|

I have been a little slow to share this article, published in Qualitative Research at the end of 2018, that I wrote with my colleagues Michael Gallagher and Jeremy Knox. It reports on a methodological exercise we took in London where we brought together ethnography, multimodality and urban walking. This involved making an unscripted walk through central London that we attempted to document through photographs and field recordings. This video goes some way to capturing what we did.

In the moments after drawing our excursion to a close, Michael, Jeremy and I began working through the data, generating some ideas that we presented at a conference the next morning (and we discuss in our article). This includes the potentialities of combining urban walking and ethnography, but also the limitations in our attempt to generate data as a way of reflecting on our relationship with the city.

Since undertaking that first exercise in London, Michael and I have subsequently adapted the approach as an alternative form of conference paper where we orchestrated a digitally-mediated excursion through the centre of Bremen. We have also more conventionally presented on this and similar methods, all of which combine digital technologies with urban exploration. See also: Exit the classroom! mobile learning and teaching Bremen: multimodality and mobile learning

0 Comments

Sound, including the practices of listening and production, have been used in a range of ways to ask questions around community, culture, power and other aspects of our social world. Researchers have turned a critical ear to the sonic environment in order to understand how sound can be used to construct personal space (Flügge 2011), exercise control and enact power in the hospital ward (Rice 2003) improve workplace efficiency (Bijsterveld 2012) and beyond. Elsewhere, reflecting the relationship between emergent technologies and the recording and reproduction of sound, Bull has studied rituals around the iPod (Bull 2005), Sterne makes the case for the MP3 as a cultural artefact (2006) and Prior has recently written about the complex hybrid of human-and-machine in the vocal assemblages of popular music (2017). These examples point to the growing recognition that sound has an important role to play in contemporary research, thus beginning to address what Bauer, writing almost two decades ago, saw as the absence of adequate methodology or mass of research to exploit the critical potential of sound within social inquiry (2000). These contemporary research-adventures-in-sound have started, in a small way, to challenge what Daza & Gershon describe as the ‘ocular hegemony’ of inquiry, through its devotion to the visual, to speech and to text (2015: 640). A survey of the literature concerned with sound in social settings describes research under the banners of acoustemology, acoustigraphy, acoustic ecology, anthropology of sound, ethnomusicology, pyschoacoustics, sonic cartography, sonic ethnography, sound studies and beyond. Considering the breadth of critical work that begins with sound, alongside the potential for these activities to ask questions around comprehension and epistemology, human relations and hierarchy, it is surprising to find that sonic phenomena and practices have rarely featured within education research. A rare voice in this respect is Walter Gershon who, in making the case for sound as educational systems (2011), questions the ‘scant study of sound in educational contexts either in or out of schools, other than as a distraction to learning.’ (2011: 67). In contrast, Gershon has used what he describes as ‘sonic cartography’ to explore ideas of race and place within the urban school classroom (2003) and more generally argues that an attention to the sociocultural character of sound provides us with insights into the construction of values in educational settings and the nature of meaning itself (2011). My own education research (investigating meaning-making around assessment) hears Gershon’s call for greater attention to sound as a means of inquiry around learning. Alongside the collection of field recordings in and around the classroom, I have collaborated with students in the creation of music playlists that accompany or inspire their work, and am gradually piecing together an interactive sound map that reflects how epistemology is enacted in the American History and Architectural Design courses that represent my field sites. More recently I have been thinking about whether I can produce sonic artefacts as a way of communicating some of the rituals and meaning-making practices that I have heard, seen and been told about within the dominant learning spaces of these two courses. Rather than simply writing about my experiences (with the associated problems of translating sounds into words) or re-playing recordings, I have been selecting and repackaging this sonic material, considered in the light of my wider research, in order to make arguments about the nature of meaning-making in different educational setting. There is a precedent for this approach - what we might call the critical manipulation of sonic research material - in Steven Feld’s influential work around acoustemology where he proposes a ‘a union of acoustics and epistemology’ that seeks to ‘investigate the primacy of sound as a modality of knowing and being in the world’ (2003: 226). Rejecting the tendency within ethnography to view sound as supplementary to the serious business of writing-up in monograph-form, Feld produces, manipulates and then releases sound recordings as a way of asking questions and conveying the ‘sense of intimacy and spontaneity and contact between recordist and recorded, between listener and sounds.’ (Feld & Brenneis 2004: 465). The case for this approach is further made within sound studies by Bruyninckx where he adapts Latour’s (1986) belief in the immutability and mobility of inscriptions (1986) to argue that a scientific approach to working with sound should allow the researcher to ‘dominate’ sonic material through cutting-up, recombining and superimposing what was collected (2012:143). As long as the sound recording can never accurately reproduce what was heard in the field (see amongst others Gallagher 2016 and Sterne 2006), we should take advantage of this detachment, Bruyninckx suggests, to meaningfully re-work the gathered sonic material. There are echoes in this work of speculative methodology which encourages imaginative approaches to social research in order to account for the complex and open-ended nature of our lived world. The remixing and repackaging of sonic material resonates with the creative capacity of speculative research (Ross 2016) as well as its interest in nuance and the unhinged rituals of everyday life (Michael 2017) over reproducibility and generalisability that dominates social research. Furthermore, the digital reworking of recorded sonic content, with the purpose of exploring and explicating ideas through research material and activity, is in tune with Ross & Collier’s (2016) call for methods that reflect the increasingly digitally-mediated nature of society. Combining the interests of speculative research and sonic artefacts as method, I have produced a sonic artefact for each of the American History and Architectural Design courses, primarily drawing on the dominant teaching and learning spaces of each course. Working through my field recordings and field notes, and influenced by ideas that emerged from observing, interviewing and photographing students and tutors across two semesters, each artefact talks about the nature of meaning-making in the corresponding course. The selection, configuration and prominence of the different phenomena (explained in the short commentaries below) are my attempt to use sound to explore and convey ideas around hierarchy, materiality, epistemology and pedagogy that reflect the broader interests of my research. What the artefacts do not attempt is a complete or accurate recording of what takes place in each learning space: the possibility of producing this type of record is challenged by the way that we each hear what we want to hear (Augoyard & Torgue 2005), that sound alters in response to the shifting presence of human and non-human bodies within any setting (Gallagher 2016) and the manner in which devices for recording and re-playing sounds deconstruct, filter and then repackage what is heard in the moment (Sterne 2006). Sonic adventures in American History This artefact is made up almost entirely of sounds recorded in (and around) the two lecture theatres and tutorial rooms where teaching was delivered across two semesters. The only exception is a short piece of conversation from a tutor’s ‘office hours’ that took place in a cafe adjoining the History department. Human voice - and more specifically that of the four lecturers and their tutor colleague - dominate this artefact, reflecting how classroom pedagogy depended heavily on a predominantly one-way communication of Historical knowledge. We briefly hear students discussing course content and an upcoming coursework essay (within a tutorial exercise; during office hours) however for the most part the presence of students is audibly present through typing, coughing, shuffling of paper, shuffling into class, and so on. At other times we can vaguely make out the sound of informal chatter as students wait outside the lecture theatre ahead of the scheduled start time: this period of anticipation or hiatus reflects the highly structured nature of the American History course. That we can hear the sound of students producing notes using word processor software (the clicking of keyboards) and also by hand (the zip of a pencil case opening, a fresh page being torn out of an A4 pad) reflects the different approaches I heard and observed during class. The audible contrast between keyboard composition and the more conventional technologies of rollerball pen and refill pad point us towards the varying literacy and meaning-making practices with a body of learners who are often lazily assigned the status of being entirely devoted to digital interests and rituals. Beyond the varying digital literacy practices of students, this sonic artefact makes three suggestions about the nature of meaning-making within the American History class: the communication of a body of Historical knowledge; the hierarchical authority of the lecturer, and; the heavy privileging of language (spoken, written, typed). Sonic adventures in Architectural Design The artefact for Architectural Design comprises field recordings from the design studio, exhibition gallery, lecture theatre, print room, crit room and site visit. For the most part however, we hear sounds from the design studio, reflecting its dominance as the space where students and tutors would congregate, and where students for the most part preferred to work. The artefact also captures the conversational nature of teaching and learning: a group tutorial; a one-to-one discussion between student and tutor; a group of students sharing ideas and offering each other feedback. The conversation does veer away from the subject of Architectural Design, however, as we hear students making chatting informally, laughing and generally enacting a sense of social amiability. Returning to the design-work-in-hand, there is the sound of constructing knowledge through technology (typing instructions into design software), paper (the rustling of posters) and other physical materials (sanding a block of wood), thereby reflecting the varied ways that meaning is constructed and conveyed within Architectural Design. We briefly hear music, on this occasion played through laptop speakers but more typically through earphones, when students wanted to enter an ‘auditory bubble’ (Bull 2005: 344) that would exclude the competing actions and distractions of those around them. The pedagogical approach in the Architectural Design course also placed importance on students explaining their work to an audience of peers and tutors, through a multimodal orchestration of voice, gesture, models and visual work: this can be heard in the sound of students presenting their plans-in-progress. If these artefacts immediately lack the coherence or order of more conventional approaches to communicating scholarship, they should heard in the context of John Law’s work around mess in social research. The fluctuating and occasionally jarring assemblage of sounds surely reflects the untidy reality of our world (and educational practices and spaces). The awkward orchestration of academic content, coughing and construction work penetrating the classroom alerts us to the minutiae that, according to Fenwick et al. (2011) have so often been overlooked in educational research, where inquiry privileges what Fox & Alldred (2017) describe as a ‘what works’ agenda, driven by a desire for outcomes and learning gains, over the complex reality of what takes place within learning events. What the different artefacts do not offer is a complete representation of the meaning-making that takes place across the two courses, only the work which happens in the major teaching spaces. It became clear in conversation and interview, as well as in the ‘digital postcards’ they sent me, that beyond the learning activities represented above, students would write and read, design and research, in a diverse range of settings. Assuming it was possible to gain regular access to these often private and occasionally impromptu study spaces, an alternative and more extensive sonic exercise might seek to account for learning that took place in the cafe, jazz bar, bedroom, train, plane, street and other settings that students described. Taking the example of the American History class, an attention to activities beyond the classroom would reveal how students use the body of knowledge communicated by tutors, demonstrated during other parts of my research, including the days I spent shadowing students in the lead-up to an essay deadline. A further limitation of this approach is that while I think the artefacts feature almost everything significant that took place in the different teaching and learning settings, the use of PowerPoint technology in American History lectures, and the consumption of food and drink in the Architectural Design studio, which were prominent in the visual research material I collected, do not register in my sound recordings and therefore do not feature in the pieces presented here. Therefore where the case is made for sonic methods in social research, this perhaps need to exist in conjunction with an attention to other sensory material in order to recognise that ‘regardless of how they are conceptualized, the senses are utilized in concert with one another’ (Gershon 2011:78). In justifying my own approach, the creation of the sonic artefacts presented here has been shaped by what I wrote, photographed, read and was told, as well as what I heard around the lecture theatre, tutorial room, design studio and beyond. From design studio to lecture theatre Finally, as my research is undertaking a comparative analysis of meaning-making across the two courses, I produced a third artefact that brings the two sonic pieces together. Assigning the sounds of the Architectural Design course to the left audio channel and American History the right channel, aural attention shifts over the course of one minute. The unexpected value of this third artefact is that it emphasises the shifting level of formality and student voice between the Architectural Design and American History courses in a way that was less apparent when listening to the individual sound pieces in isolation. More generally, listening to the different courses without interruption emphasises the contrast between the calmness, order and structure of the learning that took place in the lecture theatre, with the more erratic and creative energy of the design studio. In this way the configuration of each sound clip broadly exposes the nature of meaning-making in the two courses, something I am writing about elsewhere. At the same time this artefact reminds us that there are qualities and rituals that transcend disciplinary boundaries: the sound of students at work persists across the combined artefact, even if differently represented through sound. Further, in each case the learning that takes place is interspersed or accompanied by interests and activities beyond the immediate purpose of the Architectural or Historical project: air conditioning, passing cars and chairs; social media notifications, shuffling feet and the slamming shut of desks at the end of class.

References:

See also: Speculative Research feat. Slick Rick Processing sound for research The sonic spaces of online students Earlier this afternoon I contributed to a Digital Transformation of Creative Industries conference here at Edinburgh University, which featured stellar presentations covering different aspects of digital culture and technology: sound, labour, heritage, journalism and beyond. Starting from the position that Architecture is one of the creative industries, I drew on my doctoral research to ask what we might learn from the richly multimodal, creative and inter-disciplinary approaches and conditions that exist around Architectural Design pedagogy. These are my slides: ...and this is an approximation of what I said:

Great to be a part of these conversations around the digital transformation of the creative industries.

Here are my slides from the Interweaving Conference at Edinburgh University earlier today (6 September 2017). I was presenting on the relationship between multimodality and assessment within increasingly digital learning environments and society more generally. The central argument of my research was that, contrary to the tendency within the literature to conceptualise multimodal assessment as being new, experimental or unconventional, this position might extend only as far as the boundaries of our own classrooms or disciplines.

The literature that takes a specific interest in multimodality and summative assessment is dominated by those researching or working within what we might describe as ‘language-based’ courses and contexts: primary education literacy, secondary-level English, higher education Humanities; composition classes within US colleges and universities. Presumably this is because these are the subjects and disciplines that are most unsettled by the growing propensity towards richly multimodal ways of constructing and communicating meaning, prompted by the growing presence of digital devices, learning spaces and pedagogies in higher education. Drawing on my ethnographic study of meaning-making around assessment within an undergraduate architecture programme, I argued that multimodal assessment could be supported by what we might see as firmly established examples of ‘best practice’ around assessment feedback. If this seems a far from ground-breaking observation, it is worth noting that in the considerable body of literature that investigates the relationship between multimodality and assessment, including instances that have examined the introduction of richly multimodal assignments in place of the essayistic form, there are scant references to highly cited work around assessment and feedback. Similarly, there are few examples of researchers, course designers or tutors looking to the work of academic colleagues who are already immersed in multimodal teaching, learning and assessment. The Interweaving Conference set out to bring together the broad range of research and researchers working in education at Edinburgh University. In line with the interdisciplinary interest of the conference, I concluded my presentation by suggesting that in those situations where we look to introduce richly multimodal assessment to accompany or augment existing essayistic approaches, we might wish to travel beyond the boundaries of own disciplines - and the walls of our classrooms - to look at interesting and firmly-established strategies around assessment and feedback. See also: Visual and Multimodal Forum at the UCL Knowledge Lab Assessment, feedback and multimodality in Architectural Design Architecture, multimodality and the ethnographic monograph Over the last year I have taken thousands of photographs whilst observing students and tutors from Edinburgh University's Architecture programme. At the beginning of this exercise I was mostly interested in recording what took place directly around assessment: preparing the portfolio, presenting work in a review exercise, practices around marking and moderation. Over time though I have sought to capture a broader range of phenomena as I have looked towards sociomateriality as the critical lens for my Doctoral research. From initially focusing on the meaning making rituals of students and tutors around assessment, I have instead been looking to the ways that knowledge construction in the Architecture studio is a more complex entanglement of human, technological and other material interests. Or as Fenwick and Landri describe in their work around sociomaterial assemblages in education:

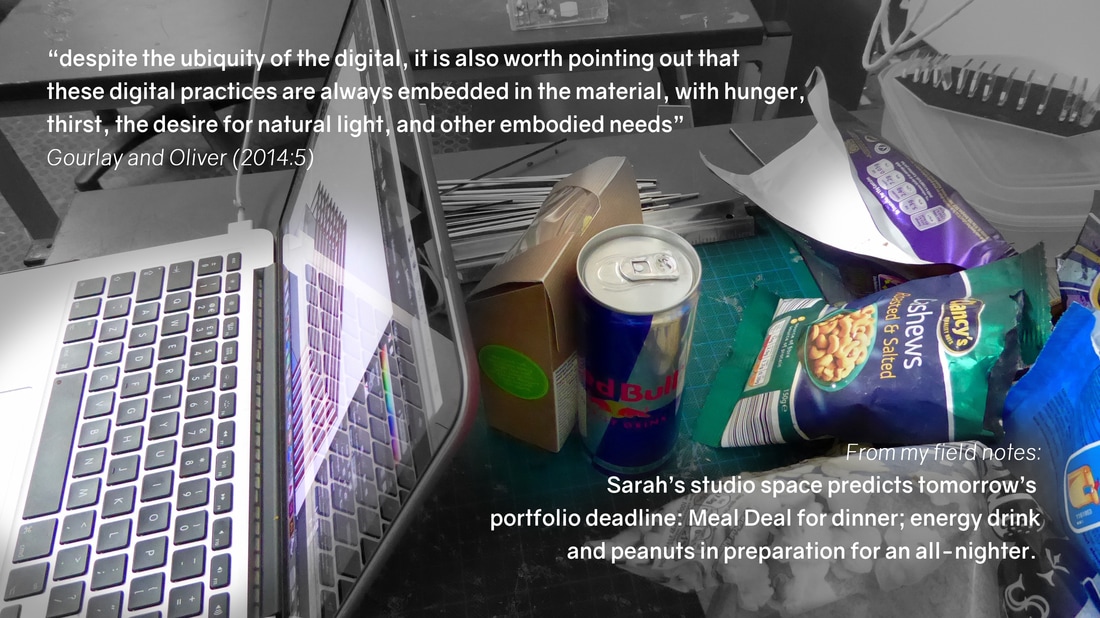

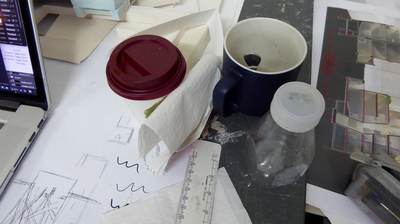

If I was initially guilty of viewing assessment in an overly simplistic way, as a fairly clear-cut exchange between student and tutor, sociomaterial critiques of education have instead encouraged me to examine the messy reality of what takes in and around the classroom, where 'learning is embedded in action and emerges through practice, processes that produce the objects and characteristics of educational events.’ (Knox and Bayne 2013). In this way assessment can be seen as a performance that depends on the student and tutor, but also looks to the role of curriculum, technology, sound, light, clothing and other visible and invisible actors within an evolving pattern of materiality (Fenwick et al 2011:8). What this has meant in practice is that, as well as continuing to photograph students and tutors in the Architecture studio, I have pointed my camera down at the floor and upwards to the ceiling. I have crawled under desks and balanced on chairs. I have photographed and recorded the sounds of ventilation shafts, data projectors, corridor conversation. I have attracted troubled glances from students unfamiliar with my research. Without having yet commenced my analysis of the gathered data, a recurring theme to emerge from my photographs and also my written field notes, is the way that food and drink seem to be an integral part of what takes place in the studio. Alongside the more recognisable tools of the architecture student we find snacks: pencils next to a packet of peanuts; chocolate alongside cardboard; Rhino with Red Bull. click on image to enlarge Through the image above I have tried to show how my field notes and photographs resonate with some of the principle ideas around sociomateriality within education, in this case echoing work by Gourlay and Oliver (2014) where they offer a sociomaterial account of digital literacy practices:

For the purpose of further illustration I have included below a small selection images which would seem to reiterate Gourlay and Oliver's call to remain alert to the way that our use of digital resources in education, for instance around assessment, is always and inevitably entangled with a much broader range of resources, influences, limitations and opportunities beyond the interests of the assignment task. click on images to enlarge References

See also: Digital sociomaterial journaling Camera, recorder, scissors, brush: ethnography in a pop-up exhibition Architecture, multimodality and the ethnographic monograph

Taking a few moments here to talk about my ongoing - and evolving - research around assessment practice. Over time the interest of my PhD has broadened from the phenomenon of digital multimodal assessment to also ask questions more generally about the way that assessment practice in the Humanities is affected by the societal and pedagogical shift to the digital. In particular I am interested in investigating how:

In relation to the third of these lines of inquiry, I am particularly drawn towards sociomateriality's attention to the way that meaning emerges from a broader range of influences, opportunities, limitations and pressures beyond human interest and action. I think this is neatly captured by Fenwick, Sawchuk and Edwards when they propose that sociomaterial research looks to take account of:

In this way assessment feels less like a transaction between student and tutor, or a measure of academic performance, and much more like an assemblage of the seen and unseen, the human and machine, and beyond. As such, sociomateriality (supported by critical posthumanism) has had the effect of lifting my conceptual gaze from the ways that knowledge is conveyed and interpreted, to also take into account what previously seemed peripheral (or invisible or irrelevant) to assessment. This in turn has meant extending my ethnographic fieldwork where I have been observing students and tutors from undergraduate courses in Architecture and History. I have continued to investigate what takes place in the lecture theatre, studio, meeting room, corridor and canteen: at the same time though I have taken two further approaches in order to get a better sense of the resources and restrictions that influence the preparation of a piece of a coursework, whilst also investigating how digital literacy practices are enacted beyond what I was able to observe in class and around campus.

For the time being I am referring to this method as ‘digital sociomaterial journaling’, thereby acknowledging how my approach is influenced by Gourlay and Oliver’s recent proposal of longitudinal multimodal journaling (2016). Combining ethnographic approaches with an interest in sociomateriality and New Literacy Studies, Gourlay and Oliver describe research where they gathered journaling data in order to investigate the digital engagement of a group of postgraduate students. Amongst other methods, participants were provided with iPod Touch devices in order to gather data that would ‘document their day-to-day practices with texts and technologies in a range of settings’ (2016: 302), thereby offering insights into their digital literacy practices. As well as drawing inspiration from Gourlay and Oliver’s work, I have looked to some of my own earlier research where, along with my colleagues Sian Bayne and Michael Gallagher, we used the elicitation of 'digital multimodal postcards’ alongside semi-structured interviews to investigate how online distance students understand and enact their university, and how they construct space for learning (Bayne, Gallagher & Lamb 2013; Gallagher, Lamb & Bayne 2016). Here then is how these different methodologies have shaped my current research. Inviting students to record their surroundings as they work on an assignment For a period of approximately one week in the lead up to a recent essay deadline, five students from the American History course were asked to ‘record their surroundings' on every occasion they worked on the assignment. This included taking a photograph, making a one-minute ambient sound recording, and writing a short description of their location and activity at that moment in time. The data were then submitted electronically using a drop box on this website, via e-mail or USB drive. For the purpose of illustration, this is one of the six submissions that Sarah made as she worked on her assignment about the Civil Rights Movement.

Shadowing students as they work on an assignment

Two of the same students who recorded their surroundings also agreed to let me shadow them at different times as they worked on the essay assignment. In Karen’s case this comprised an afternoon in her flat followed by a later period in the main university library. For Harry meanwhile this involved a full day studying in one of the university's smaller libraries, as well as a nearby common room. As Karen and Harry worked on their essays (and drank tea, checked Facebook, listened to music and so on) I made my own sound recordings, took photographs and typed field notes. The following video gathers together representative sights and sounds from my first observation of Karen (although not as yet with the inclusion of entries from my field notes or reference to her Internet history for the corresponding period that she kindly agreed to supply me with).

The approaches described here were designed to shed light on the some on the recent interest of my research (bulleted above). For instance, how does the algorithmic code that is concealed, as Edwards & Michael (2011) suggest, beneath the sophisticated interface of software applications, influence the search results that appear in Google Scholar? How do perceptions and practices around plagiarism detection software influence composition (a concern recognised in research by Introna & Hayes (2011))? How does the use of sophisticated hardware and software pictured in the different images advance the notion of shared authorship between human and machine (see Knox & Bayne 2013)? Meanwhile, through the shadowing exercise in particular I have sought to gain insights into the ‘minute dynamics and connections’ that Fenwick et al. (2011, p.8) believe to be overlooked when we look to understand educational activities.

For the time being I am resisting the temptation to offer any sort of this response to these questions, not least as next month I will interview the same five students from the American History course. This will include discussion around the sights and sounds each student gathered as they worked on their essay assignment. Before that, for the purpose of comparison, tomorrow morning I will begin the same process all over again with five students from an Architectural Design course. A note on ethics Pseudoynms have been used in place of participant's real names. Students gave their consent to participate in the research described above, including the sharing of their supplied data. Participants were offered a £20 gift voucher for participating in each part of this research.

References

What follows is a short video that gathers together images and sounds I collected around a pop-up exhibition by second year Architecture students. As I have explained elsewhere on this blog, I currently spend every Friday in the Edinburgh School of Architecture and Landscape Architecture where I observe students and tutors as they participate in teaching, learning and assessment. This ties in with my Doctoral research into multimodal assessment across the disciplines.

Across five hours last Friday (14 October) I made dozens of sound recordings and took hundreds of photographs as students set up the gallery, arranged models for display and finally attended an exhibition of their own work, where they were joined by tutors and other members of the architecture school. The work on display comprised more than 2000 models constructed over the first five weeks of the Architectural Design course. Situating myself in the gallery for the afternoon I was able to observe the small archipelago of buildings sprawl into a city-in-miniature, with a broad panorama of approaches and imagination on display. The quality of work can be seen within the images in the video, but is also heard in the excited laughter during the exhibition of work: listen carefully and you might hear a student expressing how proud she is of what the group had achieved.

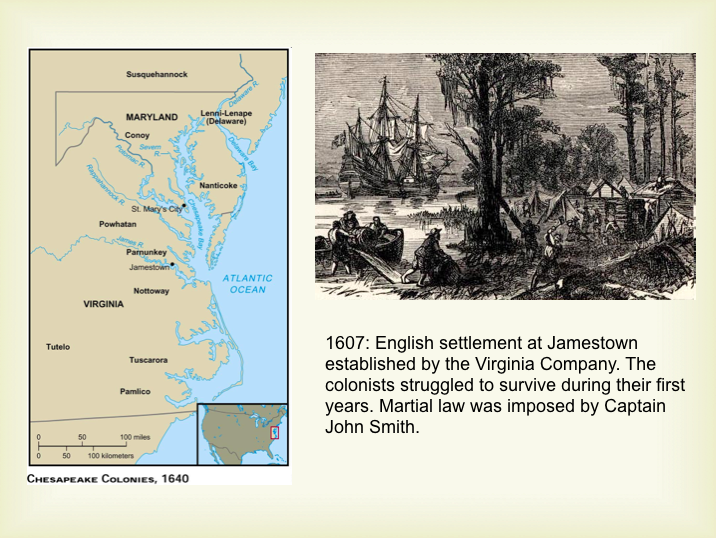

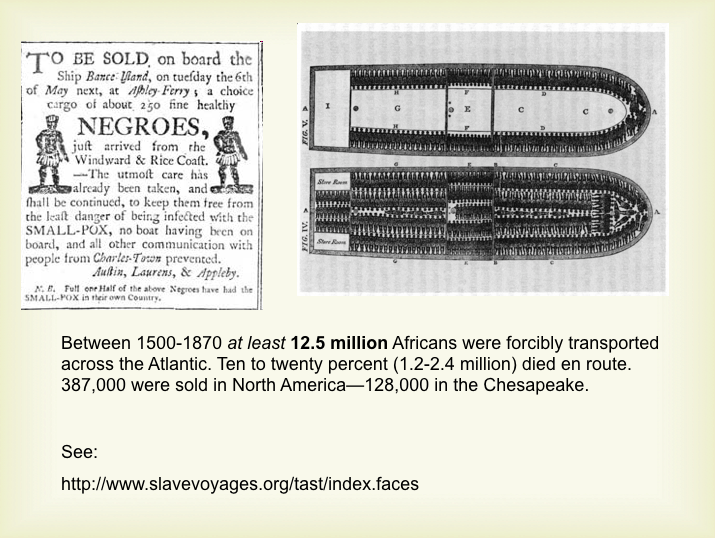

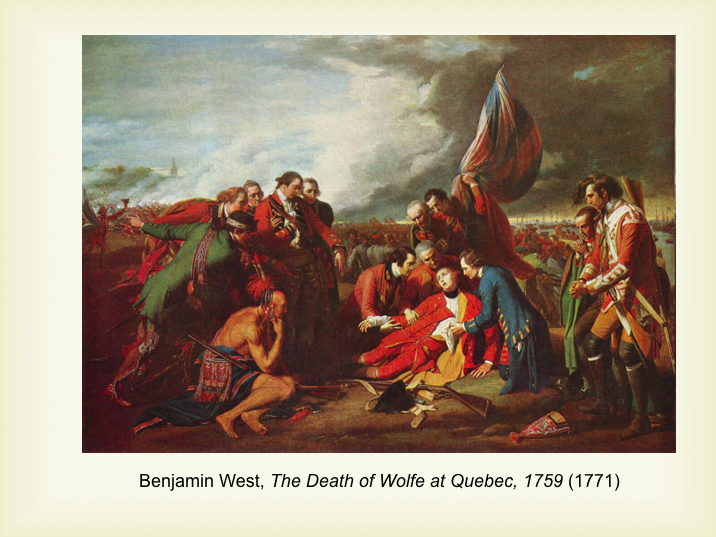

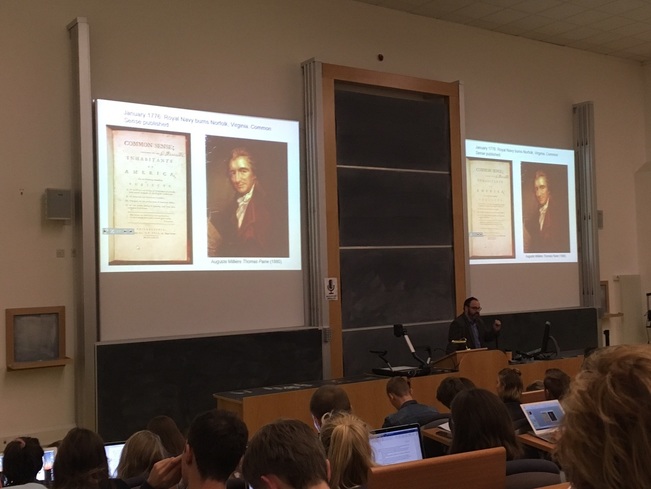

Through the gathering of aural and visual data I wanted to make a record of the pop-up exhibition that would inform my research: a piece of video ethnography to represent what would have been hard to achieve through written description or images-in-isolation. In the unrehearsed setting of the pop-up exhibition however I was thrust into the role of general exhibition helper. As I swept the floor and cut display paper down to size I gained a better appreciation of what was taking place than would have possible had I sat on the outskirts. If the ethnographer’s main instrument is him- or herself, in this instance it was accompanied by camera and audio recorder, brush and scissors. See also: Architecture, multimodality and the ethnographic monograph Looking beyond photos: the Architectural site visit Listening to the street As part of my Doctoral research into multimodal assessment in the Humanities I am undertaking an ethnographic study of an undergraduate American History course. I observe lectures, tutorials and other situations where students and tutors gather to construct meaning, as they explore The Making of the United States of America. There are two reasons I wanted to spend time in a History class. First, in common with the majority of Humanities courses, assessment within History programmes tends to privilege language, commonly in the form of the essay. Second, with its interest in visual artefacts as a means of study - drawings, paintings, maps, photographs - History has an eye for the way that images contribute towards understanding. Bringing these two ideas together, I wondered whether History programmes might be open to assessment practice where attention is paid to the visual, multimodal character of student work. Now that I have reached the third week of the History course (and have a couple of hours before the next class), I am recording some early observations about the role that images have played within classroom teaching. To begin with some context, this is a second year undergraduate course drawing students from a range of degree programmes. Three times a week the lecture theatre is packed with an audience of around 300, augmented by tutorials with groups of around 12 students each. In all of the classes the tutors have used PowerPoint presentations, with images to the fore. Something that really stands out from my field notes is that these images are always more than a backdrop: they appear central to the knowledge that the tutor wishes to convey. For instance:

In these instances the images work alongside the oral delivery, adding colour and context to what is being said. This isn’t to suggest say the lecturer’s oration and wider performance is presented in monochrome: on the contrary it is enthusiastic and eloquent. Simply, the images are vital in helping the tutor to convey meaning. Click on images to enlarge. Slides reproduced with kind permission of Professor Frank Cogliano. On other occasions the images are themselves the central focus of study. Cartoon depictions of individuals and events are used to prompt students to reflect on competing perspectives and attitudes of the time. Newspaper adverts and notices, variously drawing attention to slaves-absconding-or-for-sale, are themselves historical artefacts that demand discussion within the tutorial setting. For the most part the images on screen are accompanied by reasonably small bursts of text (typed words), mostly single sentence captions providing factual information: title, subject, author, date and so on. Three weeks into the course and I have yet to face down a single bullet point. In terms of both prominence and placement, text immediately seems to perform a functional supporting role to the central positioning and critical purpose of the image. This however disregards the presence of text within many of the images: a political proclamation or newspaper notice may be presented in j-peg format however the conveyed meaning is heavily dependent on the use of text. If we narrow our gaze from the slide in its entirety to instead see an image as a communicational act in its own right, we become aware of the intricate assemblage of meaning conveying resources sitting in juxtaposition: text, font, colour, spacing, layout and so on. When this is combined with the tutor’s oral delivery (volume, tone, pitch, pace, silence) and physical performance (eye contact with the audience, gesture, posture, movement across the space behind the lectern) we see that the History classroom is richly multimodal (or ‘densely modal’ to borrow from Norris (2004)) in the way that meaning is conveyed and interpreted. Picturing Thomas Payne in the richly multimodal History classroom In contrast to the highly visual and multimodal character of meaning-making in the classroom, assessment for the American History course privileges the use of written language. Coursework comprises two conventional essays while 20% of the final mark is based upon a ‘practical examination’ in the form of a student’s contribution towards tutorial discussion. To be clear, I am not suggesting that the assessment design is flawed in taking what Newfield (2011) and others might describe as a ‘monomodal’ approach: I am simply drawing attention to the way that it differs from what takes place in the lecture theatre and the tutorial room. When I come to interview course tutors at the end of semester I might find there is a very good reason why measurements of understanding and ability rely on language in its different forms. For the time being however, I have three questions to reflect upon in the coming weeks and months:

Before that however I have a lecture on The Origins of the American Revolution. I expect there to be bullets, but no bullet points. References:

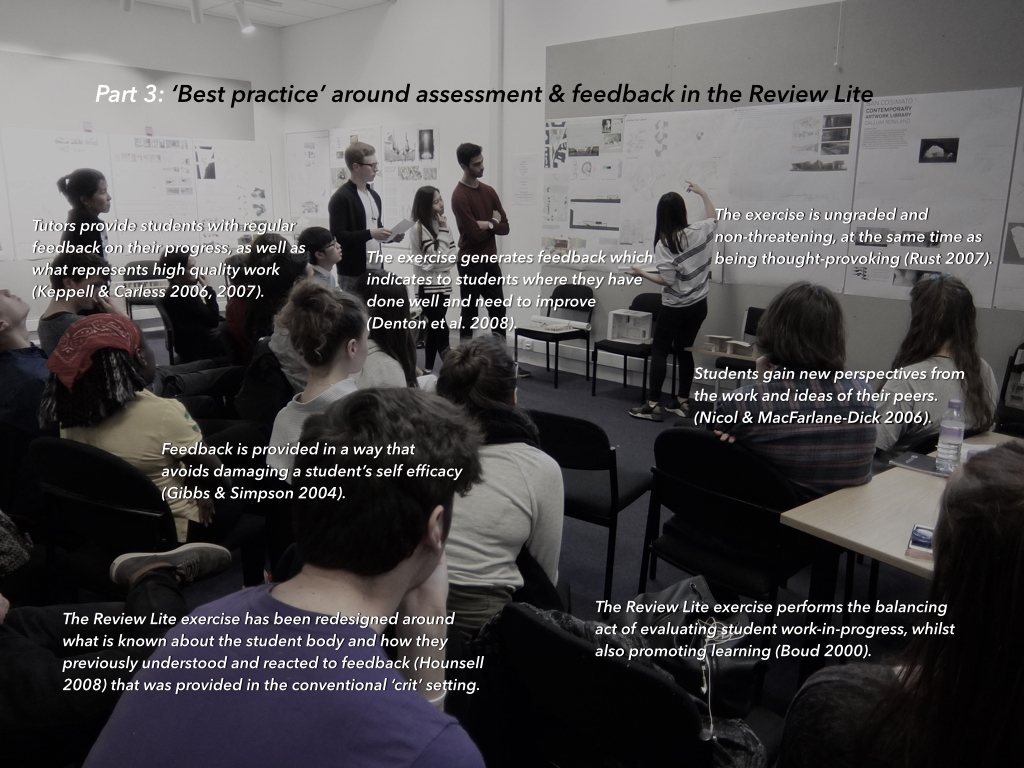

See also: Assessment, feedback and multimodality in Architecture Multimodality and the presentation assignment "I'm just glad it's not an essay!": a poster presentation assignment in music Drawing to a close my recent study of the meaning-making practices of Architecture students, I’m about to make a final visit to the Edinburgh School of Architecture and Landscape Architecture to share the findings of my ethnographic research. It also gives me a chance to observe tutors as they work as a team evaluating the quality of the completed library project portfolios that students have spent the term working on. My invitation this evening has come from Douglas Cruikshank who generously let me spend time observing students and tutors as they participated in a second year course in Architectural Design. I haven’t been quite sure how to pitch my presentation this evening, so I’m going to try and do three things. First of all I’m going to draw on my fieldwork report (my ethnographic study was partly a requirement of a course in Ethnographic Fieldwork that I commenced in January) where I argued that students and tutors enact power in the studio through the conscious use of space and silence. Second I’m going to use the visit as an opportunity to test out some ideas around multimodal meaning making in assessment, which directly aligns with the interest of my Doctoral research. Third, I’m going to try and give something more tangible back to the tutor team by discussing how the pedagogical approaches that I observed over the last three months sit in relation to what we might see as ‘best practice’ around assessment and feedback. Here are my slides: To begin, I should make clear that it was never the intention of my research to critique the practices of tutors, or wider course design or delivery within the Architecture programme. Nevertheless, in the spirit of the ethnographer returning to the field site to share findings that might be important or of interest to his or her participants, I think it’s important to spend a little of bit talking about what I’ve seen. At the same time, this is neither a hardship nor a situation that I need to approach with trepidation, not least as there’s a very positive story to tell. Whether through intentional course design, intuition or luck (although I doubt that), the teaching approaches I have observed during the Architectural Design course would seem to sketch a representative picture of many of the strategies we associate with ‘best practice’ around assessment and feedback. To illustrate this point, I’ve taken the example of the Review Lite, an approach used within the Architectural Design course to replace the intimidating and counter-productive ‘crit’ that has traditionally featured in visually-oriented creative programmes. Using an image I took during the Review Lite exercise I have attempted to show how ongoing tutor feedback, opportunities for experimentation, considering student attitudes, exposure to the work of peer, offering guidance on what represents high quality work - and other strategies - all come together to construct what would seem to on paper (and in my observed experience) to be a formative assessment experience that was highly conducive to learning. Mapping the assessment and feedback literature on 'best practice' against the Review Lite exercise

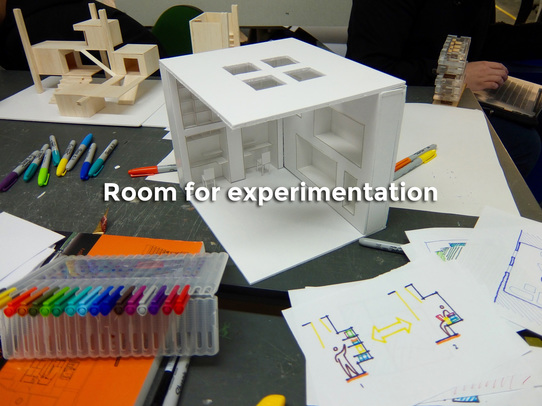

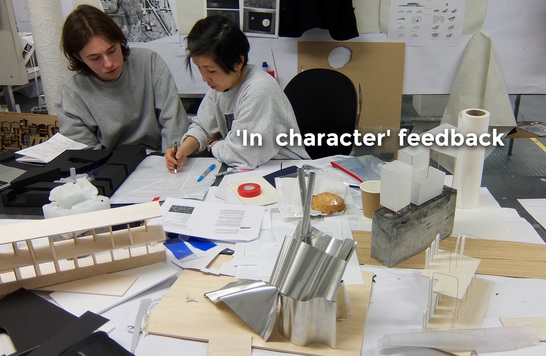

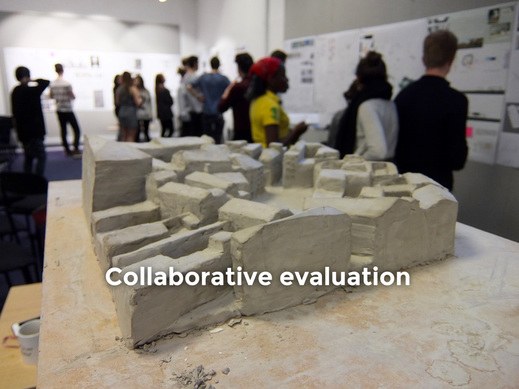

Between January and March this year I spent time in Edinburgh University’s Architecture School, observing a second year Architectural Design course. Over ten weeks I observed students and tutors involved in an assignment concerned with the design of a library. My interest was in learning how meaning was constructed and conveyed within a creative degree programme. In particular I wanted to gain insights into the ways that tutors and students approached an assessment exercise where work would be conveyed across a range of resources. Now that my ethnographic fieldwork has drawn to a close I have been invited to return to the Architecture School to share my findings. This has prompted me to spend some time thinking about what my experiences in the Architecture studio have to say about the relationship between multimodality and assessment and feedback within a creative setting. Looking back over my field notes and gathered photographs I have identified six themes which seem to stand out as being suggestive of the character of assessment and feedback in the Architecture Studio, as follows: A recurring feature of the Architectural Design course saw students being encouraged to explore relevant themes through drawings and models, which they would then bring to class each week. These artefacts would form the basis of tutorial discussion, where tutors and students would reflect upon the ideas being conveyed through the work. The environment was supportive and students were encouraged to use the preparation of these models and drawings as a way of experimenting conceptually with the design of their library building. At the same time, part of this experimentation pushed students to develop and refine their practical skills: my field notes describe how Maria had been investigating what happened to resin at high temperatures (it burned) and that Ellen had been exploring shape through the use of candle wax. Yet even at this formative stage there was encouragement from tutors towards nicely rendered sketches, polished architectural plans and accurate models: conceptual work and quality of finish. In this setting ‘risk free experimentation' did not mean ‘carefree’: students were encouraged to be ambitious and to bring new ideas and approaches to class, but that their creative energy should be directed towards the the acquisition of understanding and technique which would support their final coursework. This included thinking about the combination of resources that would be most suited to the ideas they wished to convey. This encouragement to be experimental was supported by feedback from tutors that was supportive and made use of dialogue that was in tune with the wider meaning-making rituals of Architecture. By 'In character' feedback I am suggesting that tutors engaged in a dialogue which displayed a symmetry with the approaches and artefacts that were the subject of discussion in class. For instance, when Jack (tutor) wanted to suggest an alternative way for visitors to circulate through Han's proposed library, he sketched directly onto his architectural drawings. Similarly, when Akiko (tutor) wanted Karen to think more deeply about the use of light in her proposed library, she took a pair of scissors and cut through her model to create a cross section that we could all peer into. In each case (and many other similar examples) this was accompanied by an oral commentary. Ideas were constructed and deconstructed using the same techniques for creating and conveying meaning - sketching, modelling, speaking - that students had used to develop their work and will be expected to use in Architectural practice. In the Architecture studio feedback is multimodal as well as in concert with the subject matter and the audience’s needs. From my fieldnotes, meaning was constructed and conveyed through: resin, acrylic, balsa wood, wire, wax, clay, plaster, card, wood, metal. Ink, paint, graphite. Ribbon, wool, netting. Light bulbs and scale plastic figurines. Hand-drawn sketches and computer-aided designwork. Photographs and architectural plans. Gesture, posture, eye contact. Voice. Space and silence. Printed type. Not all at the same time, yet always simultaneously drawing on a wide range of different resources (and more often than not, with words-on-page limited to playing a functional, descriptive role: ‘Scale 1:50’, ‘Elevation’). In the architecture studio meaning is constructed and conveyed in an array of richly multimodal ways, which in turn affects how tutors approach the task of marking assignments. Compared to 'essayistic’ assessment, the rich multimodality of the Architecture portfolio places a greater emphasis on acts of interpretation, rather than more straightforward measurements of quality. Although the marking of a conventional written essay requires the tutor to interpret what is being verbally conveyed, the existence of longstanding conventions around linearity, voice, argument and evidence lend a structure for evaluating the quality of ideas. The portfolio however draws on a combination of resources which speak with a less well articulated language (or indeed, range of languages). And whereas the essay has a pre-fixed format, the tutor evaluating a portfolio is challenged to interpret meaning from a collage of different materials, as the student composer has more freedom to bring her individual interests and talents to the fore. The tutor has to take account of how the different resources come together in concert or collision to create meaning. With a greater attention to freedom and interpretation, it is easy to see why tutors might not wish to work alone when it comes to evaluating and grading coursework... During the Review Lite exercise, students were divided into groups of three and then asked to circulate around the studio, reflecting on the designs being put forward by their peers. They jointly examined and discussed the ideas presented across the sketches and plans on display, before agreeing what they liked about the work and where they felt there was room for improvement. When it comes to assessing the final portfolios, tutors will work in pairs, moving around the studio and discussing how the presented artefacts sit in relation to the brief. In each of these examples the quality of ideas and work on display is evaluated through collaborative discussion between students or tutors. Through conversation and negotiation tutors arrive at an agreed position on how the collected models, sketchbooks and architectural drawings combine to address the assignment brief, followed by the grade that the work merits. When there is a high level of freedom in the representational form of the portfolio (for instance in the selection and use of materials and how they are configured in relation to each other) there would seem to be value in tutors working collaboratively to interpret and evaluate this highly multimodal work. As well as providing room for experimentation and opportunities for dialogue, the high level of student-tutor interaction during the Architectural Design course also seems to plays an important role when it comes to grading the student's overall work. Whereas in many subject areas, and particularly those which heavily privilege verbal communication, marking looks at the submitted work in a form of isolation or separation, a different approach exists in Architecture. In order to account for the learning that has taken place it is necessary to consider how students have approached the preparation of their work, the decisions they have taken and the paths they have followed. The normal university conventions surrounding anonymous marking are waived as tutors necessarily take account of the process as well as the final portfolio that is submitted for assessment. As one tutor described to me, the sketchbook can often be more revealing of the work undertaken and progress made by the student, than the curated final portfolio. If architectural drawings offer an incomplete picture of the learning that has taken place, the time spent together in class affords the opportunity to reflect on process as well as the final product. If we accept that meaning is socially constructed and shaped by cultural circumstances and personal histories, it would seem to make sense for tutors look to evaluate the quality of the work within, as opposed to isolated from, that situation in which it was produced. The six themes that I have described here represent an early attempt on my part to think about the relationship between multimodality and assessment & feedback within the Architecture Studio. Looking to the future I think it would be helpful to investigate whether the same approaches are a feature of other creative degree programmes. Before I do that however I will be sharing these findings when I return to the Architecture School next week. It will be interesting to see whether the Architectural Design tutors recognise the picture I have sketched of the meaning-making rituals that take place in their studio. With thanks to Douglas Cruikshank and the tutors and students within the Edinburgh School of Architecture and Landscape Architecture. Photographs were taken with the consent of the featured students and tutors. Pseudonyms have been used in the place of student names.

|

Search categories

All

I am a Lecturer in Digital Education (Education Futures), within the Centre for Research in Digital Education at The University of Edinburgh.

@james858499 [email protected] |

||||||||||||