|

Earlier this year I completed my ESRC-funded PhD research which investigated the relationship between technology and the learning spaces of higher education. Prompted by a recent conversation among colleagues here at Edinburgh University about the potential of the digital dissertation, in this post I explain how my own thesis was presented in multimodal and digital form.

By ‘digital dissertation’, I am referring to the presentation of scholarship in overtly digital and multimodal form in those contexts where work is normally conveyed in a more essayistic and language-privileging format. At least in the arts, humanities and social sciences, it remains difficult to move beyond traditional print-based conventions within the high-stakes assessment setting. In the case of my own thesis, I sought to balance my desire to produce a richly multimodal and digital artefact, with University regulations and tacit disciplinary expectations around the exposition of knowledge. My wish to produce a digital dissertation came partly from my interest in multimodal assessment, as I have discussed in this journal article, this conference key note and other workshops with academic teachers. More important, though, was finding a representational format that would foreground the sonic and visual data around which much of my PhD was built. As I argue in the thesis itself, sound has tended to exist on the periphery of qualitative research (as discussed by Dicks et al. 2011) while the critical value of audio data has been undermined by a lack of consideration when reproducing sonic material alongside more conventional published researched (see in particular Feld & Brenneis 2004). The challenge I faced was to present audio and visual content in juxtaposition with written argumentation, while at the same time satisfying University regulations around the preparation of a traditional word-processed thesis. My response was to insert QR codes that linked to different types of digital artefacts. As I explained to the reader in the opening pages of my thesis, the intention here was that they could use a smartphone to access digital material alongside the printed content. True to one of the key ideas of multimodality, argumentation was made through the simultaneous juxtaposition of semiotic material, for instance words, images and sounds.

Therefore where my research involved the use of playlists as ethnographic artefacts, the reader was able to sample the nominated songs alongside my discussion of insights they had provoked into the way that learners used music to negotiate different types of learning spaces. These playlists – one for each of the American History and Architectural Design courses that provided the setting for my research - were hosted on the music-sharing platform Mixcloud. Here is the playlist I created with Architecture students:

Meanwhile in order to convey the sonic character of different teaching spaces, I created interactive sounds maps in Thinglink that situated ambient audio recordings and photographs against corresponding locations within diagrammatic floor plans. Here is the sound map for the area of the design studio where much of my field work took place:

Across more than a year of ethnographic field work I generated several hundred audio recording and thousands of photographs, some of which formed the basis of 15 short videos. Each video combined audio recordings, photographs and excerpts drawn either from my written field notes or from interviews. The following video captures the sights and sound of the architecture studio:

The creation of these different digital artefacts, combined with the way that they could be access via QR code, goes some way to showing how even within the constraints of producing a printed dissertation, it is possible to craft an artefact in digital, multimodal form. An important influence on my approach here was Kress’ work around aptness of mode (2005), the premise of which is that the digital form allows us to consider how we might shape the representational form of a digital artefact in a way that helps to best present the knowledge that is to be communicated. This meant producing a digital, multimodal thesis not for the purpose of experimentation, but rather because it was the most suitable way of executing arguments around the relationship between sound and physical space.

There are sure to be other and more imaginative examples of what a digital thesis can look and sound like, particularly when they emerge from the creative disciplines or within interdisciplinary contexts. And while my use of QR codes (rather than embedded content) may have been a neat concession to University regulations, it does feel like a compromise rather than a true use of the digital form. Nevertheless, I hope that my approach helps to stimulate more conversation about what is possible when it comes to producing richly digital and multimodal scholarship in an assessment setting, perhaps even contributing to conditions that are more conducive to this kind of work. References

1 Comment

I have been a little slow to share this article, published in Qualitative Research at the end of 2018, that I wrote with my colleagues Michael Gallagher and Jeremy Knox. It reports on a methodological exercise we took in London where we brought together ethnography, multimodality and urban walking. This involved making an unscripted walk through central London that we attempted to document through photographs and field recordings. This video goes some way to capturing what we did.

In the moments after drawing our excursion to a close, Michael, Jeremy and I began working through the data, generating some ideas that we presented at a conference the next morning (and we discuss in our article). This includes the potentialities of combining urban walking and ethnography, but also the limitations in our attempt to generate data as a way of reflecting on our relationship with the city.

Since undertaking that first exercise in London, Michael and I have subsequently adapted the approach as an alternative form of conference paper where we orchestrated a digitally-mediated excursion through the centre of Bremen. We have also more conventionally presented on this and similar methods, all of which combine digital technologies with urban exploration. See also: Exit the classroom! mobile learning and teaching Bremen: multimodality and mobile learning I’m in Odense today (8 Oct 2018) and am glad to be visiting the University of Southern Denmark as a guest of Nina Nørgaard and her colleagues in the Centre for Multimodal Communication. I have been talking about the relationship between multimodal assessment and feedback. These are my slides and references: Using multimodal artefacts created by students on the MSc in Digital Education, alongside my own experiences as a tutor, I argued that we should pay greater attention to the potential of multimodal feedback around assessment, for instance as a way of demonstrating the representational possibilities and academic validity of assignments crafted in multimodal form. Some of the ideas I talked about featured in my recent article in Multimodal Technologies and Interaction where I argued that multimodally-rich dialogue between teacher and learner can embolden students to be simultaneously adventurous, creative and scholarly in the assessment setting.

Considering the co-constituting nature of assessment and feedback it is surprising that there has been little critical interest in the relationship between multimodality and feedback, although work by Hung (2016) highlighted the potentialities of video feedback amongst students, while Campbell & Feldman (2017) are among those who have suggested that digital multimodal feedback might be an efficient way of engaging with large cohorts of learners. On previous occasions when I have had the opportunity to present my ideas to colleagues researching multimodality at University College London and University of Leeds I have come away with new ideas and ways of thinking about the subject. Today was no different. In the discussion that followed my presentation we talked about the way that multimodality often becomes confused with multimediality, and also what is potentially lost around what I'm going to call 'knowledge apprenticeship', when digital technologies are seen as a short cut to the acquisition of information and the production of multimodal artefacts. References

I am really glad to be delivering the opening key note presentation at today's Digital Assessment & Feedback: People, Places & Spaces conference at Lancaster University. I will be talking about Multimodality, Assessment and Feedback. These are the slides that I will be talking around: Although I have talked and written about multimodal assessment before, I am looking forward to arguing for greater attention towards the multimodal character of feedback and dialogue between student and tutor. When the teacher has an important role in encouraging students to recognise the scholarly validity of the digital multimodal form (Lea & Jones 2011), this can be achieved, I will argue, by presenting our comments, guidance or encouragement in corresponding form. Conversely, if our feedback is primarily conveyed through language (whether spoken or written) we implicitly defer to the power of words, while 'othering' alternative approaches as experimental or risky (and thereby less attractive in the high-stakes summative assessment setting).

Considering the intimate link between assessment and feedback, it is surprising that research investigating the relationship between multimodality and feedback is scarce (useful exceptions being work by Mathisen (2012) and Philips et al. (2016)). Plenty has been written about the possibilities and challenges of multimodal assessment however much less has been said about the way that, by taking a multimodal approach within their feedback, teachers can embolden and inspire students towards the representation of knowledge in ways that are simultaneously scholarly and in-tune with our increasingly digital and visually-mediated world. Thank you to Kathryn James and colleagues at Lancaster University for inviting me to speak at today's conference. References:

See also: Multimodality, assessment and language education Stories of transformative multimodal assessment Interweaving: multimodality, assessment and architecture Last Friday I visited the School of Languages, Cultures and Societies at the University of Leeds to participate in a seminar on the subject of Assessment and Feedback within Higher Education. I contributed a workshop around the possibilities and potential challenges of multimodal approaches to assessment and feedback within language education. Here are my slides with a full reference list at the end: Although I have been talking and writing about multimodal assessment for a few years now, the context for Friday’s event presented a new challenge. When the dominant discourse around multimodal assessment concerns a move beyond the central authority of words, does multimodal assessment have a place within courses with a central interest in the study of language (as opposed to using language to communicate meaning of other subject matter)? This question was the starting position for my session which included an activity where, working in groups, colleagues reflected on what might be the critical questions that language educators need to ask in order to ascertain whether multimodality might perform a role around assessment and feedback. Rather than responding to the suggestions from each of the groups, I instead recorded the different ideas (hopefully true their intention) and have grouped them under four themes, below :

Rethinking the nature of assessment

Assessment criteria and marking

Resource implications

Student needs and interests

Although many of the suggestions would apply to assessment and feedback practices across the disciplines, the centrality of language within the group's teaching meant that the workshop raised ideas that I hadn't encountered before. This provides a helpful reminder that the possibilities of multimodal assessment, and the potential barriers to its use, can vary across different learning contexts. Thank you to Chiara La Sala from the Leeds Centre for Excellence in Language Teaching for the invitation to contribute to Friday's event. Thanks Also to Martin Thomas and Elisabetti Adami who took time out to meet and explore ideas with me. See also: Stories of Transformative Multimodal Assessment Multimodality and Mobile Learning in Bremen Multimodal assessment in the presentation setting Earlier this afternoon I contributed to a Digital Transformation of Creative Industries conference here at Edinburgh University, which featured stellar presentations covering different aspects of digital culture and technology: sound, labour, heritage, journalism and beyond. Starting from the position that Architecture is one of the creative industries, I drew on my doctoral research to ask what we might learn from the richly multimodal, creative and inter-disciplinary approaches and conditions that exist around Architectural Design pedagogy. These are my slides: ...and this is an approximation of what I said:

Great to be a part of these conversations around the digital transformation of the creative industries.

A short report on the walking activity that I delivered with Michael Gallagher last week, our contribution to the 3rd Bremen Conference on Multimodality. Through this 'paper-as-performance' Michael and I sought to make the case for the theoretical and methodological compatibility of multimodality and mobile learning, for instance as a way of investigating our urban surroundings. We also wanted to raise questions about the complex relationship between researcher and the digital, and how this might affect work within multimodality. You can read the background to our exercise on this project site, including a theoretical rationale which explains for instance why Smartphones and the Telegram app were central to the experience. We can't control the weather: surveying the skies above our meeting point ahead of the excursion. Despite rain directly beforehand, as well as a full day of conference activity, 19 colleagues assembled at Bremen's main train station to participate in the excursion. Michael and I were really glad that so many people wanted to take part in the walk, bearing in mind the inclement weather, fatigue and Bremen's competing evening attractions. Perhaps some of the enthusiasm we saw for the activity is reflected in the format of the exercise, explained in the invitation written into our conference abstract:

Rather than re-tracing what took place during the excursion I am instead making a record here of some of the key ideas that I will take away from the experience. This following points build on feedback we received after the excursion, as well as subsequent conversations between Michael and myself in the following days.

Perhaps more than anything though, what Michael and I were most excited about in the days following the excursion in Bremen was the potential for this type of digitally distributed mobile learning to be adapted to suit a range of different learning settings. When Michael and I first undertook one of these excursions in January 2015, alongside our colleague Jeremy Knox, we were foremost interested in the walking exercise as an approach that could be adopted in a range of different educational contexts. Looking back at our excursion through Bremen, I think we are getting close to where we wanted to reach. We wish to thank Andrew Kirk, Cinzia Pusceddu-Gangarosa (both University of Edinburgh) and Ania Rolinska (University of Glasgow) for pavement-testing earlier versions of the activity described here. Meanwhile Jana Pflaeging (Universitat Bremen) enthusiastically supported our plan to deliver this activity as part of the 3rd Bremen Conference on Multimodality.

See also: Dialogue in the Dark Wondering about the city: making meaning in Edinburgh's Old Town Dérive in Amsterdam Briefly in Hamburg, travelling back from the 3rd Bremen Conference on Multimodality last week. I spent the day visiting museums in Hamburg's Speicherstadt, including the Dialog im Dunkeln attraction where, according to my tourist leaflet, there would be the chance to 'embark on a journey into total darkness' in order to 'learn the experience of everyday situations in life, without your sense of sight'. Although uncertain whether my absence of German language ability made this a good proposition, I paid the €21 entry fee: after all, it seemed to neatly fit some of the ideas we had recently been exploring in Bremen. I needn't have worried about my lack of language skills as the tour was expertly delivered in German and English by Bjorn, our guide. As Bjorn would explain during the journey, he has been blind since birth "because of a problem during incubation" and therefore has no sense of what it would be like to live with sight. He is a 29-year old music student, works part-time in Dialog im Dunkeln and has a wicked sense of humour.

After a brief introduction where we were provided with white canes and a very brief outline of what would follow, our party of eight (comprising two German families and myself) entered a world of complete darkness for the following 90 minutes (even if we had no sense of time, having been asked to place mobile phones and "any other shiny items" in lockers before hand). We moved through a curtain and made slow, awkward steps into a world of black. For the first while I wasn't sure whether to keep my eyes open and found myself instinctively looking around as I tried to get a sense of my surroundings. In the absence of sight we used Bjorn's voice - its assumed location and his clear instructions - to guide our path through a range of different environments. In each part of the tour the absence of sight drew attention to the way that we - and permanently blind members of our society - use other of the senses to understand their surroundings. Birdsong and the softness of the ground beneath our feet suggested our location within a park; gentle sideways rocking and the lapping sound of water accompanied our short tour around Hamburg's harbour, with Bjorn as the captain of our boat 'The Blindfish'; we used the sloping kerb and distinctive sonic-clicking of a pedestrian crossing to navigate a safe path through traffic. The only part of the journey that didn't work for me was when we stopped to listen to an 8-minute piece of music that was accompanied by an invitation to focus on the images that it conjured. This appealed much less than thinking about how I had already been creating vivid pictures during our journey as I drew on on my existing life experiences to picture what was in the different spaces. This in turn led me to consider how the journey through darkness resonated with some of the ideas that had been put forward within our discussions around multimodality in Bremen. During the multimodal walking excursion that Michael Gallagher and I had delivered in place of a conventional conference paper, participants were asked to spend a few minutes without speaking to their fellow group members. This short exercise adapted the 'clean ear' games of the acoustic ecologist R. Murray Schafer, that seek to emphasise the variety of heard phenomena we encounter, for instance by closing our eyes and attempting to foreground the aural. The activity presented by Michael and I differed in the respect that, by temporarily silencing spoken conversation, we wanted participants to recognise the broad range of meaning making phenomena that shape how we make sense of our surroundings (rather than focusing on the aural character of the street in particular). As a participant in Bjorn's exercise, I now recognised how my own meaning-making-without-sight was shaped by sound, movement, touch, smell and other sensory phenomena. A basic principle of multimodality is an openness to all the resources that have the potential to convey meaning. A second conceptual assumption is that all communicational and representational acts depend on more than one form of semiotic resource or 'mode'. Third, multimodality depends on the belief that the way we construct meaning is shaped by the way that these different resources come together in the moment. Continuing to ignore the ambient-folk soundtrack, I recognised how in each of the different settings - including those described above - I had made sense of my surroundings through a combination of sensory material. This was perhaps most evident when our journey visited a market and we sought to identify the wares on sale through touch combined with the distinctive aroma of particular fruit and vegetables: apples, oranges, cauliflower (I think). Although I didn't think about it at the time, looking back over the subject matter of the Bremen multimodality conference, there was a strong emphasis upon what is seen within multimodal resources and representation. This would seem to make natural sense in what is described as an increasingly visually-mediated world. At the same time though, Dialog im Dunkeln makes a strong case that we shouldn't neglect the other material that helps us to make make sense of our world, whether it can be seen or not. This being Germany, our tour concluded in a bar where (still in entire darkness) we drank coffee, coke or beer and reflected on our experiences. Before that though there was the practical and sensory challenge of attempting to judge the value of the coins in our pockets through weight, shape and size, before passing them to Bjorn, now in the guise of barman. As we stood at the bar Bjorn told us that he had recently returned from Birmingham where he had been delivering a training workshop for teachers working in a blind school. In reply I told Bjorn that each day I pass Edinburgh's own blind school, and that I was glad to now have a better appreciation of how the students there make sense of a world that we share, but they cannot see. In more ways than one, this journey into darkness had been enlightening. Danke, Bjorn. See also: Multimodality and mobile learning in Bremen Close encounters Processing sound for research Here are my slides from the Interweaving Conference at Edinburgh University earlier today (6 September 2017). I was presenting on the relationship between multimodality and assessment within increasingly digital learning environments and society more generally. The central argument of my research was that, contrary to the tendency within the literature to conceptualise multimodal assessment as being new, experimental or unconventional, this position might extend only as far as the boundaries of our own classrooms or disciplines.

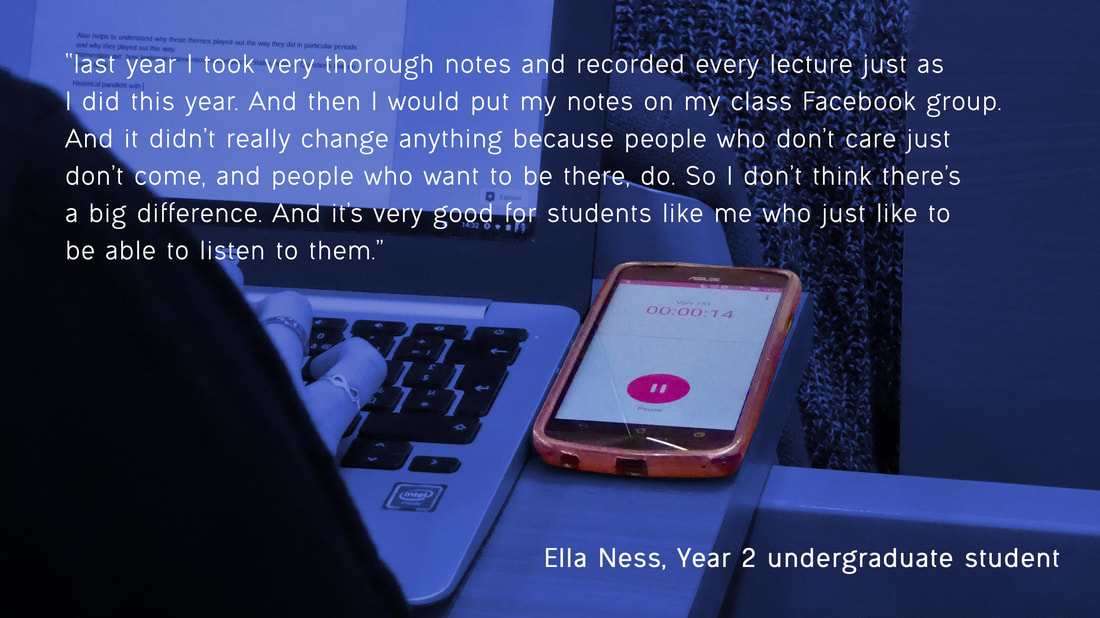

The literature that takes a specific interest in multimodality and summative assessment is dominated by those researching or working within what we might describe as ‘language-based’ courses and contexts: primary education literacy, secondary-level English, higher education Humanities; composition classes within US colleges and universities. Presumably this is because these are the subjects and disciplines that are most unsettled by the growing propensity towards richly multimodal ways of constructing and communicating meaning, prompted by the growing presence of digital devices, learning spaces and pedagogies in higher education. Drawing on my ethnographic study of meaning-making around assessment within an undergraduate architecture programme, I argued that multimodal assessment could be supported by what we might see as firmly established examples of ‘best practice’ around assessment feedback. If this seems a far from ground-breaking observation, it is worth noting that in the considerable body of literature that investigates the relationship between multimodality and assessment, including instances that have examined the introduction of richly multimodal assignments in place of the essayistic form, there are scant references to highly cited work around assessment and feedback. Similarly, there are few examples of researchers, course designers or tutors looking to the work of academic colleagues who are already immersed in multimodal teaching, learning and assessment. The Interweaving Conference set out to bring together the broad range of research and researchers working in education at Edinburgh University. In line with the interdisciplinary interest of the conference, I concluded my presentation by suggesting that in those situations where we look to introduce richly multimodal assessment to accompany or augment existing essayistic approaches, we might wish to travel beyond the boundaries of own disciplines - and the walls of our classrooms - to look at interesting and firmly-established strategies around assessment and feedback. See also: Visual and Multimodal Forum at the UCL Knowledge Lab Assessment, feedback and multimodality in Architectural Design Architecture, multimodality and the ethnographic monograph Over the past three months I have been interviewing students and tutors from an undergraduate History course as I have sought to understand how meaning-making around assessment is affected by the pedagogic and societal shift to the digital. One of the subjects that we discussed - often introduced as a topic of conversation by interview participants themselves - concerned the forthcoming roll-out of lecture recording technology here at Edinburgh University. With the consent of interview participants (comprising five students and five tutors, represented here using pseudonyms) I have reproduced and reflected upon some of the insights they shared. I make no claim to generalisability and what follows reflects the broader interest of my Doctoral research, pointing towards our complex relationship with digital resources. To begin, the interviewed students broadly saw lecture recording technology as a positive development, predominantly as a resource to return to after class. Suggested benefits included the possibility of revisiting complex ideas that had been covered during the lecture, or particular points where it hadn’t been possible to capture the detail put across by a lecturer. The availability of lectures on video was seen by one student as a "safety blanket" with others welcoming the way it would compensate for the occasions across the semester where illness prevented them from attending class. Several students pointed towards the value of lecture recording as a revision tool, enabling them to look back over lecture content some time after the classes had taken place. Meanwhile two of the students I spoke to also felt it would enhance the lecture experience itself as they would be able to spend more time thinking about what the lecturer was saying, rather than attempting to take notes. For their part tutors were overall less certain of the benefits that lecture recording would bring, whilst simultaneously recognising its inevitably. Questions were raised around whether it represented the best use of resources, how it might affect the natural rhythm of a course and most commonly, whether it would really support exam revision in some of the same ways that students had suggested:

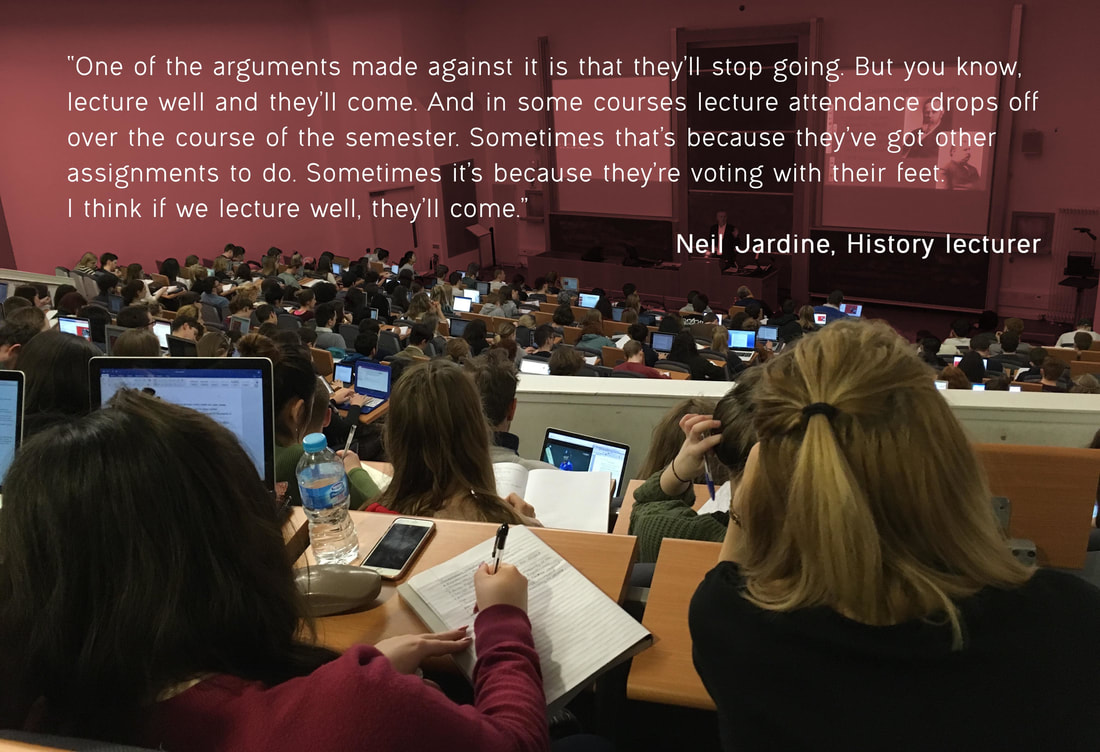

Rather than positively contributing towards exam revision, some tutors instead suggested that any benefit was more likely to come from the (continued) support of students with learning adjustments, as well as those members of the class who had a first language other than English. Students who missed or misheard part of the tutor's oral delivery would have the benefit or re-watching the corresponding part of the lecture after class, it was suggested. While all five students that I spoke to broadly welcomed the roll-out of lecture-recording, this was accompanied by a sense of unease around some of its potential effects. A common thread across the interviews was that the convenience of watching video recordings of lectures would make the prospect of attending class less attractive. Lectures most at risk of dwindling attendance would be those taking place at the beginning of the day, those within courses that didn’t use exam assessment and, more bluntly, where the subject matter or its delivery was less than inspiring. For the most part these observations were made in relation to other students, rather than interviewees themselves. In fact, in contradiction to the current tendency to suggest that the conventional lecture has run its course, the students I spoke to were overwhelmingly positive about the lecture as a teaching method, pointing for instance to the enjoyment of watching highly skilled teachers, the structure that it lent to their pattern of study and, from a mental health perspective, as a way of getting them out of the house. Even if lecture attendance might lose out to the occasional lie-in, it remained a vital part of the university experience:

Adopting a position similar to that of their undergraduates, several of the tutors I interviewed felt that as long as the subject matter was interesting and delivered in an interesting way, most students would still prefer to attend lectures. At the same time there was an acknowledgement that attendance already tends to decline across the semester - and that some courses already give clear evidence of students "voting with their feet", as one tutor described it. What didn’t arise in conversation, but would be fascinating to observe next semester, is whether students with previously poor attendance might access more lecture content through the convenience of it being available online? Meanwhile, a further insight which would seem to reflect the neo-liberalisation of higher education, came from a student who suggested that as long as he was paying thousands of pounds in course fees he, rather than the university, had the right to decide whether it was preferable to attend lectures or to watch their recorded equivalent. Amongst the tutors more concerned about declining attendance there was a question over whether a video recording of a lecture represented a diluted version of what takes place in class. Reminding us that an effective lecture is more than the oral dissemination of content, one tutor pointed to the way that eye contact, conversation and physical movement towards the audience were aspects of the learning experience that would be lost on those viewing a video recording of the lecture. Furthermore, drawing on the experience of teaching on a MOOC, a tutor described the problem of teaching in the absence of the visual cues and other subtle forms of feedback that enhanced his delivery. Thinking about conceptual work around multimodality where it is argued that every communicational act depends on a range of different semiotic content (Jewitt 2009, Kress 2010), it is interesting to consider how the particular configuration of resources within the classroom lecture compares with a video-mediated equivalent (and how in turn this impacts upon knowledge-construction). For instance, how would the absence of eye contact and physical proximity to the lecturer affect interpretations of meaning around a video recording of a lecture?

Looking beyond the practice of delivery the lecture, all of the tutors I spoke to suggested that the content of their slides would need to adapt to recognise that they more explicitly had a life beyond the classroom. This wasn’t necessarily seen as a negative consequence of lecture recording: on the contrary a number of tutors admitted that in future they would pay closer attention to issues of copyright around the use of images. Potentially more problematic according to one tutor was the way that a video seen outside the setting of the lecture class might not convey nuance, potentially leading to misunderstandings and other consequences. The consensus across tutors however was that their approach to delivering lectures would not change in any great way. Several tutors pointed to the historical longevity of the lecture and its efficiency as a medium for reaching large numbers of students in a way that seemed to be positively received (a view supported by the students I spoke to). The overall sense I got from tutors was that, irrespective of the proposed benefits or possible problems attached to the roll-out of lecture recording, it wouldn’t dramatically affect their approach or indeed what takes place in the classroom.

If the classroom experience might largely remain the same, it is interesting to further consider how the experience of viewing a lecture recording might differ from being present in the classroom. It is instructive for instance to look at work by Dicks et al (2006) where they investigated the relative abilities of digital media to record events. While video is able to record moving image and sound, Dicks et al. helpfully remind us that it still offers a selective visual representation of the lecture, dependent upon the positioning and gaze of the camera. Without suggesting this would necessarily be a drawback, the experience of watching a video recording would exclude a panoramic sense of what is taking place in the lecture. Still with an interest in the character of digital recording technologies, it is also worth considering how the experience of viewing the video recording would be subject to the particular capabilities of the computer, tablet or smartphone that it is viewed upon. The visual culture scholar Nicholas Mirzoeff (2015) is amongst those who have drawn attention to the way that sophisticated sensors and code manipulate and reconstruct a digital representation of what is seen or heard. The question arises therefore as to how the exposition of meaning conveyed within a lecture is affected by the complex and concealed calculations that contribute to the way images and sounds are recorded and reproduced for later consumption in digital video form. Finally, without suggesting that the lecture setting is free from distraction (not least by the temptations of Facebook and internet shopping, as I have witnessed whilst observing the History course across two semesters), a number of the students I spoke to suggested that the classroom environment better enabled them to remain focused on the task in hand, compared to competing interests on or beyond the screen.

Thinking meanwhile about embodiment and sensory meaning-making (see for instance Pink 2009), the tactile, physical and corporeal experience of the lecture environment would inevitably be different from the cafe, student flat, library or wherever else a student might watch the video recording. If we accept that light, heat, temperature and touch contribute towards our disposition and therefore our learning, it is interesting to consider how meaning-making within an environment that is purpose-built for teaching might be different to watching a video recording in ostensibly social spaces.

As I wrote within the introduction to this post, my interest lies in the way that meaning-making is affected by the increasingly digital nature of higher education and society more generally. Lecture recording, as I have attempted to show here, is a single example of the complex relationship between student, tutor, subject and technology. In this instance I think it has also shown how vital and inspiring some of long-standing teaching traditions can be. While there was uncertainty expressed surrounding the impact of lecture recording technology, there will evidently continue to be a place for the skilled lecturer enthusiastically sharing his or her work with an interested and inquisitive audience. References

See also: How do students differently approach assessment? The visual, multimodal History classroom |

Search categories

All

I am a Lecturer in Digital Education (Education Futures), within the Centre for Research in Digital Education at The University of Edinburgh.

@james858499 [email protected] |

||||||||||||||||||