|

Recording the sound of the American History class, November 2016 Notes from a workshop delivered earlier today by Dr Martin Parker (Edinburgh College of Art) on the subject 'Processing Sound for Research'. This was part of the Digital Day of Ideas, organised by the Digital Scholarship team at Edinburgh University. Here is the abstract shared ahead of Martin’s session:

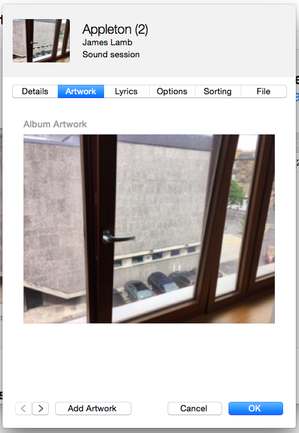

Outlined below are some of the ideas from the session that resonated most closely with my own research, including the gathering of ambient sound recordings as a way of investigating meaning making around assessment, as well as my work around the ways that online students negotiate and construct space for learning. To begin, there's a growing attention (in terms of the number of interested researchers and accompanying funding) in research that looks to sound in its various forms: sound is “an increasingly lively issue”, according to Martin. When undertaking these types of research however, we need to be aware that “sound is slippery”. It can be problematic in terms of how it is recorded, reproduced and more generally understood. At the same time “it’s now or never with sound”: compared to some other forms of data, sound appears and then vanishes in an instant, never to be heard again in the same way. The microphone is ambivalent to what we are interested in. As researchers we might be focused on what the interview participant is saying, however the microphone will likely be gathering many other (possibly competing) sounds - what Martin referred to as the "cocktail party" effect. This means its necessary to take extra care to where the recording device is placed and being pointed (for instance, the mic on an iPhone is counter-intuitively as the bottom of the device meaning it can often be unknowingly pointed towards the interviewee rather than the research participant). When we listen to a sound recording we are hearing the effects of the device. The particular qualities (and limitations) of the devices used for recording and reproducing sound will produce an aural representation of what was heard, not an exact record. We need to recognise and acknowledge this when we come to analyse or discuss the gathered data. When we play sounds, we need to recognise that an audience will hear more than we wanted them to hear. In Martin’s view this presents a need for particular methods and terminology designed around sound. Every room has what Martin described as a "sonic signature". At the same time, in some of the spaces where we teach and learn we’re being “assaulted by a whole range of sounds” over which we can exercise little control. The place where learning takes place can be a “really fraught space”. While there is a tendency in some places to fetishise the use of sophisticated technology around the recording of sound, this can act as a barrier to entry. In reality, all sorts of devices including SmartPhones and laptops are built with the capacity for recording sound. When we use devices such as the microphone on an iPhone to record sound we can actually gather a much richer set of data that extends beyond the research participant’s voice: we should acknowledge and exploit this. Sounds get lost and can be hard to find again (for instance in the way that are saved on devices). It’s essential then that we take care to save, tag and then file sound files as soon as possible after they are recorded. This can be helped by adding metadata to the audio file, even including a photograph of where the sound was recorded. Within iTunes for instance, it's possible add a whole lot of metadata to an audio file which, as well as documenting some of the detail around the sound recording, makes it possible to more easily search for data that otherwise might be hard to find at a later stage in the research process. Adding metadata to a sound recording.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Search categories

All

I am a Lecturer in Digital Education (Education Futures), within the Centre for Research in Digital Education at The University of Edinburgh.

@james858499 [email protected] |