure to be other and more imaginative examples of what a digital thesis can look and sound like, particularly when they emerge from the creative disciplines or within interdisciplinary contexts. And while my use of QR codes (rather than embedded content) may have been a neat concession to University regulations, it does feel like a compromise rather than a true use of the digital form. Nevertheless, I hope that my approach helps to stimulate more conversation about what is possible when it comes to producing richly digital and multimodal scholarship in an assessment setting, perhaps even contributing to conditions that are more conducive to this kind of work. References

1 Comment

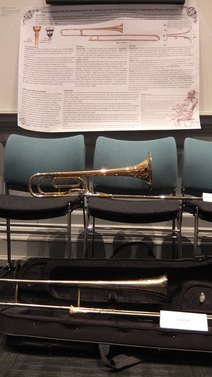

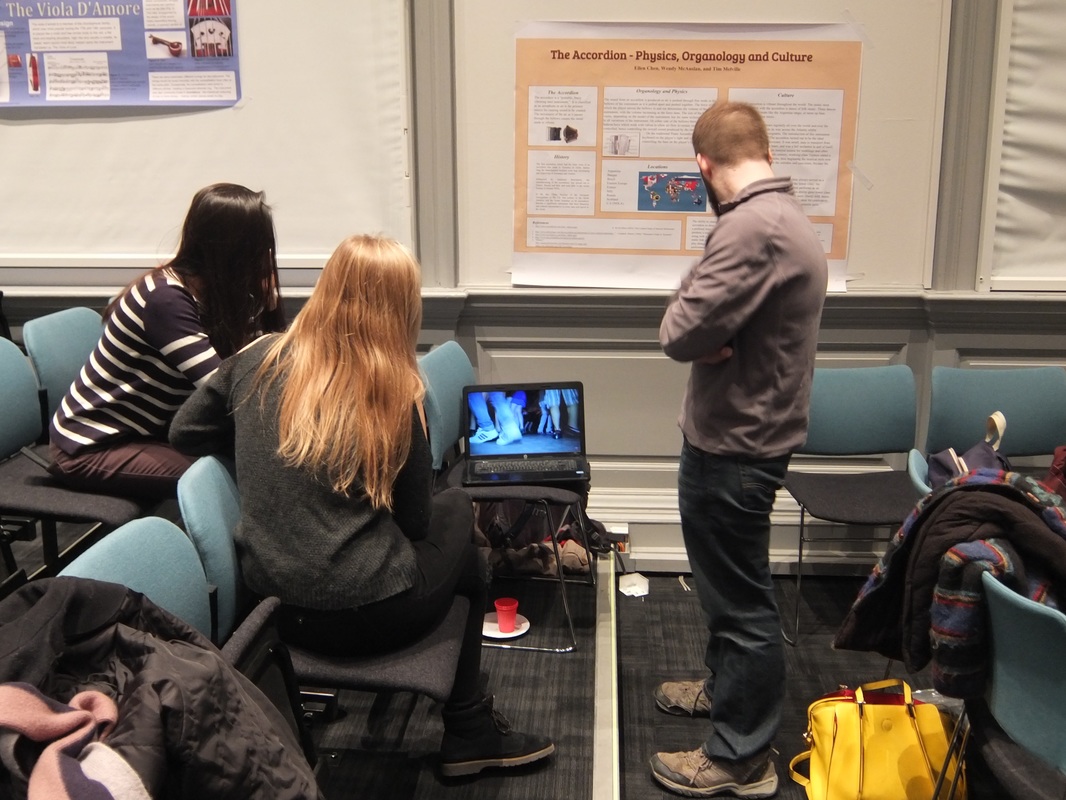

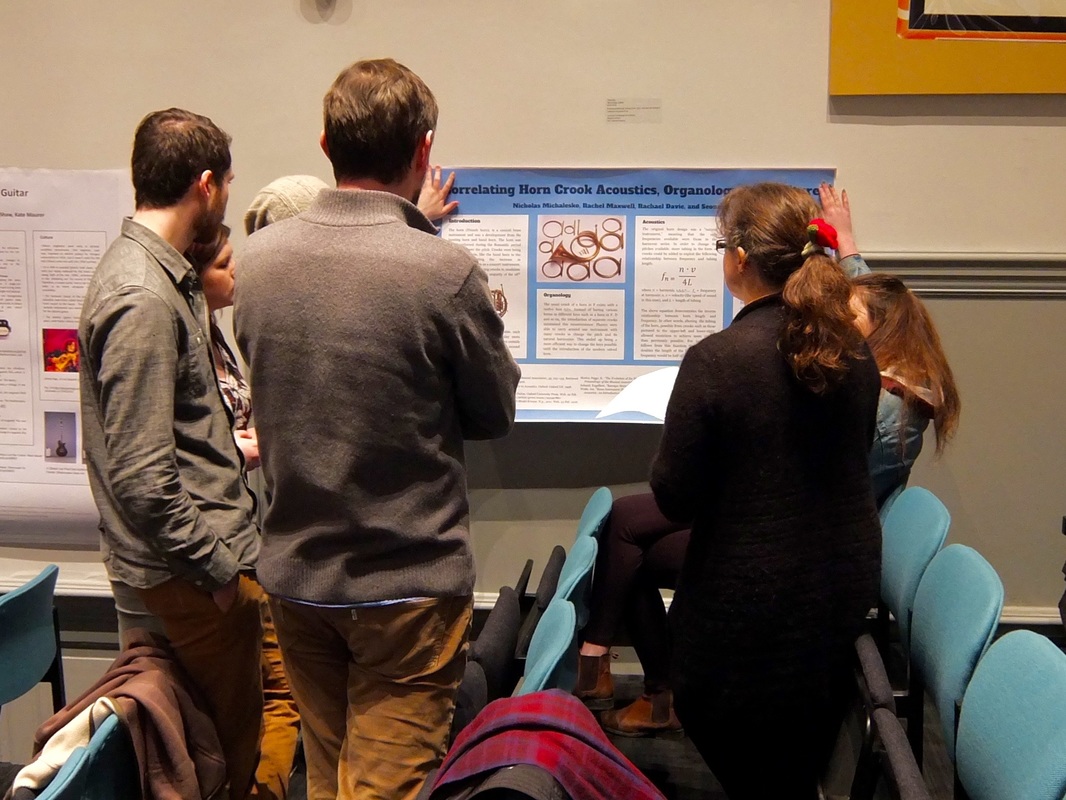

I spent yesterday evening at the Edinburgh College of Art, observing students from Edinburgh University’s MA (Hons) Music, as they participated in a poster assessment exercise. The invitation followed a recent interview-over-coffee with Dr Tom Wagner where he generously spent an hour talking enthusiastically about the innovative and evolving nature of assessment on the Music programme. The MA (Hons) Music was originally of interest to me as it’s a degree programme that is simultaneously situated in both the Humanities and what we might describe as the ‘creative disciplines’. The short video on this page neatly describes the distinct nature of the programme. The poster presentation assessment exercise challenged students to work together as they sought to investigate and then present the technical, historical and cultural significance of an instrument on their choice. I now have a greater appreciation of the accordion, hammond organ and Les Paul guitar, although no greater talent for putting any of these fine instruments to good use. The exercise is worth a 40% of the final mark for this particular course so its clear that this falls into the category of high stakes assessment. In an e-mail conversation earlier in the day Tom had revealed a mixture of enthusiasm and anxiety for this first-outing-as-an-assessment exercise and he repeated the “Fingers crossed it works!” mantra when we spoke at the beginning of the evening. My interest was in studying the different ways that students used the poster (and to a lesser extent its presentation) as a way of constructing and conveying meaning. At the same time I was keen to learn how they felt about the experience of putting together a multimodal artefact that drew on a range of resources, including and beyond language. With Tom’s permission I observed and spoke to students before, during and after the presentation of their work. I also took photographs of the posters and the wider class activity (again with permission of staff and the students concerned). Every poster featured a combination of words and images, most commonly pictures of instruments but also what I understood to feature soundwaves and other technical information. Other visual elements included an attention to the use of colour, background and typeface. The posters varied in the extent to which they moved away from what we might think of as the ‘essayistic’ conventions of linearity and a privileging of language. In every instance, printed text featured heavily and there was often a suggested path for me to follow through the poster (and on one occasion a series of arrows in order that I didn’t lose my way). This reminds of research by Lea and Jones (2011) into the practices of students at three UK universities where they found a reluctance to stray far from conventional ways of sharing knowledge. It also echoed the study by McKenna and McAvinia (2011) which pointed to a persistent attachment to linearity amongst students, even when presented we new, digital, creative ways of conveying meaning. This is simply an observation of the posters, not a criticism: indeed, the different groups may have felt that the most effective way of conveying their ideas was to transpose conventional language-based approaches onto the PowerPoint canvas. There were however examples of work where clearer acts of design were on show, for instance where motifs framed the page, or where text was laid over an image of a performing musician. On other occasions the poster itself was placed in juxtaposition with a separate object: a book of organ music sitting on a chair; a selection of trombones laid out parallel to the poster; a laptop with a looping video, which had seen Michael “basically spending about an hour and a half looking for examples of different type of accordion music” in order to show to tutors the variety of ways that the instrument was used. This final example is interesting in that of all the posters I studied, this was the only where the presentation would be accompanied by music. This makes me think of Gunther Kress’s work around aptness of mode (2005) where he proposes that multimodality enables us to consider the particular range of resources that might best convey intended meaning: a poster presentation about the accordion, featuring an accompanying accordion soundtrack, would be seem to be a very effective enactment of this principle. The presentation of the posters meanwhile made use of spoken language, voice, eye contact, gesture and other modes. Perhaps reflecting the high-stakes and unfamiliar nature of the exercise, most students were fairly rigid as they presented their work and arguments to tutors. An alternative explanation is that the layout of the lecture theatre rarely left much room to make use of expressive gesture to support the presentation of ideas. When they weren’t setting up or presenting their posters, many students took the opportunity to look at the work put together by other groups. Unprompted, clusters formed where students gathered to put questions to the authors of the different work. Reflecting on this, Peter described to me how he had “learned lots of new things about different instruments tonight” while a number of students remarked on how impressed they had been with the level of work displayed around the room. “Everything looks really good” Charlotte remarked, while Maria added “Loads of work has gone into this”. There was something really nice about the willingness of students to look beyond their own work: there was a sense of collaborative learning as students constructed a broader knowledge and understanding of their subject from the range of posters and approaches around the room. I was also interested to hear whether the students had any prior experience of putting poster presentations together. Although Karen described “doing this kind of thing in high school”, for the most part the poster exercise was a new approach for almost every member of the class. The exceptions were two self-described ‘visiting students’, who told me that this type of approach had been a feature in their studies in the US. In particular, Carl described his academic background in technical engineering where it was commonplace to use posters as a way of helping to explain potentially complex ideas to an audience. I was also interested to learn how students had found the wider experience of the exercise. Claire’s immediate response, delivered through a mixture of relief and laughter was that “I'm just glad it's not an essay!” which was met with the approval from the rest of her group. This was a feeling that would surface repeatedly in discussion, although two students pointed out that while it worked well in this type of assignment task, “an essay would be better suited on other occasions” (Mark). When pushed on this, Sarah explained “Well, I liked working on the poster as part of a group, but all the decisions you have to make - I’m not sure I would feel so confident doing it on my own”. When asked whether they would like to take this approach in the future, many students were enthusiastic about the poster approach however others suggested that the essay continued to be attractive as it didn't force them to make so many decisions about the form of their work. It was very clear that students had really enjoyed the exercise, and this was the position taken even by those who were nervously awaiting their turn to present the poster to their tutors. It is difficult however to unpick how their enthusiasm for the assignment was attributable to the form of the exercise (presented as a poster), the subject matter (selecting and studying an subject of interest to them) or whether it was the opportunity to work collaboratively. What come through very loudly amongst several groups was how they had enjoyed learning from the drawing on the different interests and talents of fellow group members. This was a point neatly captured by Jimmy who told me “I have an interest in playing guitar, Nico is interested in the technical side and Annie knows about the social side”. Without setting out to critique this exercise, perhaps one of the benefits that it brings (against the preparation of an essay, which one groups told me had been the original intended format for the assignment) is that the presentation element enabled students to describe the critical decisions that had shaped their approach. Tutors were offered insights into the methodology behind the poster they were examining, potentially offering a clearer appreciation of the learning that had taken place. This attention to the process behind the work, as well as the final artefact itself, features prominently in the research literature surrounding multimodality and assessment (for instance in the studies by Breeze (2011), Pandya (2012) and Wyatt-Smith Kimber (2009)) whilst the type of reflection being encouraged and shared by students would seem to echo the how multimodal artefacts can be valuably accompanied by the completion of a reflective essay (see for example by Adsanatham (2012), Barton and Ryan (2014) and Coleman, (2012). Drawing my thought here to a close, what I saw last night was an assessment exercise that had clearly excited students, whilst at the same time challenging them to construct and convey their ideas in new ways. Rather than working in ‘isolation’ on an essay (a situation a number of the students attested to), they had been challenged to work and learn collaboratively. At the same they had been forced out of their comfort zone of music composition and performance, and beyond the familiarity of the written form, to demonstrate understanding through an orchestration of semiotic resources, which required them to undertake acts of design. If student engagement is a vital measure of learning, in an environment driven by outcomes, benchmarking and performativity, importance is also placed on quantifying student progress and understanding. Or to put it another way, the success of this approach will also be measured by asking ‘How did the students do?’ Maybe if I promise Tom another coffee he’ll tell me how he and his colleagues felt about the quality of the poster presentations I enjoyed watching yesterday evening. With thanks to Dr Tom Wagner for his kind invitation to attend and to the students who took time to speak to me and allowed me to photograph their work. I have use pseudonyms in place of the real names of students cited above. References

ADSANATHAM, C. 2012. Integrating Assessment and Instruction: Using Student-Generated Grading Criteria to Evaluate Multimodal Digital Projects. Computers and Composition, 29, 152-174. BARTON, G. & RYAN, M. 2013. Multimodal approaches to reflective teaching and assessment in higher education. Higher Education Research & Development, 33, 409-424. BREEZE, N. 2011. Multimodality: an illuminating approach to unravelling the complexities of composing with ICT? Music Education Research, 13, 389-405. COLEMAN, L. 2012. Incorporating the notion of recontextualisation in academic literacies research: the case of a South African vocational web design and development course. Higher Education Research & Development, 31, 325-338. KRESS, G. 2005. Gains and losses: New forms of texts, knowledge, and learning. Computers and Composition, 22, 5-22. LEA, M. R. & JONES, S. 2011. Digital literacies in higher education: exploring textual and technological practice. Studies in Higher Education, 36, 377-393. McKENNA, C & McAVINIA, C. 2011. Difference and disconuity - making meaning through hypertexts. In Digital Difference: Perspectives on Online Learning. Land, R. and Bayne, S. (Eds) (Rotterdam, Sense Publishers): pp 45-60. PANDYA, J. Z. 2012. Upacking Pandora's Box: Issues in the assessment of English in Learners' Literacy Skills Development in Multimodal Classroom. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 56, 181-185. WYATT-SMITH, C. & KIMBER, K. 2009. Working multimodality: Challenges for assessment. English Teaching: Practice and Critique, 8, 70-90.

I spent an hour flicking through boxes of records in the charity shops of Edinburgh's Clerk Street. I was searching for some festive cheer. Here are the highlights of what I found. It's the perfect soundtrack to a mediocre Christmas party. Or the ideal gift for a distant relative who doesn't really care for music.

Actually, that's not fair: there are some nice songs here, after a few listens. I particularly 'Julekort' by Randi Brandt Gundersen (Track 1) and while I don't speak Norwegian I imagine it's about log cabins and good-looking people in NorthFace jackets. Meanwhile I can follow the Christmas message in 'Je ne Crois plus au Pere Noel' by Nina & Frederik (Track 4) however I know that children read this blog so I won't reproduce a translation here. 'Villanico' by The Harry Simeone Choir (Track 3) could be from an Ennio Morricone soundtrack to a Sergio Leone film (Once Upon A Time in A Manger?). The remaining songs emerged from my stand-off with the 'Country & Western Christmas' compilations that seemed to be herded together in the crates of discounted vinyl of Edinburgh's southside.

1. Julekort by Randi Brandt Gundersen 2. Santa and the kids by Charley Pride 3. Villanico by The Harry Simeone Choir 4. Je ne Crois plus au Pere Noel by Nina & Frederik 5. Pretty Paper by Willie Nelson 6. Jolly Old St Nicholas by Chet Atkins Happy listening and Merry Christmas! James

Noise carries its own meaning in different disciplines. It can be psychological, physical, technical, cultural. It accounts for different phenomena within semantics than in communication studies and serves a different purpose again within corners of education research. It variously concerns disruption, distraction and bias.

Right now, noise refers to the sound of machines attacking asphalt within close proximity of PhD Suite (Room 1.10) in the School of Education. The building of subject knowledge is locked in battle with the sound of tarmac being deconstructed. I find myself typing in stop-start rhythm to the sound of steel on concrete, which is fine for some scholarly tasks but not for others. Better than no typing at all. In response, I’ve created a playlist for occasions where composition and contemplation doesn’t lend itself to an industrial soundtrack: anti-noise to aid my concentration.

The playlist is intentionally lyric free, even if there are occasional fragments of dialogue and voice: the reading list in front of me is complex and lengthy enough without the need for additional words to contend with. I realise on playback that, without it being my intention, there’s a clear machine-like quality to some of the tracks here, most notably Arab Strap’s The Bonny Barmaids of Dundee.

Once the building work is complete our office will face onto a courtyard where students and staff will be able to congregate, relax and discuss the matters of the day. This will create its own soundtrack, which may or may not be conducive to the writing and reading that lies in store. When the sound of conversation and laughter penetrates PhD Suite (Room 1.10), I wonder whether I might long for the predictable ambient pattern of excavators attacking paving slabs. Noise carries its own meaning in different disciplines, but it’s also contingent on the activities being attempted within the space and time that it shares. James Lamb is a PhD student within the School of Education (Room 1.10) at the University of Edinburgh. This post also appears on the website of the Elektroniches Lernen Muzik. See also: Old School Maps, music and augmented reality Surf guitar or The unrehearsed imagination of school

The Manifesto for Teaching Online was conceived in 2011 by my colleagues within the Digital Education group at the University of Edinburgh. It set out to articulate a position - and provoke discussion - surrounding online education. My contribution to the original Manifesto was the preparation of a short home-made video that offered a visual representation of the twenty statements. I revisited and revised the video in 2013 with a closer attention to how the images could align with the messages that I felt the Manifesto was trying to convey.

Four years down the line I've been very glad to participate in the reconsideration and reconfiguration of a 2015 version of the Manifesto for Teaching Online. The notion of the remix features prominently - loudly! - in this new Manifesto.

Remixing digital content redefines authorship

One of the things that I like about the Manifesto is its intention to prompt discussion rather than dictate a set of hard-and-fast rules: we are encouraged to approach and interpret the statements in our own way. My own take on the 'Remixing' statement is as follows. The increasingly vast and varied amount of digitally-mediated content enables us to construct knowledge in new and exciting ways. At the same time we have access to a growing array of devices and other technologies that allow us to convey or re-shape what we draw from the growing body of digital content. This in turn pushes us to rethink what we understand by 'authorship' and 'composition' of scholarly work. To illustrate my point in a very basic way I've created this (very basic) animation:

Returning to my interpretation of the 'Remix' Manifesto statement, the digital content that I drew on within the animation features audio taken from two web-hosted video clips. This includes a seminar discussion on the subject of the 'digital city' featuring Mathias Fuchs from Leuphana University. I also introduced the voice of Kathleen Fitzpatrick, taken from a lecture she delivered on the subject of digital authorship, at Duke University. The music track is 'Scratched' by Etienne De Crecy (no explanation required). Listen carefully and you'll also hear the sound of needle static, previously downloaded from a sound effects archive and unearthed from my iTunes folder. The digital devices and technologies that I used to put the animation together meanwhile included my computer, an iPhone for the lazy recording of sound from the video clips, and then software in the form of PowerPoint, Photoshop and SoundStudio.

Perhaps more interesting than the animation itself is the questions that it asks about the way that the scholarly remix problematises conventional understandings of composition and authorship. For instance, how much of the animation is really my work? If there's any merit in the animation, how much of it is attributable to the technology? Is it ethical for me to have taken Mathias Fuchs' voice out of context? How would Kathleen Fitzpatrick feel about my manipulation of her voice with extra reverb? And, as Fitzpatrick points out herself (2011), how does this type of 'mash up' sit within existing guidelines surrounding plagiarism? In keeping with the ethos of the Manifesto, with an eye to encouraging reflection I won't try to answer the questions that I've drawn attention to here. I'll include some references though, just to be on the safe side.

De Crecy, E. (2000) Scratched. Tempovision [CD]. Paris. Disques Solid.

Fitzpatrick, K. (2011). The digital future of authorship: rethinking originality. www.culturemachine.net. 12: pp.1-26. 'Kathleen Fitzpatrick: "The Future of Authorship: Writing in the Digital Age"'(2011) YouTube video, added by FranklinCenterAtDuke [Online]. Available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v4qq01Qskv0 (Accessed 24 October 2015) 'Mathias Fuchs - Remixing Digital Cities' [video] (2013) Transmedia.de. Available at at http://www.transmediale.de/content/presentation-mathias-fuchs-remixing-digital-cities (Accessed 24 October 2015)

Elektronisches Lernen Muzik is a project which explores how music accompanies and inspires scholarly work. It emerged from conversations between Michael Sean Gallagher, Jeremy Knox and myself whilst taking a course in E-Learning and Digital Cultures, part of the MSc in Digital Education at the University of Edinburgh. We were struck by how important the conscious use of music was in supporting our engagement with the E-Learning and Digital Cultures course as we reflected on ideas in the literature, constructed knowledge and explored ways of representing our ideas. Going further, at different times we found ourselves drawing on the same musical genres and artists - in particular Brian Eno and Kraftwerk - as we thought about issues surrounding posthumanism, digital authorship and other course themes.

For the most part Elektronisches Lernen Muzik has focused on inviting students, tutors and others with an involvement in educational activity to compile and then share the playlists that accompany and inspire their scholarly work. In each case, the creator is required to prepare 'liner notes' explaining how the tracks support his or her academic activity, alongside an original image or photograph to represent the 'cover artwork'. The playlist is then made openly available via our project site in order that any interested parties can draw on it to support their own work. Through the project we've now shared 16 playlists, the most recent of which gathers together Old Skool hip hop that I listened to as a high school student and then continuing into my time as an undergraduate. You can listen to the playlist below or see the full details (including liner notes and cover artwork) on this blog entry from the Elektronisches Lernen Muzik website.

If you'd like to contribute a study playlist I'd love to hear from you. E-mail me at [email protected] and we can talk about what's involved (although alas, this doesn't include royalties or an advance).

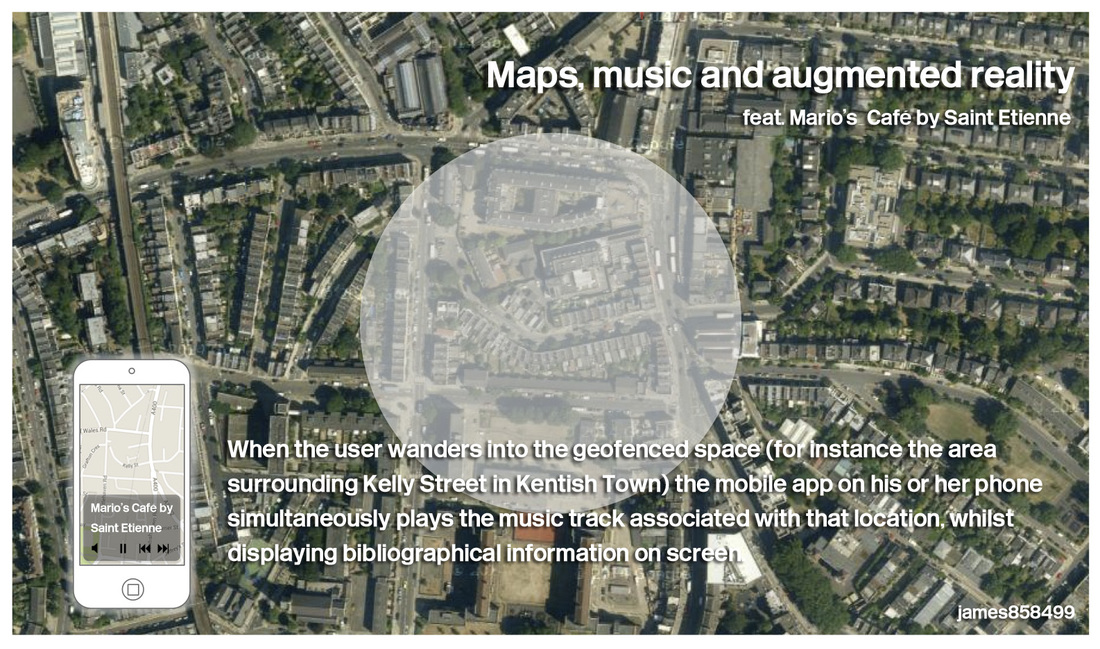

I've been wondering what it would be like to wander through a city - London, most likely - listening to a playlist that's linked to the places you encounter. I think it might offer an interesting way of telling stories about the city, in the same way that you might read a book or watch a film or documentary. I suppose the difference here is that you would be closer, geographically at least, to the places where different events took place. And I wonder whether this might be achieved through a mobile app that provides some form of musically augmented reality? Although augmented reality is normally used to describe the technological manipulation of a visual plane, I'm tuning into the idea that it is concerned with any of the senses and am focusing on sound - or music, more specifically - to enhance and change our perception of what is around us. Here's how it might work. Within a dedicated urban space, individual songs would be attached to specific places and spaces: a street, a park, a pub, and so on. These songs would then be geofenced on a sound map, which would be accessed by the mobile app. This would be activated when the user enters that (real life) location. There would probably be satellites, code and other things like that involved. Here's what might happen in practice. You put on your trainers. You plug in your earphones, maybe setting the volume so that you can still hear a trace your surroundings. You activate the Location function within the settings on your mobile. You open the app. You take a left into Kelly Street in Kentish Town and the app automatically begins to play a song. You look down at your mobile and the app tells you that it's Mario's Cafe by Saint Etienne. A short description explains the song's relationship with the street you're walking. You ignore the details for the moment, step out of the rain and enjoy your musically-augmented reality, with a cup of tea and a bun. In order for this to work, I think each of the songs would need to tell a story about the particular part of the city to which is it geolocated. All of these songs, for instance, paint a rich and colourful picture about different places, whether in the past or present: White City by The Pogues, Sunny Goodge Street by Donovan, Victoria Gardens (and plenty of others) by Madness, Denmark Street by The Kinks, just for starters. I'm waiting for the call to start work on the'Saint Etienne's London' app.

Each autumn I spend time a fair bit of time in local high schools, meeting with prospective higher education students as they make plans for college or university. Over and above the pleasure and satisfaction that comes from meeting and helping talented young people, these visits often present interesting and entertaining insights into everyday school life. These glimpses go beyond (or contradict) the sometimes constructed picture of school that we see in drama, documentary and news features. I don’t think that the unrehearsed humour and imagination of school-life is always told in the more considered representations of what goes on inside and outside class.

To make the point, I’m going to share an audio clip I captured earlier this year whilst meeting students in school. The allocated interview room on the day in question was located within the music department which inevitably meant that my occasionally wise words of guidance were continually accompanied and disrupted by what I presumed were rehearsals for a forthcoming school show. Which isn’t to say that every interruption was unwelcome: on the contrary, I couldn't resist using my iPhone to record the following track which seemed somehow out of place within the day's wider soundtrack:

Dick Dale’s 1962 surf classic Misirlou, played out-of-key and on-the-xylophone: as I said, the unrehearsed humour and imagination of school-life. I would be thrilled to find that the choice of material was less to do with the use of Misirlou as the title track for Quentin Tarantino's Pulp Fiction, than Surf Rock featuring as a part of the Higher Music curriculum: “OK class, today we’ll be studying wet string reverb so I hope nobody has forgotten to bring their Fender Stratocaster?”

The audio clip captures my journey around the music department as I attempted to track down the source of this inventive mallet-rock. I stopped short however of intruding upon the practice space, which unfortunately means I can’t give credit to the musicians responsible. Nevertheless, I’m sure the audience at the school show would, like me, have been stoked.

Here's an interesting Wikipedia history of Misirlou as well as the 1962 version recorded by Dick Dale and the Del-Tones, below.

Earlier this week I received an email exotically entitled 'Bangkok kitchen'. The sender was my friend Paul who is living and working in Bangkok. It featured a photo of his kitchen. Domestic and exotic. The image featured a can of Leo beer ('Smooth and great taste'), alongside a home-made CD compilation that I put together away back in 2001. At that time there were a couple of club nights in Edinburgh with a playlist which might be described as a delicious cocktail of easy listening, exotica and lounge. From recollection, the CD pictured in Paul's debonair kitchenette included the songs that featured in those sophisticated nights at the Assembly Rooms, ABC Cinema and similarly lustrous venues.

Easy listening probably isn't the most sophisticated or significant chapter in the the story of popular music, however there's more to it than comfortable knitwear and safari suits. This, after all, is a genre that encompasses lounge, soundtracks and the strange world of Exotica. In Easy! The Lexicon of Lounge (Dylan Jones, 1997), RJ Smith describes exotica as 'a round-trip departing everyday for something more fabulous. It had the feel of distant places, but it took you to spots never before trekked by man'.

And so within a couple of days of receiving Paul's email I'm able to reply with this digital, cloud-based compilation that variously visits the Caribbean (Harry Belafonte, Monty Norman), Latin America (Astrud Gilberto, Walter Wanderley), Ye-Ye Paris (Serge Gainsbourg, Jacques Dutronc, Brigitte Bardot) and other far flung destinations. And through the power of digital technology, I'm also transported back to that exotic time and place that was turn of the century Edinburgh.

|

Search categories

All

I am a Lecturer in Digital Education (Education Futures), within the Centre for Research in Digital Education at The University of Edinburgh.

@james858499 [email protected] |