|

I have been a little slow to share this article, published in Qualitative Research at the end of 2018, that I wrote with my colleagues Michael Gallagher and Jeremy Knox. It reports on a methodological exercise we took in London where we brought together ethnography, multimodality and urban walking. This involved making an unscripted walk through central London that we attempted to document through photographs and field recordings. This video goes some way to capturing what we did.

In the moments after drawing our excursion to a close, Michael, Jeremy and I began working through the data, generating some ideas that we presented at a conference the next morning (and we discuss in our article). This includes the potentialities of combining urban walking and ethnography, but also the limitations in our attempt to generate data as a way of reflecting on our relationship with the city.

Since undertaking that first exercise in London, Michael and I have subsequently adapted the approach as an alternative form of conference paper where we orchestrated a digitally-mediated excursion through the centre of Bremen. We have also more conventionally presented on this and similar methods, all of which combine digital technologies with urban exploration. See also: Exit the classroom! mobile learning and teaching Bremen: multimodality and mobile learning

0 Comments

Today sees the first Learning and Teaching Conference here at Edinburgh University, which takes as its theme, 'inspiring learning'. For my part, I will be presenting a poster, Exit the classroom! Mobile Learning & Teaching, alongside my colleague from the Centre for Research in Digital Education, Michael Gallagher. The poster follows a path across six different excursions or exercises where, along with our colleague Jeremy Knox, we have explored the possibilities of mobile learning and methodology. Beginning with a two-day workshop that Michael delivered in Helsinki in 2013, through events in London, Amsterdam, Edinburgh and Bremen, our poster makes the case for taking teaching and learning beyond the boundaries of classroom and campus. The final and most recent activity in this series was a fully online event delivered earlier this year within the University’s Festival of Creative Learning, where our group brought together students, teachers, researchers and learning technologists from across three continents and a range of academic disciplines. In each case our excursion (or that undertaken by participants) was digitally-mediated as we drew on the capabilities of smartphones, instant messaging services and other networked content or applications. Having previously spoken and written about these exercises (including an article for Qualitative Research that should be available any time now), on this occasion I wanted to share our work in visual form. If you happen to be at the Learning and Teaching Conference and are interested in the work described here, Michael and I be standing next to the poster between 12.50 and 13.40. We're conveniently close to the refreshments so grab a coffee and Danish and come and say hello. Or you can view and download a pdf copy of the poster here: A short report on the walking activity that I delivered with Michael Gallagher last week, our contribution to the 3rd Bremen Conference on Multimodality. Through this 'paper-as-performance' Michael and I sought to make the case for the theoretical and methodological compatibility of multimodality and mobile learning, for instance as a way of investigating our urban surroundings. We also wanted to raise questions about the complex relationship between researcher and the digital, and how this might affect work within multimodality. You can read the background to our exercise on this project site, including a theoretical rationale which explains for instance why Smartphones and the Telegram app were central to the experience. We can't control the weather: surveying the skies above our meeting point ahead of the excursion. Despite rain directly beforehand, as well as a full day of conference activity, 19 colleagues assembled at Bremen's main train station to participate in the excursion. Michael and I were really glad that so many people wanted to take part in the walk, bearing in mind the inclement weather, fatigue and Bremen's competing evening attractions. Perhaps some of the enthusiasm we saw for the activity is reflected in the format of the exercise, explained in the invitation written into our conference abstract:

Rather than re-tracing what took place during the excursion I am instead making a record here of some of the key ideas that I will take away from the experience. This following points build on feedback we received after the excursion, as well as subsequent conversations between Michael and myself in the following days.

Perhaps more than anything though, what Michael and I were most excited about in the days following the excursion in Bremen was the potential for this type of digitally distributed mobile learning to be adapted to suit a range of different learning settings. When Michael and I first undertook one of these excursions in January 2015, alongside our colleague Jeremy Knox, we were foremost interested in the walking exercise as an approach that could be adopted in a range of different educational contexts. Looking back at our excursion through Bremen, I think we are getting close to where we wanted to reach. We wish to thank Andrew Kirk, Cinzia Pusceddu-Gangarosa (both University of Edinburgh) and Ania Rolinska (University of Glasgow) for pavement-testing earlier versions of the activity described here. Meanwhile Jana Pflaeging (Universitat Bremen) enthusiastically supported our plan to deliver this activity as part of the 3rd Bremen Conference on Multimodality.

See also: Dialogue in the Dark Wondering about the city: making meaning in Edinburgh's Old Town Dérive in Amsterdam Briefly in Hamburg, travelling back from the 3rd Bremen Conference on Multimodality last week. I spent the day visiting museums in Hamburg's Speicherstadt, including the Dialog im Dunkeln attraction where, according to my tourist leaflet, there would be the chance to 'embark on a journey into total darkness' in order to 'learn the experience of everyday situations in life, without your sense of sight'. Although uncertain whether my absence of German language ability made this a good proposition, I paid the €21 entry fee: after all, it seemed to neatly fit some of the ideas we had recently been exploring in Bremen. I needn't have worried about my lack of language skills as the tour was expertly delivered in German and English by Bjorn, our guide. As Bjorn would explain during the journey, he has been blind since birth "because of a problem during incubation" and therefore has no sense of what it would be like to live with sight. He is a 29-year old music student, works part-time in Dialog im Dunkeln and has a wicked sense of humour.

After a brief introduction where we were provided with white canes and a very brief outline of what would follow, our party of eight (comprising two German families and myself) entered a world of complete darkness for the following 90 minutes (even if we had no sense of time, having been asked to place mobile phones and "any other shiny items" in lockers before hand). We moved through a curtain and made slow, awkward steps into a world of black. For the first while I wasn't sure whether to keep my eyes open and found myself instinctively looking around as I tried to get a sense of my surroundings. In the absence of sight we used Bjorn's voice - its assumed location and his clear instructions - to guide our path through a range of different environments. In each part of the tour the absence of sight drew attention to the way that we - and permanently blind members of our society - use other of the senses to understand their surroundings. Birdsong and the softness of the ground beneath our feet suggested our location within a park; gentle sideways rocking and the lapping sound of water accompanied our short tour around Hamburg's harbour, with Bjorn as the captain of our boat 'The Blindfish'; we used the sloping kerb and distinctive sonic-clicking of a pedestrian crossing to navigate a safe path through traffic. The only part of the journey that didn't work for me was when we stopped to listen to an 8-minute piece of music that was accompanied by an invitation to focus on the images that it conjured. This appealed much less than thinking about how I had already been creating vivid pictures during our journey as I drew on on my existing life experiences to picture what was in the different spaces. This in turn led me to consider how the journey through darkness resonated with some of the ideas that had been put forward within our discussions around multimodality in Bremen. During the multimodal walking excursion that Michael Gallagher and I had delivered in place of a conventional conference paper, participants were asked to spend a few minutes without speaking to their fellow group members. This short exercise adapted the 'clean ear' games of the acoustic ecologist R. Murray Schafer, that seek to emphasise the variety of heard phenomena we encounter, for instance by closing our eyes and attempting to foreground the aural. The activity presented by Michael and I differed in the respect that, by temporarily silencing spoken conversation, we wanted participants to recognise the broad range of meaning making phenomena that shape how we make sense of our surroundings (rather than focusing on the aural character of the street in particular). As a participant in Bjorn's exercise, I now recognised how my own meaning-making-without-sight was shaped by sound, movement, touch, smell and other sensory phenomena. A basic principle of multimodality is an openness to all the resources that have the potential to convey meaning. A second conceptual assumption is that all communicational and representational acts depend on more than one form of semiotic resource or 'mode'. Third, multimodality depends on the belief that the way we construct meaning is shaped by the way that these different resources come together in the moment. Continuing to ignore the ambient-folk soundtrack, I recognised how in each of the different settings - including those described above - I had made sense of my surroundings through a combination of sensory material. This was perhaps most evident when our journey visited a market and we sought to identify the wares on sale through touch combined with the distinctive aroma of particular fruit and vegetables: apples, oranges, cauliflower (I think). Although I didn't think about it at the time, looking back over the subject matter of the Bremen multimodality conference, there was a strong emphasis upon what is seen within multimodal resources and representation. This would seem to make natural sense in what is described as an increasingly visually-mediated world. At the same time though, Dialog im Dunkeln makes a strong case that we shouldn't neglect the other material that helps us to make make sense of our world, whether it can be seen or not. This being Germany, our tour concluded in a bar where (still in entire darkness) we drank coffee, coke or beer and reflected on our experiences. Before that though there was the practical and sensory challenge of attempting to judge the value of the coins in our pockets through weight, shape and size, before passing them to Bjorn, now in the guise of barman. As we stood at the bar Bjorn told us that he had recently returned from Birmingham where he had been delivering a training workshop for teachers working in a blind school. In reply I told Bjorn that each day I pass Edinburgh's own blind school, and that I was glad to now have a better appreciation of how the students there make sense of a world that we share, but they cannot see. In more ways than one, this journey into darkness had been enlightening. Danke, Bjorn. See also: Multimodality and mobile learning in Bremen Close encounters Processing sound for research

As part of the series of events organised by the Centre for Research in Digital Education at the University of Edinburgh, I recently (18 November 2016) organised a walking seminar through Edinburgh's Old Town. Along with my colleague Jeremy Knox, and joined by participants from inside and beyond the university, we undertook an unscripted excursion where our path through the city was shaped by our varying personal interests as well as the digital mobile devices we brought to the exercise.

Our activity can be situated within the growing critical interest in urban walking (Richardson 2015) as well as the tradition of walking ethnography (Vergunst and Ingold, 2008). Going back further, this type of unrehearsed excursion has its roots in the flânerie of Walter Benjamin and later the dérive of Guy Debord and The Situationst International. By moving our seminar beyond the physical boundaries of the university we dispensed with the abstract or agenda that often lend structure to on-campus conversation, instead inviting participants to bring their own research or professional interests to the exercise. We imagined that the excursion would be of interest to colleagues concerned with digital culture and mobile learning (see for instance Sharples et al. 2007) and those with an interest in how we construct meaning from our surroundings, for instance through sensory ethnography (Pink 2011), multimodality (Kress and Van Leeuwen 2001) or a sociomaterial sensibility (Fenwick, Edwards & Sawchuk 2011).

Across the duration of a lunchtime we walked and talked, sharing our interests, ideas and observations with our newly-found colleagues. At different locations that we broadly agreed to find interesting, we paused to capture our experiences on our mobile devices. This included the gathering of images and audio recordings, some of which are gathered together in the short video that offers a more rich and evocative record of what took place than I would have been able to offer through words.

Photos by Nick Hood, Hamish MacLeod and by me.

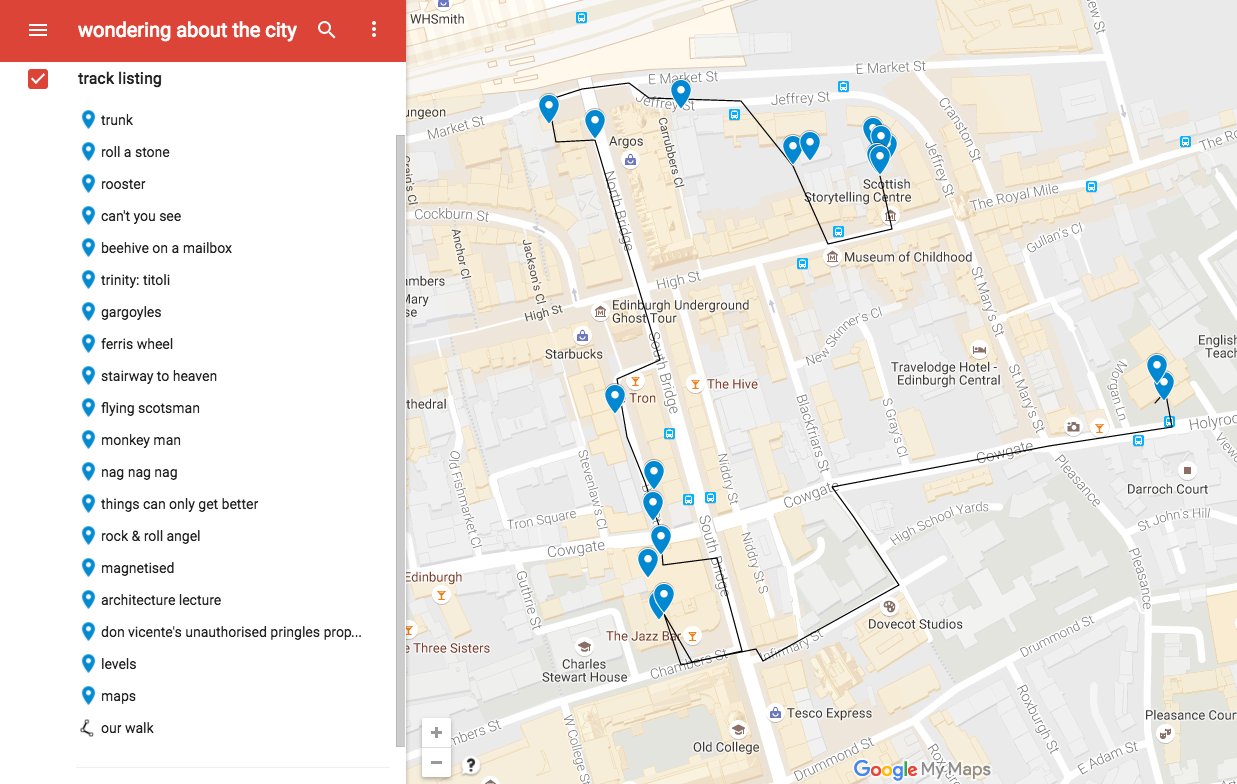

Another alternative and imaginative way that technology merged with our trajectory across the Old Town was provided by my colleague Jen Ross, where she compiled a live playlist on Spotify, triggered by her surroundings at different stages of our journey. Members of the group were drawn to Jen's approach and in turn suggested search terms for what became a collaborative playlist. Jen has since mapped the different songs onto the corresponding locations within an interactive Google map. The compiled playlist and map are worthy of space in their own right, however this screengrab presents an alternative way of representing our walk.

The different digital artefacts to have emerged from the excursion - video, music playlist, interactive map - go some way to reflecting the varying interests that participants brought to the exercise. At different times during our walk conversation turned to whether and how we felt this type of exercise might be used in different educational settings. Emergent ideas included:

In the days following our walk my colleague Christine Sinclair used ideas and images from the exercise as a way of encouraging students to reflect on the nature of space and place within the Introduction to Digital Environments for Learning course on the MSc in Digital Education. At the same time I am intrigued by the suggestion that this type of activity might help to break down the "clusters" that can form in university programmes where students from the same international communities group together, meaning that they miss out on what might be learned from their peers and their experiencing of the city beyond the vicinity of the campus. When Michael Sean Gallagher, Jeremy Knox and I first talked about the idea of enacting digital urban flânerie we were keen that, alongside a possible conceptual contribution, our methodology might be adopted and adapted into practical learning activities. Looking back on the excursion through the Old Town, I think there's mileage in this kind of activity. References:

See also: Multimodal dérive in Amsterdam Leaving do/Edinburgh Old and New EC1 (Sights & Sounds)

For the duration of this semester I am spending every Friday in the Edinburgh School of Architecture and Landscape Architecture, observing students and tutors involved in an undergraduate course in Architectural Design. This ethnographic study mirrors my fieldwork in an American History course where I'm observing tutorials and lectures, all in support of my Doctoral research into multimodal assessment across the disciplines.

Each visit to the Architecture School begins a little before 9am with a meeting of the course tutors. They discuss teaching, assessment and other aspects of the course. There is coffee, conversation and a passionate commitment to subject and students. After that the tutors make their their way to the design studio to meet with their groups. The studio occupied by these second year undergraduates achieves the effect of feeling subterranean without in fact being below ground: as one of tutors ruefully put it when attempting to sell the space to her group: "There's a window at the far end - make sure you all get a chance to look out of it." From the uneducated perspective of the observer, the creativity and imagination demonstrated in the models, sketches and other examples of student work sits in stark contrast to the seemingly drab and claustrophobic studio space in which they are constructed or displayed. It is something of a relief then that studio time is interrupted by excursions out of the Architecture building. So far this has included a visit to the Fruitmarket Gallery to see an exhibition by Damian Ortega ("To get you to really think about how you present your work in the studio" as a tutor introduced the exercise) and more recently by a site visit to King Stables Road in the heart of Edinburgh. The purpose of the visit to King Stables Road was to introduce students to the site for the architecture school they will design for their assessment exercise this semester. The group I followed were encouraged to spend time experiencing the environment that will be central to their thinking in the coming weeks and months. As we assembled in the shadow of Edinburgh Castle, the tutor encouraged the group to go beyond merely taking photos and to include time for discussing and reflecting upon what they experienced, in order that they would be able to make a visual, emotional response to the site ahead of the following week's tutorial. For the purpose of my own research I used my iPhone to gather some of the sights and sounds of the exercise, as the group navigated its way around the puddles, discarded wine bottles and polystrene takeaway detritus of King Stables road. I have collected the recorded images and sounds together within this short video:

While the video does the intended job of providing me with a record of the site visit, what it fails to do is adequately take account of the wider experience of the excursion, or the atmosphere in that particular corner of the city. This would seem to echo the tutor's instruction for students to talk and think about their surroundings, rather than rapidly traversing the site whilst gathering photos for later consumption. This emphasis on critical reflection-whilst-walking reminds me of the work of Dicks et al. (2006) where they introduced and critically considered the possibility of multimodal ethnography. Drawing on research where they investigated communication and meaning-making within a Science visitor centre, the authors reflected on the opportunities and limitations of gathering visual data, including photographs and video recordings. While these digital visual approaches were able to go beyond what it was possible to record using conventional field notes, they were insufficient in themselves to take account of movement and the materiality of a space. In response, the authors took to walking through the Science visitor centre in order to experience its ‘physical flow’ and ‘living, material, kinetic environment’ (2006:87).

As the architecture group made its way around the perimeter of the King Stables Road site all of the dozen students took photographs to a greater or lesser degree. In some cases this was augmented by making sketches, peering over walls and pausing to point out different aspects of the site. On another occasion around half of the group stopped for several minutes to variously take in the scene and enter into conversation. In this instance (which is seen and heard in the final photos in my short video), I would suggest that the students went beyond the gathering of photos to think about constructing meaning in-the-moment. Their gathering of photographic representations of the site was interspersed with discussion and then moments of silence as they seemed to reflect on what they could see, hear and feel around them. Perhaps the conclusion to draw here is that although photographs and video recordings provide a useful way of representing particular qualities of our surroundings, they cannot do justice to the sensation of being hit by water dripping from an overhead archway, or of the distinct aroma of last night's discarded take away and tonic wine. Reference: Dicks B, Soyinka B and Coffey A (2006) Multimodal ethnography. Qualitative Research 6(1): 77-96. See also: Multimodal dérive in Amsterdam Listening to The Street

Last Thursday and Friday (16 & 17 June) I attended the Visualizing the Street Conference, hosted in Amsterdam by the ASCA Cities Project. Alongside my colleague Jeremy Knox, I presented a methodology for investigating the city that drew on multimodality and mobilities (including Kress & Parcher (2007)), combined with the growing scholarly interest in urban walking (including Richardson (2016)). Our methodology involved undertaking an unrehearsed dérive through the city where we set out to gather aural and visual data that would provide opportunities for thinking about our relationship with the city. This methodology involved arriving early in Amsterdam ahead of the conference in order to undertake our walk around the city, before reflecting on the data and then pulling it together into something coherent ahead of our presentation the next day. Perhaps the most interesting part of our approach was that, for the most part, our route through the city was guided by the sights and sounds that grabbed our attention, reflected in the video below.

As we reflected on our experience in the hours following the dérive, one of the ideas to emerge was that while we might see ourselves as freely exploring the city, our path was also shaped by weather, building work, hunger and also self-preservation as we attempted to negotiate a safe route between bikes, trams, mopeds and canals. We became part of the city's network, subject to its flows and varying rhythms: with more time for reflection we would like to have explored how sociomateriality and posthumanism might differently theorise our approach.

Another idea to emerge in conversation was the importance of paying attention to the aural character of our environment. As the acoustician Trevor Cox has recognised (2014), for a long time we have heavily privileged what we see over what we hear, meaning that the aural character of our environment is under-theorised and under-considered. In our approach we attempted to turn up the volume on the city, as we simultaneously gathered sounds and images on our phones. When we later came to review this data it became clear that focusing on a single mode sometimes provided an incomplete or at times misleading representation of the city. At the same time, by looking beyond the visual we gained a more complete appreciation of our surroundings in the moment that we gathered our data, or as I put it during our conference presentation:

Here are the slides from our presentation, although unfortunately without the accompanying field recordings that we played to accompany our discussion.

References:

Following a path which deviates from the central interest of my Doctoral research, I’m spending a bit of time this afternoon drafting a paper for the Vizualising the Street conference in Amsterdam this June. The conference is being hosted by the Amsterdam School for Cultural Analysis (ASCA) Cities Project and will explore the impact of contemporary practices of image-making on the visual cultures of the street. Along with my colleagues Jeremy Knox and Michael Sean Gallagher I will be arguing that in order to better understand the city we need to pay greater attention to the aural character of our environment. This isn’t about disregarding the visual, but instead asking what happens when we consider sound alongside sight, and what implications this has for our ability to ask questions about our relationship with the city. That the aural character of urban space is under-considered is made loud and clear by Trevor Cox, Professor of Acoustic Engineering at the University of Salford. In Sonic Wonderland: A Scientific Odyssey of Sound, Cox proposes that:

The position Cox takes is built upon a career working as an acoustician, often attempting to understand and remedy the sonic deficiencies of spaces such as lecture theatres and grand concert halls. Amongst other things that we can take away from his work is that urban space both affects, and is affected by, sounds that reverberate between and within structures. I recently saw this point illustrated during a visit to Edinburgh University’s Architecture school where I observed students working on the design of a library building. Asked by the tutor to share their thoughts from a recent field trip to Rome, most of the group drew on notes to offer descriptive accounts of what they had seen. In contrast, one student, Alex, held his phone aloft and played two audio recordings he had made whilst walking the length of the prospective library sites. As he did this he provided a spoken commentary describing the changing nature of the soundscape as church bells came to the fore before being replaced by the bustle of a street market. This prompted us to consider how the library building might work in concert with the aural material of the city. Still in Italy, in his essay Recording the City: Berlin, London, Naples, sound artist and composer BJ Nilsen describes how sound recordings provide us with high levels of detail whilst helping us to travel back to the field site.

Returning to the Visualizing the Street conference, the paper I am writing just now requires that Michael, Jeremy and I arrive a day ahead of the conference in order to get lost in Amsterdam, just as Nilsen describes in his wander around the pescheria in Naples. The route we choose to navigate through Amsterdam will certainly be influenced by the sights that grab our interest, however we’ll also have an ear closely tuned to the sounds coming from the courtyards, canals and cafes that we encounter as we attempt to draw meaning from the streets of Amsterdam.

References: Cox, T. (2004) Sonic Wonderland: The Science of the Sonic Wonders of the World. London: Vintage Books. pp. 16-77 Nilson, B.J. (2014). Recording the City: Berlin, London, Naples. In The Acoustic City, Gandy, M. and Nilson, B.J. (Eds). Berlin: Jovis Verlas. pp. 57-58. See also: EC1: Sights and Sounds Architecture, multimodality and the ethnographic monograph The Sights & Sounds of Portsmouth & Southsea As background reading for a conference paper I'm working on, I've been reading about Psychogeography and other approaches to exploring and thinking about urban space. In his engaging (2010) study of the subject, Merlin Coverley presents Psychogeography as being interested in the places where Psychologogy meets Geography. Although 'nebulous and resistant to definition’, Coverley proposes that the different approaches to Psychogeography traverse some areas of common ground, most notably the pursuit of urban walking. This is often accompanied by what Robert MacFarlane (2005) describes as a calling to ‘Record the experience as you go, in whatever medium you favour: film, photograph, manuscript, tape'. How we approach ‘urban’ is also open to interpretation amongst Psychogeographers, shown each weekend in the routes followed along Fife coastal paths, and beyond the periphery of the London Orbital. Just as the city’s boundary is breached by lines of transport and communication, the parameters of what constitutes urban walking becomes blurred. And so a late-December walk through the growing darkness of the west Cumbrian countryside provided an opportunity to document the communications towers and power cables that we encountered on our winding path through the hinterland. The high tension lines pictured ibelow talk to us about the relationship between city and country, at the threshold between Psychology and Geography. It was only at the end of my walk that I became aware of plans to replace the pictured pylons with towers twice the size. At the same time I learned about a resistance campaign amongst residents along the planned route. High tension at the point where Psychology meets Geography. Coverly, M. (2010) Psychogeography. Pocket Essentials, Harpenden.

MacFarlane, R. (2005 ) 'A Road of One's Own'. Times Literary Supplement, October 7.

After fourteen enjoyable years working in widening access at Lothians Equal Access Programme for Schools, I'm about to follow a different path as I embark on a PhD in the School of Education at Edinburgh University. In place of a conventional 'leaving do' I convinced my colleagues instead to finish early on my last day and to take a leisurely stroll around the city, pausing for food, drink and conversation along the way.

The problem with this plan was that an amble around central Edinburgh during the Festival season would involve negotiating crowds of visitors and performers. Instead, I put together a route that would take in some of the city's quieter closes and streets, while at the same time visiting some of the locations that have featured in my working life over the last decade-and-a-half. Fittingly, we began in George Square where I was first interviewed for the job that I'm now leaving. Some hours later our journey drew to a close outside Moray House School of Education where I will take my first classes as a PhD student later this month. To add wider interest to our walk, I proposed that as we passed different sites of interest we should consider how they had changed over time. To help us do this, the night before our excursion I searched through the digital archives of the National Library of Scotland and SCRAN and bookmarked a series of buildings, streets and squares that we would likely pass on our route between George Square and Moray House. The different sites are foregrounded on my iPad in the images below. There's a juxtaposition here not just of new and old buildings, but of traditional and digital approaches to capturing images.

Something I like about the images is the trace of my work colleagues: their hands, cagouls and partial on-screen reflections. Bearing in mind how closely we have worked it was fitting that my colleagues should have a presence within the images. Another thing that strikes me about the images is the occasional lop-sided positioning of the iPad, reflecting the architectural imperfections and character that make up this part the city.

I also captured a short ambient audio recording at each site we visited. In a second representation of the collected data, the video below combines the sight and sounds of each of our stopping points.

I think the video-montage offers alternative insights into the same locations captured in the earlier slideshow. An obvious example would be how our journey was accompanied by the almost constant hum of traffic, even when there were few or no cars in view. Elsewhere, the sound of music, a child crying and a passing conversation about a visit to the zoo reveal a warmth, humour and emotion that isn't always present when we consider the photos in isolation.

The way that the introduction of sound contests the impression of contemporary Edinburgh presented in the slideshow prompts me in turn to consider whether the same rules might apply to the archived images. Or to put it another way, if we somehow had access to sound recordings taken at the time of the photographs of old Edinburgh, would we draw different conclusions about the stories that appear to be unfolding in some of the images? I wonder whether our understanding of how we used to live that we take from the apparent calm and tidy order of the archived images, would change if we were to hear the sounds pouring from the sepia-tinged breweries, printworks and classrooms that characterised Edinburgh's Southside a hundred years ago? See also: Urban flanerie as multimodal autoethnography and EC1: sights and sounds The sights and sounds of Portsmouth and Southsea Ultras EH9: Fan culture in south Edinburgh Maps, music and augmented reality The sights and sounds of matchday: FC St Pauli in Hamburg |

Search categories

All

I am a Lecturer in Digital Education (Education Futures), within the Centre for Research in Digital Education at The University of Edinburgh.

@james858499 [email protected] |