|

This semester I am teaching on the An Introduction to Digital Environment for Learning course, part of the MSc in Digital Education at Edinburgh University. One of the objectives of our course is to provide students with an opportunity to experience a range of digital settings where teaching and learning take place. Going further, one of the blocks in our course is devoted to investigating the relationship between education, technology and space. Among other activities, students spend time exploring and building in Minecraft, while at the same time reflecting upon its potential to support learning.

To coincide with these activities, I spent time speaking with Tom Flint, Lecturer in Digital Media and Interaction Design at Edinburgh Napier University. The subject of our conversation was Tom's co-authored work around the creation in Minecraft of a facsimile of the Jupiter Artland scultpure park (Flint et al. 2018).

This shortened version of our conversation, juxtaposed with some of my own photographs and field recordings from Jupiter Artland and elsewhere, is one of the resources we are using in the An Introduction to Digital Environment for Learning course as we help students to think about the complex relationship between education, technology and space.

Perhaps the most interesting theme to emerge from my conversation with Tom was that we need to think of physical and networked environments as co-constituting, or what Nordquist & Laing (2015) and others have referred to as 'hybrid learning spaces'. When digital technologies have become so much a part of our everyday surroundings, perhaps there is a case for drawing on post-digital thinking (see Jandrić et al. for an introduction) to recognise the way that digital and physical environments are woven together into what we might call 'post-digital learning spaces'. Instead of thinking about either 'physical' or 'online' learning environments, perhaps we should instead recognise that many educational settings are shaped by spatial dimensions and the configuration of furniture, but also simultaneously by the flow of data and access to screen-mediated content.

0 Comments

This is a write-up of a recent event (23.02.18) I jointly co-ordinated with Michael Sean Gallagher, as part of the Festival of Creative Learning here at Edinburgh University. Michael has separately shared his own reflections of the event: I am linking to his piece although not reading it for the moment as I want to see how we experienced the activity from opposite sides of the table.

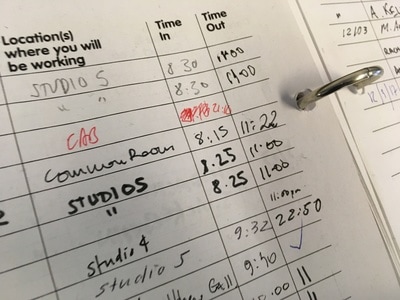

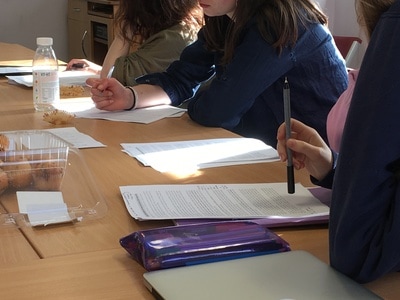

The ambitious title of our event was The Mobile Campus: Imagining The Future of Distributed and Digital Education at The University of Edinburgh. More succinctly, I saw two possibilities in the activity: first, that it might make the case for mobile learning as pedagogy; second, that we could raise questions about the way we conceptualise ‘campus’ and ‘university’ within increasingly digital learning environments. The ‘we’ in this case comprised Michael and myself, working with 24 participants. Without knowing the exact geographical spread of our group, we certainly had participants from across three continents, who joined us from a mixture of work, social, domestic and transitory spaces. For our part, Michael and I occupied a booth in the cafe of the University’s David Hume Tower. Our trans-continental class was made of learning technologists, academic staff, postgraduate students, doctoral and post-doctoral researchers and probably more besides. What everyone presumably had in common was an interest in exploring or shaping the future of digital education and pedagogy. Emphasising our interest in mobile learning, our promotional material explained that the event would be delivered through the Telegram messaging app and that participants could join us from wherever they were likely to find themselves at 1pm (UK time) on 23rd February. Telegram supports the easy (and relatively secure) sharing of images, sounds, words and other content: our event made good use of these features as participants responded through sound clips, photographs and typed messages to questions about the nature of the campus, community and pedagogy. As well as eliciting a multimodal conversation around the future of digital education, Michael and I used the format of the event to raise questions around traditional ways of thinking about the campus. The possibility that the campus is performed rather than being a collection of buildings is something that Michael and I have previously researched alongside our Digital Education colleague, Sian Bayne, as well as through a series of university workshops (references below). On this occasion, we were particularly interested in challenging the hierarchical ‘othering’ of the learning that takes place beyond the perimeter of the university’s real estate. Through our event we also saw an opportunity to blur the boundary between on-campus and online. We sought to achieve this firstly through the use of Telegram, where being physically present on a designated campus did not automatically presume some advantage over other locations or situations. Meanwhile, to dissolve the distinction between conventional and more social and domestic learning spaces, we visually projected our Telegram conversation, which was punctuated by images of participants’ learning spaces, into David Hume Tower. Here is is a sample of what participants shared: The visual traces of our wider campus were accompanied by a soundtrack, pulled together from participant audio recordings, combined with pieces of music nominated during discussion. Resulting from this, students and staff passing through the David Hume Tower cafe over lunchtime would have seen the Telegram dialogue thrown onto the wall of our booth, whilst experiencing a soundscape shaped by sounds from the wider learning space of the university: While this video clip is included to help explain how we made use of sound, it offers a further insight into our approach. In order that participants could see and hear what we were doing, Michael and I created a YouTube live stream, supported by Michael’s iPhone, an attachable fish-eye lens, a GorillaPod and a borrowed camera tripod. At the same time as merging the different learning spaces of our Telegram group with those in DHT, we were playing the scene back to the group. For a short time, at least, it felt like we were re-mixing the campus. Looking across some of the immediate feedback form our exercise I am really glad that our approach seemed to catch the imagination of some of the group:

What I am less sure about however is whether Michael and I struck the right balance between Telegram dialogue and attempting to engage with the group through the livestream. Although Michael and I had structured-in an ‘interlude’ where participants would shift their gaze from Telegram conversation to the live stream, before that happened we found ourselves attempting to simultaneously contribute to discussion through Telegram whilst responding orally through the live stream. I think perhaps the result was a bit messy (although certainly interesting). At the same time, I am not sure how well a Smartphone screen lends itself to flicking between the different spaces we were using.

All the same, when mobile pedagogy is sometimes seen as an outlier compared to more desk-based online education, I think it’s a testament to the possibilities of the form that participants were able to contribute whilst variously strolling for pizza at lunchtime, stuck in traffic or walking through the snow. This doesn’t mean that we should abandon the discussion board or other institutional collaborative spaces that are a staple of online learning, but I think our experience speaks volumes for the possibilities of mobile learning and how it can help us to re-think - and remix - the campus. References:

See also: Multimodality and mobile learning in Bremen The sonic spaces of online students Sound, including the practices of listening and production, have been used in a range of ways to ask questions around community, culture, power and other aspects of our social world. Researchers have turned a critical ear to the sonic environment in order to understand how sound can be used to construct personal space (Flügge 2011), exercise control and enact power in the hospital ward (Rice 2003) improve workplace efficiency (Bijsterveld 2012) and beyond. Elsewhere, reflecting the relationship between emergent technologies and the recording and reproduction of sound, Bull has studied rituals around the iPod (Bull 2005), Sterne makes the case for the MP3 as a cultural artefact (2006) and Prior has recently written about the complex hybrid of human-and-machine in the vocal assemblages of popular music (2017). These examples point to the growing recognition that sound has an important role to play in contemporary research, thus beginning to address what Bauer, writing almost two decades ago, saw as the absence of adequate methodology or mass of research to exploit the critical potential of sound within social inquiry (2000). These contemporary research-adventures-in-sound have started, in a small way, to challenge what Daza & Gershon describe as the ‘ocular hegemony’ of inquiry, through its devotion to the visual, to speech and to text (2015: 640). A survey of the literature concerned with sound in social settings describes research under the banners of acoustemology, acoustigraphy, acoustic ecology, anthropology of sound, ethnomusicology, pyschoacoustics, sonic cartography, sonic ethnography, sound studies and beyond. Considering the breadth of critical work that begins with sound, alongside the potential for these activities to ask questions around comprehension and epistemology, human relations and hierarchy, it is surprising to find that sonic phenomena and practices have rarely featured within education research. A rare voice in this respect is Walter Gershon who, in making the case for sound as educational systems (2011), questions the ‘scant study of sound in educational contexts either in or out of schools, other than as a distraction to learning.’ (2011: 67). In contrast, Gershon has used what he describes as ‘sonic cartography’ to explore ideas of race and place within the urban school classroom (2003) and more generally argues that an attention to the sociocultural character of sound provides us with insights into the construction of values in educational settings and the nature of meaning itself (2011). My own education research (investigating meaning-making around assessment) hears Gershon’s call for greater attention to sound as a means of inquiry around learning. Alongside the collection of field recordings in and around the classroom, I have collaborated with students in the creation of music playlists that accompany or inspire their work, and am gradually piecing together an interactive sound map that reflects how epistemology is enacted in the American History and Architectural Design courses that represent my field sites. More recently I have been thinking about whether I can produce sonic artefacts as a way of communicating some of the rituals and meaning-making practices that I have heard, seen and been told about within the dominant learning spaces of these two courses. Rather than simply writing about my experiences (with the associated problems of translating sounds into words) or re-playing recordings, I have been selecting and repackaging this sonic material, considered in the light of my wider research, in order to make arguments about the nature of meaning-making in different educational setting. There is a precedent for this approach - what we might call the critical manipulation of sonic research material - in Steven Feld’s influential work around acoustemology where he proposes a ‘a union of acoustics and epistemology’ that seeks to ‘investigate the primacy of sound as a modality of knowing and being in the world’ (2003: 226). Rejecting the tendency within ethnography to view sound as supplementary to the serious business of writing-up in monograph-form, Feld produces, manipulates and then releases sound recordings as a way of asking questions and conveying the ‘sense of intimacy and spontaneity and contact between recordist and recorded, between listener and sounds.’ (Feld & Brenneis 2004: 465). The case for this approach is further made within sound studies by Bruyninckx where he adapts Latour’s (1986) belief in the immutability and mobility of inscriptions (1986) to argue that a scientific approach to working with sound should allow the researcher to ‘dominate’ sonic material through cutting-up, recombining and superimposing what was collected (2012:143). As long as the sound recording can never accurately reproduce what was heard in the field (see amongst others Gallagher 2016 and Sterne 2006), we should take advantage of this detachment, Bruyninckx suggests, to meaningfully re-work the gathered sonic material. There are echoes in this work of speculative methodology which encourages imaginative approaches to social research in order to account for the complex and open-ended nature of our lived world. The remixing and repackaging of sonic material resonates with the creative capacity of speculative research (Ross 2016) as well as its interest in nuance and the unhinged rituals of everyday life (Michael 2017) over reproducibility and generalisability that dominates social research. Furthermore, the digital reworking of recorded sonic content, with the purpose of exploring and explicating ideas through research material and activity, is in tune with Ross & Collier’s (2016) call for methods that reflect the increasingly digitally-mediated nature of society. Combining the interests of speculative research and sonic artefacts as method, I have produced a sonic artefact for each of the American History and Architectural Design courses, primarily drawing on the dominant teaching and learning spaces of each course. Working through my field recordings and field notes, and influenced by ideas that emerged from observing, interviewing and photographing students and tutors across two semesters, each artefact talks about the nature of meaning-making in the corresponding course. The selection, configuration and prominence of the different phenomena (explained in the short commentaries below) are my attempt to use sound to explore and convey ideas around hierarchy, materiality, epistemology and pedagogy that reflect the broader interests of my research. What the artefacts do not attempt is a complete or accurate recording of what takes place in each learning space: the possibility of producing this type of record is challenged by the way that we each hear what we want to hear (Augoyard & Torgue 2005), that sound alters in response to the shifting presence of human and non-human bodies within any setting (Gallagher 2016) and the manner in which devices for recording and re-playing sounds deconstruct, filter and then repackage what is heard in the moment (Sterne 2006). Sonic adventures in American History This artefact is made up almost entirely of sounds recorded in (and around) the two lecture theatres and tutorial rooms where teaching was delivered across two semesters. The only exception is a short piece of conversation from a tutor’s ‘office hours’ that took place in a cafe adjoining the History department. Human voice - and more specifically that of the four lecturers and their tutor colleague - dominate this artefact, reflecting how classroom pedagogy depended heavily on a predominantly one-way communication of Historical knowledge. We briefly hear students discussing course content and an upcoming coursework essay (within a tutorial exercise; during office hours) however for the most part the presence of students is audibly present through typing, coughing, shuffling of paper, shuffling into class, and so on. At other times we can vaguely make out the sound of informal chatter as students wait outside the lecture theatre ahead of the scheduled start time: this period of anticipation or hiatus reflects the highly structured nature of the American History course. That we can hear the sound of students producing notes using word processor software (the clicking of keyboards) and also by hand (the zip of a pencil case opening, a fresh page being torn out of an A4 pad) reflects the different approaches I heard and observed during class. The audible contrast between keyboard composition and the more conventional technologies of rollerball pen and refill pad point us towards the varying literacy and meaning-making practices with a body of learners who are often lazily assigned the status of being entirely devoted to digital interests and rituals. Beyond the varying digital literacy practices of students, this sonic artefact makes three suggestions about the nature of meaning-making within the American History class: the communication of a body of Historical knowledge; the hierarchical authority of the lecturer, and; the heavy privileging of language (spoken, written, typed). Sonic adventures in Architectural Design The artefact for Architectural Design comprises field recordings from the design studio, exhibition gallery, lecture theatre, print room, crit room and site visit. For the most part however, we hear sounds from the design studio, reflecting its dominance as the space where students and tutors would congregate, and where students for the most part preferred to work. The artefact also captures the conversational nature of teaching and learning: a group tutorial; a one-to-one discussion between student and tutor; a group of students sharing ideas and offering each other feedback. The conversation does veer away from the subject of Architectural Design, however, as we hear students making chatting informally, laughing and generally enacting a sense of social amiability. Returning to the design-work-in-hand, there is the sound of constructing knowledge through technology (typing instructions into design software), paper (the rustling of posters) and other physical materials (sanding a block of wood), thereby reflecting the varied ways that meaning is constructed and conveyed within Architectural Design. We briefly hear music, on this occasion played through laptop speakers but more typically through earphones, when students wanted to enter an ‘auditory bubble’ (Bull 2005: 344) that would exclude the competing actions and distractions of those around them. The pedagogical approach in the Architectural Design course also placed importance on students explaining their work to an audience of peers and tutors, through a multimodal orchestration of voice, gesture, models and visual work: this can be heard in the sound of students presenting their plans-in-progress. If these artefacts immediately lack the coherence or order of more conventional approaches to communicating scholarship, they should heard in the context of John Law’s work around mess in social research. The fluctuating and occasionally jarring assemblage of sounds surely reflects the untidy reality of our world (and educational practices and spaces). The awkward orchestration of academic content, coughing and construction work penetrating the classroom alerts us to the minutiae that, according to Fenwick et al. (2011) have so often been overlooked in educational research, where inquiry privileges what Fox & Alldred (2017) describe as a ‘what works’ agenda, driven by a desire for outcomes and learning gains, over the complex reality of what takes place within learning events. What the different artefacts do not offer is a complete representation of the meaning-making that takes place across the two courses, only the work which happens in the major teaching spaces. It became clear in conversation and interview, as well as in the ‘digital postcards’ they sent me, that beyond the learning activities represented above, students would write and read, design and research, in a diverse range of settings. Assuming it was possible to gain regular access to these often private and occasionally impromptu study spaces, an alternative and more extensive sonic exercise might seek to account for learning that took place in the cafe, jazz bar, bedroom, train, plane, street and other settings that students described. Taking the example of the American History class, an attention to activities beyond the classroom would reveal how students use the body of knowledge communicated by tutors, demonstrated during other parts of my research, including the days I spent shadowing students in the lead-up to an essay deadline. A further limitation of this approach is that while I think the artefacts feature almost everything significant that took place in the different teaching and learning settings, the use of PowerPoint technology in American History lectures, and the consumption of food and drink in the Architectural Design studio, which were prominent in the visual research material I collected, do not register in my sound recordings and therefore do not feature in the pieces presented here. Therefore where the case is made for sonic methods in social research, this perhaps need to exist in conjunction with an attention to other sensory material in order to recognise that ‘regardless of how they are conceptualized, the senses are utilized in concert with one another’ (Gershon 2011:78). In justifying my own approach, the creation of the sonic artefacts presented here has been shaped by what I wrote, photographed, read and was told, as well as what I heard around the lecture theatre, tutorial room, design studio and beyond. From design studio to lecture theatre Finally, as my research is undertaking a comparative analysis of meaning-making across the two courses, I produced a third artefact that brings the two sonic pieces together. Assigning the sounds of the Architectural Design course to the left audio channel and American History the right channel, aural attention shifts over the course of one minute. The unexpected value of this third artefact is that it emphasises the shifting level of formality and student voice between the Architectural Design and American History courses in a way that was less apparent when listening to the individual sound pieces in isolation. More generally, listening to the different courses without interruption emphasises the contrast between the calmness, order and structure of the learning that took place in the lecture theatre, with the more erratic and creative energy of the design studio. In this way the configuration of each sound clip broadly exposes the nature of meaning-making in the two courses, something I am writing about elsewhere. At the same time this artefact reminds us that there are qualities and rituals that transcend disciplinary boundaries: the sound of students at work persists across the combined artefact, even if differently represented through sound. Further, in each case the learning that takes place is interspersed or accompanied by interests and activities beyond the immediate purpose of the Architectural or Historical project: air conditioning, passing cars and chairs; social media notifications, shuffling feet and the slamming shut of desks at the end of class.

References:

See also: Speculative Research feat. Slick Rick Processing sound for research The sonic spaces of online students

Edinburgh University’s Festival of Creative Learning sets out to explore innovative, imaginative and collaborative approaches to teaching. The focus of the Festival is a concerted and creative week of experimental learning activities between 19 and 23 February 2018, supported by pop-up events across the year. My contribution to the Festival, alongside my colleague Michael Gallagher, will comprise a series of provocations delivered via mobile messaging on what the future of distributed (and digital) education will be for the University.

We sketched out the idea for this event in September as we orchestrated a digitally-affected excursion through Bremen. Working in groups, conference delegates navigated their way through the city - and through a series of critical and physical prompts - mediated via their smartphones. Looking forward to the Festival of Creative Learning in February, we are re-thinking distance and location as we look to broaden our activity from a single city-centre to instead encompass participation across different continents. Alongside students and staff from Easter Bush, King’s Buildings and the Central Campus of the University, our event will aim to attract participants from much further afield. One of the arguments that Michael and I will make through our distributed activity is that within an increasingly networked world, mobile technologies can dissolve classroom walls and campus boundaries, as students and tutors in different locations are able to simultaneously and affectively participate in learning events. For the duration of an hour, students and staff in Edinburgh and elsewhere will simultaneously engage in conversation and activities, via their mobile devices, that encourage reflection on the future of education within increasingly digital environments. If my use of ‘Edinburgh and elsewhere’ would seem to de-privilege those students who engage with the university at a distance, this is simply because Michael and I have yet to spread the word about our event and therefore do not know where participants will be contributing from. One of most important features of our activity will be to challenge the distinction between ‘campus students’ and ‘distance students’ and the corresponding ‘othering’ of education that takes place beyond the bricks and mortar of the university campus, something that Michael and I explored with our colleague Sian Bayne in our work around the social topologies of distance students. To be clear, we are not arguing that a university’s real estate is insignificant either to students who regularly cross the campus threshold or those who view or imagine it from afar. With this in mind, as the event takes place Michael and I will be in the David Hume Tower cafe on campus, attempting to live mix and broadcast images and sounds generated from the exercise. If it goes to plan it could look and sound something like this:

Our event for Friday 23 February 2018 at 13.00 (Edinburgh time). If you are interested in participating or learning more about what we have in mind, please get in touch with Michael who will be glad to hear from you.

References: Bayne, S., Gallagher, M. and Lamb, J. (2013) Being ‘at’ University: the social topologies of distance students. Higher Education. DOI: 10.1007/s10734-013-9662-4 See also: Bremen: Multimodality and Mobile Learning The Sonic Spaces of Online Students Away from the University A short report on the walking activity that I delivered with Michael Gallagher last week, our contribution to the 3rd Bremen Conference on Multimodality. Through this 'paper-as-performance' Michael and I sought to make the case for the theoretical and methodological compatibility of multimodality and mobile learning, for instance as a way of investigating our urban surroundings. We also wanted to raise questions about the complex relationship between researcher and the digital, and how this might affect work within multimodality. You can read the background to our exercise on this project site, including a theoretical rationale which explains for instance why Smartphones and the Telegram app were central to the experience. We can't control the weather: surveying the skies above our meeting point ahead of the excursion. Despite rain directly beforehand, as well as a full day of conference activity, 19 colleagues assembled at Bremen's main train station to participate in the excursion. Michael and I were really glad that so many people wanted to take part in the walk, bearing in mind the inclement weather, fatigue and Bremen's competing evening attractions. Perhaps some of the enthusiasm we saw for the activity is reflected in the format of the exercise, explained in the invitation written into our conference abstract:

Rather than re-tracing what took place during the excursion I am instead making a record here of some of the key ideas that I will take away from the experience. This following points build on feedback we received after the excursion, as well as subsequent conversations between Michael and myself in the following days.

Perhaps more than anything though, what Michael and I were most excited about in the days following the excursion in Bremen was the potential for this type of digitally distributed mobile learning to be adapted to suit a range of different learning settings. When Michael and I first undertook one of these excursions in January 2015, alongside our colleague Jeremy Knox, we were foremost interested in the walking exercise as an approach that could be adopted in a range of different educational contexts. Looking back at our excursion through Bremen, I think we are getting close to where we wanted to reach. We wish to thank Andrew Kirk, Cinzia Pusceddu-Gangarosa (both University of Edinburgh) and Ania Rolinska (University of Glasgow) for pavement-testing earlier versions of the activity described here. Meanwhile Jana Pflaeging (Universitat Bremen) enthusiastically supported our plan to deliver this activity as part of the 3rd Bremen Conference on Multimodality.

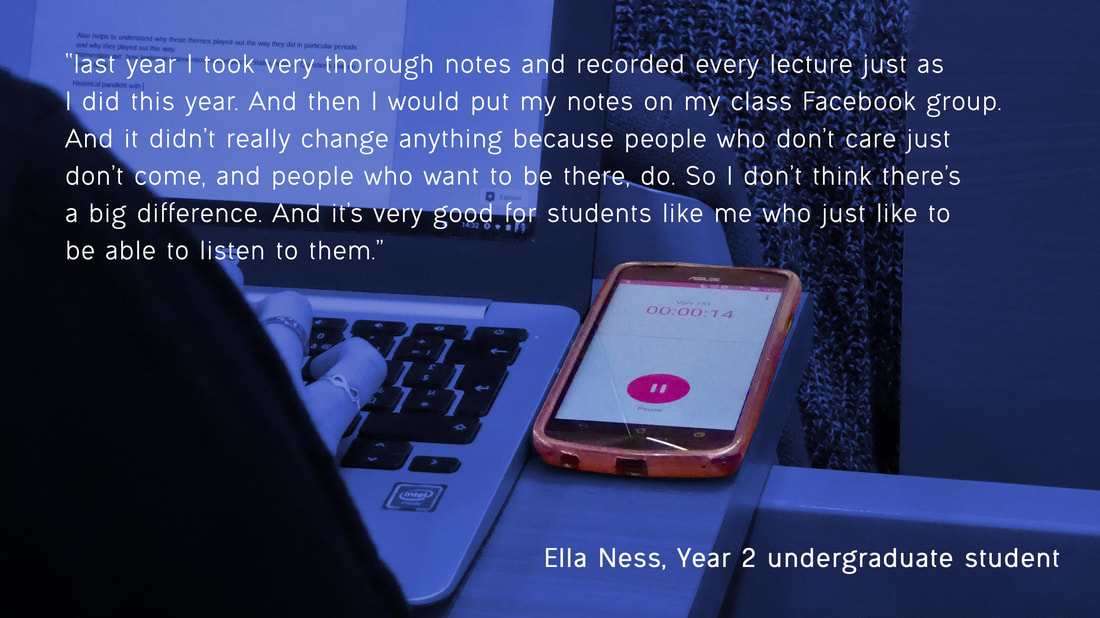

See also: Dialogue in the Dark Wondering about the city: making meaning in Edinburgh's Old Town Dérive in Amsterdam Over the past three months I have been interviewing students and tutors from an undergraduate History course as I have sought to understand how meaning-making around assessment is affected by the pedagogic and societal shift to the digital. One of the subjects that we discussed - often introduced as a topic of conversation by interview participants themselves - concerned the forthcoming roll-out of lecture recording technology here at Edinburgh University. With the consent of interview participants (comprising five students and five tutors, represented here using pseudonyms) I have reproduced and reflected upon some of the insights they shared. I make no claim to generalisability and what follows reflects the broader interest of my Doctoral research, pointing towards our complex relationship with digital resources. To begin, the interviewed students broadly saw lecture recording technology as a positive development, predominantly as a resource to return to after class. Suggested benefits included the possibility of revisiting complex ideas that had been covered during the lecture, or particular points where it hadn’t been possible to capture the detail put across by a lecturer. The availability of lectures on video was seen by one student as a "safety blanket" with others welcoming the way it would compensate for the occasions across the semester where illness prevented them from attending class. Several students pointed towards the value of lecture recording as a revision tool, enabling them to look back over lecture content some time after the classes had taken place. Meanwhile two of the students I spoke to also felt it would enhance the lecture experience itself as they would be able to spend more time thinking about what the lecturer was saying, rather than attempting to take notes. For their part tutors were overall less certain of the benefits that lecture recording would bring, whilst simultaneously recognising its inevitably. Questions were raised around whether it represented the best use of resources, how it might affect the natural rhythm of a course and most commonly, whether it would really support exam revision in some of the same ways that students had suggested:

Rather than positively contributing towards exam revision, some tutors instead suggested that any benefit was more likely to come from the (continued) support of students with learning adjustments, as well as those members of the class who had a first language other than English. Students who missed or misheard part of the tutor's oral delivery would have the benefit or re-watching the corresponding part of the lecture after class, it was suggested. While all five students that I spoke to broadly welcomed the roll-out of lecture-recording, this was accompanied by a sense of unease around some of its potential effects. A common thread across the interviews was that the convenience of watching video recordings of lectures would make the prospect of attending class less attractive. Lectures most at risk of dwindling attendance would be those taking place at the beginning of the day, those within courses that didn’t use exam assessment and, more bluntly, where the subject matter or its delivery was less than inspiring. For the most part these observations were made in relation to other students, rather than interviewees themselves. In fact, in contradiction to the current tendency to suggest that the conventional lecture has run its course, the students I spoke to were overwhelmingly positive about the lecture as a teaching method, pointing for instance to the enjoyment of watching highly skilled teachers, the structure that it lent to their pattern of study and, from a mental health perspective, as a way of getting them out of the house. Even if lecture attendance might lose out to the occasional lie-in, it remained a vital part of the university experience:

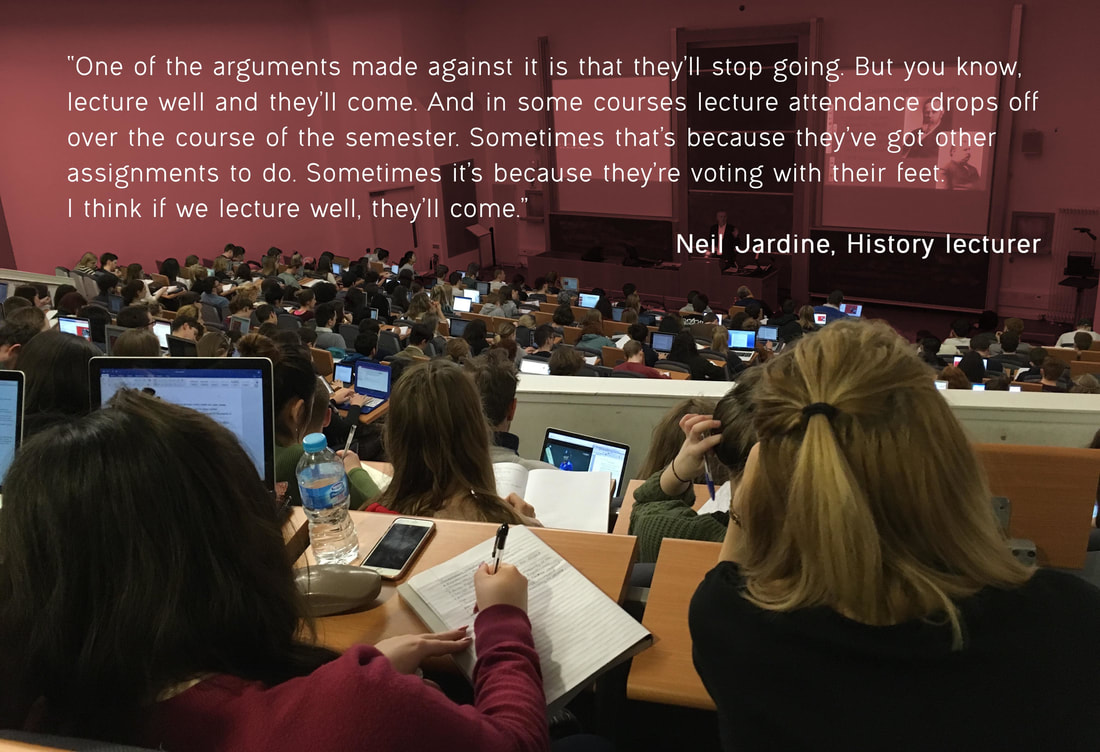

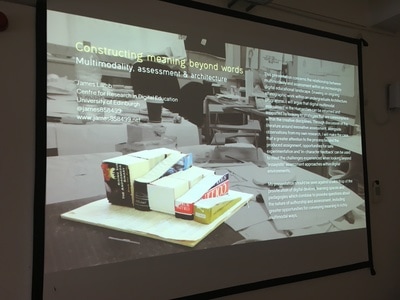

Adopting a position similar to that of their undergraduates, several of the tutors I interviewed felt that as long as the subject matter was interesting and delivered in an interesting way, most students would still prefer to attend lectures. At the same time there was an acknowledgement that attendance already tends to decline across the semester - and that some courses already give clear evidence of students "voting with their feet", as one tutor described it. What didn’t arise in conversation, but would be fascinating to observe next semester, is whether students with previously poor attendance might access more lecture content through the convenience of it being available online? Meanwhile, a further insight which would seem to reflect the neo-liberalisation of higher education, came from a student who suggested that as long as he was paying thousands of pounds in course fees he, rather than the university, had the right to decide whether it was preferable to attend lectures or to watch their recorded equivalent. Amongst the tutors more concerned about declining attendance there was a question over whether a video recording of a lecture represented a diluted version of what takes place in class. Reminding us that an effective lecture is more than the oral dissemination of content, one tutor pointed to the way that eye contact, conversation and physical movement towards the audience were aspects of the learning experience that would be lost on those viewing a video recording of the lecture. Furthermore, drawing on the experience of teaching on a MOOC, a tutor described the problem of teaching in the absence of the visual cues and other subtle forms of feedback that enhanced his delivery. Thinking about conceptual work around multimodality where it is argued that every communicational act depends on a range of different semiotic content (Jewitt 2009, Kress 2010), it is interesting to consider how the particular configuration of resources within the classroom lecture compares with a video-mediated equivalent (and how in turn this impacts upon knowledge-construction). For instance, how would the absence of eye contact and physical proximity to the lecturer affect interpretations of meaning around a video recording of a lecture?

Looking beyond the practice of delivery the lecture, all of the tutors I spoke to suggested that the content of their slides would need to adapt to recognise that they more explicitly had a life beyond the classroom. This wasn’t necessarily seen as a negative consequence of lecture recording: on the contrary a number of tutors admitted that in future they would pay closer attention to issues of copyright around the use of images. Potentially more problematic according to one tutor was the way that a video seen outside the setting of the lecture class might not convey nuance, potentially leading to misunderstandings and other consequences. The consensus across tutors however was that their approach to delivering lectures would not change in any great way. Several tutors pointed to the historical longevity of the lecture and its efficiency as a medium for reaching large numbers of students in a way that seemed to be positively received (a view supported by the students I spoke to). The overall sense I got from tutors was that, irrespective of the proposed benefits or possible problems attached to the roll-out of lecture recording, it wouldn’t dramatically affect their approach or indeed what takes place in the classroom.

If the classroom experience might largely remain the same, it is interesting to further consider how the experience of viewing a lecture recording might differ from being present in the classroom. It is instructive for instance to look at work by Dicks et al (2006) where they investigated the relative abilities of digital media to record events. While video is able to record moving image and sound, Dicks et al. helpfully remind us that it still offers a selective visual representation of the lecture, dependent upon the positioning and gaze of the camera. Without suggesting this would necessarily be a drawback, the experience of watching a video recording would exclude a panoramic sense of what is taking place in the lecture. Still with an interest in the character of digital recording technologies, it is also worth considering how the experience of viewing the video recording would be subject to the particular capabilities of the computer, tablet or smartphone that it is viewed upon. The visual culture scholar Nicholas Mirzoeff (2015) is amongst those who have drawn attention to the way that sophisticated sensors and code manipulate and reconstruct a digital representation of what is seen or heard. The question arises therefore as to how the exposition of meaning conveyed within a lecture is affected by the complex and concealed calculations that contribute to the way images and sounds are recorded and reproduced for later consumption in digital video form. Finally, without suggesting that the lecture setting is free from distraction (not least by the temptations of Facebook and internet shopping, as I have witnessed whilst observing the History course across two semesters), a number of the students I spoke to suggested that the classroom environment better enabled them to remain focused on the task in hand, compared to competing interests on or beyond the screen.

Thinking meanwhile about embodiment and sensory meaning-making (see for instance Pink 2009), the tactile, physical and corporeal experience of the lecture environment would inevitably be different from the cafe, student flat, library or wherever else a student might watch the video recording. If we accept that light, heat, temperature and touch contribute towards our disposition and therefore our learning, it is interesting to consider how meaning-making within an environment that is purpose-built for teaching might be different to watching a video recording in ostensibly social spaces.

As I wrote within the introduction to this post, my interest lies in the way that meaning-making is affected by the increasingly digital nature of higher education and society more generally. Lecture recording, as I have attempted to show here, is a single example of the complex relationship between student, tutor, subject and technology. In this instance I think it has also shown how vital and inspiring some of long-standing teaching traditions can be. While there was uncertainty expressed surrounding the impact of lecture recording technology, there will evidently continue to be a place for the skilled lecturer enthusiastically sharing his or her work with an interested and inquisitive audience. References

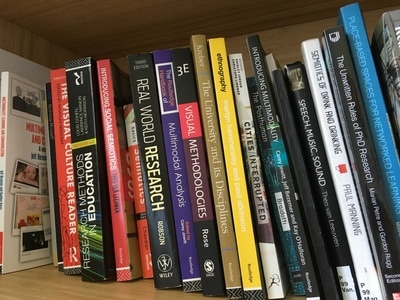

See also: How do students differently approach assessment? The visual, multimodal History classroom Next Tuesday (6 June), I will spend the day Exploring Visual Methods as a Developing Field, as part of an ESRC summer school taking place at Edinburgh University. Ahead of the event, which will be delivered by Professor Kate Wall from University of Strathclyde’s School of Education, participants have been asked to take 15 photographs which represent what we think it means to be a Doctoral student in 2017. From that we need to select a sub-set of 5 photos that best address the enquiry. Here is what I will be taking to the session: This photograph is intended to reflect how my research depends on both physical and online spaces and communities. My 'network' is made up of colleagues on campus who are also part of a larger dispersed group of researchers and lecturers, many of whom I have never ‘met’ beyond our exchanges in Twitter and in other digital settings. At the same time I am as likely to be talking about my research online, as on-campus. Something I really value about being a PhD student is having the flexibility to choose and move between different spaces that I think will support to the task I am working on at a particular time. The Psychology building on George Square is a good space to spend an hour of interrupted writing. Others locations on campus (and beyond) are better for reading, others for conversation, and so on. I usually begin each day with a plan of where I will work, depending on what I need to achieve. Edinburgh is full of pleasant and inspiring place to work. I'm lucky. This is my PhD supervisor, Sian Bayne, on a billboard outside Old College. There are a few of these posters dotted around campus and more than once they have reminded me that I owe Sian a piece of writing. Subliminal supervision. I have included this picture to represent how the expectations and direction set out by Sian and my second supervisor, Jen Ross, guide my research. If some of the other photographs here point towards the independence that comes with being a PhD student, it is accompanied by guidance and the encouragement to work to a high standard. This external hard drive represents the data I have collected over the last year whilst carrying out ethnographic field work. It contains thousands of photographs, hundreds of sound recordings and quite a lot of words. Most recently I've been adding lengthy interview recordings which had been exhausting my laptop. This image sheds light on the subject of my research, but also talks about the way that so much of my work is captured and condensed into ones and zeroes. My doctoral research takes place alongside other interests, activities and responsibilities. Before taking this picture I had been checking e-mail whilst my son had his breakfast. We were listening to music and talking about how long it would take to walk to the moon. After that it’s a rush to get out of the house before 7.45am. It felt important to include a photo which made the point that doing a PhD is never just doing a PhD. The possibility of attending evening seminars, travelling to conferences, taking advantage of study exchanges and other opportunities always depends on more than whether these activities match my research interests or if they justify the cost or time (and I'm not suggesting this is unique to me, of course). Here are the other images, meanwhile: Returning to the instructions for this exercise, we have been asked to print out the photos in order that they can be shared as part of a group exercise: it will be interesting to see how my own experiences of doctoral research sit along those of a wider group. Fascinating exercise, not least as I've been using image elicitation in my own research. Looking forward to it.

See also: Digital sociomaterial journaling Looking beyond photos: the architectural site visit The visual, multimodal History classroom Over the last year I have taken thousands of photographs whilst observing students and tutors from Edinburgh University's Architecture programme. At the beginning of this exercise I was mostly interested in recording what took place directly around assessment: preparing the portfolio, presenting work in a review exercise, practices around marking and moderation. Over time though I have sought to capture a broader range of phenomena as I have looked towards sociomateriality as the critical lens for my Doctoral research. From initially focusing on the meaning making rituals of students and tutors around assessment, I have instead been looking to the ways that knowledge construction in the Architecture studio is a more complex entanglement of human, technological and other material interests. Or as Fenwick and Landri describe in their work around sociomaterial assemblages in education:

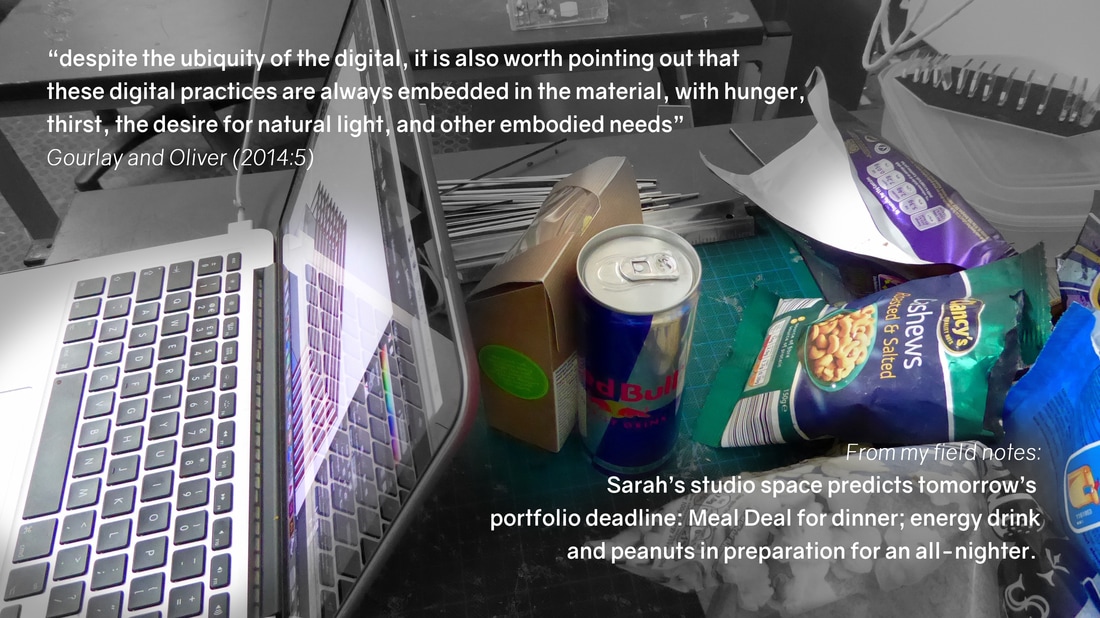

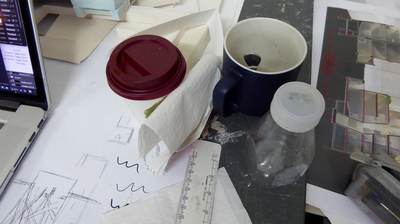

If I was initially guilty of viewing assessment in an overly simplistic way, as a fairly clear-cut exchange between student and tutor, sociomaterial critiques of education have instead encouraged me to examine the messy reality of what takes in and around the classroom, where 'learning is embedded in action and emerges through practice, processes that produce the objects and characteristics of educational events.’ (Knox and Bayne 2013). In this way assessment can be seen as a performance that depends on the student and tutor, but also looks to the role of curriculum, technology, sound, light, clothing and other visible and invisible actors within an evolving pattern of materiality (Fenwick et al 2011:8). What this has meant in practice is that, as well as continuing to photograph students and tutors in the Architecture studio, I have pointed my camera down at the floor and upwards to the ceiling. I have crawled under desks and balanced on chairs. I have photographed and recorded the sounds of ventilation shafts, data projectors, corridor conversation. I have attracted troubled glances from students unfamiliar with my research. Without having yet commenced my analysis of the gathered data, a recurring theme to emerge from my photographs and also my written field notes, is the way that food and drink seem to be an integral part of what takes place in the studio. Alongside the more recognisable tools of the architecture student we find snacks: pencils next to a packet of peanuts; chocolate alongside cardboard; Rhino with Red Bull. click on image to enlarge Through the image above I have tried to show how my field notes and photographs resonate with some of the principle ideas around sociomateriality within education, in this case echoing work by Gourlay and Oliver (2014) where they offer a sociomaterial account of digital literacy practices:

For the purpose of further illustration I have included below a small selection images which would seem to reiterate Gourlay and Oliver's call to remain alert to the way that our use of digital resources in education, for instance around assessment, is always and inevitably entangled with a much broader range of resources, influences, limitations and opportunities beyond the interests of the assignment task. click on images to enlarge References

See also: Digital sociomaterial journaling Camera, recorder, scissors, brush: ethnography in a pop-up exhibition Architecture, multimodality and the ethnographic monograph

Taking a few moments here to talk about my ongoing - and evolving - research around assessment practice. Over time the interest of my PhD has broadened from the phenomenon of digital multimodal assessment to also ask questions more generally about the way that assessment practice in the Humanities is affected by the societal and pedagogical shift to the digital. In particular I am interested in investigating how:

In relation to the third of these lines of inquiry, I am particularly drawn towards sociomateriality's attention to the way that meaning emerges from a broader range of influences, opportunities, limitations and pressures beyond human interest and action. I think this is neatly captured by Fenwick, Sawchuk and Edwards when they propose that sociomaterial research looks to take account of:

In this way assessment feels less like a transaction between student and tutor, or a measure of academic performance, and much more like an assemblage of the seen and unseen, the human and machine, and beyond. As such, sociomateriality (supported by critical posthumanism) has had the effect of lifting my conceptual gaze from the ways that knowledge is conveyed and interpreted, to also take into account what previously seemed peripheral (or invisible or irrelevant) to assessment. This in turn has meant extending my ethnographic fieldwork where I have been observing students and tutors from undergraduate courses in Architecture and History. I have continued to investigate what takes place in the lecture theatre, studio, meeting room, corridor and canteen: at the same time though I have taken two further approaches in order to get a better sense of the resources and restrictions that influence the preparation of a piece of a coursework, whilst also investigating how digital literacy practices are enacted beyond what I was able to observe in class and around campus.

For the time being I am referring to this method as ‘digital sociomaterial journaling’, thereby acknowledging how my approach is influenced by Gourlay and Oliver’s recent proposal of longitudinal multimodal journaling (2016). Combining ethnographic approaches with an interest in sociomateriality and New Literacy Studies, Gourlay and Oliver describe research where they gathered journaling data in order to investigate the digital engagement of a group of postgraduate students. Amongst other methods, participants were provided with iPod Touch devices in order to gather data that would ‘document their day-to-day practices with texts and technologies in a range of settings’ (2016: 302), thereby offering insights into their digital literacy practices. As well as drawing inspiration from Gourlay and Oliver’s work, I have looked to some of my own earlier research where, along with my colleagues Sian Bayne and Michael Gallagher, we used the elicitation of 'digital multimodal postcards’ alongside semi-structured interviews to investigate how online distance students understand and enact their university, and how they construct space for learning (Bayne, Gallagher & Lamb 2013; Gallagher, Lamb & Bayne 2016). Here then is how these different methodologies have shaped my current research. Inviting students to record their surroundings as they work on an assignment For a period of approximately one week in the lead up to a recent essay deadline, five students from the American History course were asked to ‘record their surroundings' on every occasion they worked on the assignment. This included taking a photograph, making a one-minute ambient sound recording, and writing a short description of their location and activity at that moment in time. The data were then submitted electronically using a drop box on this website, via e-mail or USB drive. For the purpose of illustration, this is one of the six submissions that Sarah made as she worked on her assignment about the Civil Rights Movement.

Shadowing students as they work on an assignment

Two of the same students who recorded their surroundings also agreed to let me shadow them at different times as they worked on the essay assignment. In Karen’s case this comprised an afternoon in her flat followed by a later period in the main university library. For Harry meanwhile this involved a full day studying in one of the university's smaller libraries, as well as a nearby common room. As Karen and Harry worked on their essays (and drank tea, checked Facebook, listened to music and so on) I made my own sound recordings, took photographs and typed field notes. The following video gathers together representative sights and sounds from my first observation of Karen (although not as yet with the inclusion of entries from my field notes or reference to her Internet history for the corresponding period that she kindly agreed to supply me with).

The approaches described here were designed to shed light on the some on the recent interest of my research (bulleted above). For instance, how does the algorithmic code that is concealed, as Edwards & Michael (2011) suggest, beneath the sophisticated interface of software applications, influence the search results that appear in Google Scholar? How do perceptions and practices around plagiarism detection software influence composition (a concern recognised in research by Introna & Hayes (2011))? How does the use of sophisticated hardware and software pictured in the different images advance the notion of shared authorship between human and machine (see Knox & Bayne 2013)? Meanwhile, through the shadowing exercise in particular I have sought to gain insights into the ‘minute dynamics and connections’ that Fenwick et al. (2011, p.8) believe to be overlooked when we look to understand educational activities.

For the time being I am resisting the temptation to offer any sort of this response to these questions, not least as next month I will interview the same five students from the American History course. This will include discussion around the sights and sounds each student gathered as they worked on their essay assignment. Before that, for the purpose of comparison, tomorrow morning I will begin the same process all over again with five students from an Architectural Design course. A note on ethics Pseudoynms have been used in place of participant's real names. Students gave their consent to participate in the research described above, including the sharing of their supplied data. Participants were offered a £20 gift voucher for participating in each part of this research.

References

The project New Geographies of Learning: distance education and being 'at' The University of Edinburgh set out to investigate how students participating in a fully online distance learning programme - the MSc in Digital Education - experienced and understood their university. Beginning in 2011, we spent a year gathering narrative and visual data, primarily through:

Our over-arching research question was: What does it mean to be a student at Edinburgh but not in Edinburgh, and what insight does this give us into learning design for high quality distance programmes? We addressed this question in two published journal articles:

More recently Sian Bayne, Michael Gallagher and I revisited the 21 digital multimodal postcards with an interest in exploring what they might tell us about the way that distance students construct and negotiate space for learning. Our approach and findings are described in a chapter 'The Sounded Spaces of Online Learners' within this recently published collection by Lucila Carvalho, Peter Goodyear, Maarten de Laat (2016):

To briefly touch on the way we approached the analysis of the postcards, we took a broadly multimodal approach which recognised that meaning emerged from the particular ways that the different semiotic resources came together in concert. This was augmented by looking towards Fluegge’s work around personal sound spaces (2011) from which we adopted and adapted the notions of territorialism, sonic trespass and spatial-acoustic self-determination. Within the visual realm meanwhile we looked to Rose’s 'site of audiencing' (2012). Our approach was also informed by Monaco’s ideas around coherence (2009) and similarly Van Leeuwen’s work in social semiotics around information linking (2004).

As we had hoped, by paying equal attention to the visual and aural (and the meaning that emerged from their juxtaposition), we gained fascinating insights into the ways that this particular group of students looked to construct and negotiate space. At times this challenged the conventional conceptualisation of distance learners, often depicted through a high level of mobility and digital sophistication. Instead we saw and heard the trappings of the domestic: family and soft furnishings; kitchen table and kettle boiling. We also became aware of how this group of students differently attempted to orchestrate or adapt to the material character of their surroundings. Without suggesting that our findings could be applied to online education across the board, we nevertheless believe that our methodology encourages teachers and course designers involved with online education to consider what is happening on the other side of the screen. Whenever I'm on campus I'm struck by the amount of attention that has gone into reconfiguring the different buildings into spaces that are conducive to learning. In comparison, there has been very little critical attention to the learning environments of online students. Through the findings and methodology described within our recently published chapter, we hope that we will encourage other researchers, teachers and programme designers to have a good look - and listen - to the learning spaces of online, distance students.

A digital postcard of Daisy's learning space in Xalapa, Mexico.

References:

See also: Away from the university Listening to the street Look! Listen! Learn! |

Search categories

All

I am a Lecturer in Digital Education (Education Futures), within the Centre for Research in Digital Education at The University of Edinburgh.

@james858499 [email protected] |