|

The Assessment, Learning and Digital Education course, part of the MSc in Digital Education at Edinburgh University, sets out to explore how assessment is rapidly evolving in ways that exploit developments in digital technology and pedagogy. I'm glad to be a part of the course team, working with Clara O'Shea, Dai Hounsell and Tim Fawns. My major input to the course concerns multimodal assessment in digital contexts. Through the use of course readings, a discussion forum and an online seminar we explore ideas around digital literacies (see for example Lea & Jones 2011), the problematic nature of authorship (see for example Bayne 2006) and what happens when we newly introduce digital multimodal assessment into summative assessment (see for instance Adsanatham (2012) and De-Palma & Alexander (2015)). The recently re-designed assignment for this section of this course is a scenario-based activity where students are challenged to think critically about the conditions that support or exist in opposition to the introduction of richly digital multimodal assessment: I'm really looking forward to seeing what happens when students step into the tutor's shoes to advise colleagues on how to make digital multimodal approaches attractive and viable within the summative assessment setting! For the recent online seminar, I took the approach that where we look to introduce richly multimodal assessment into courses or programmes that have been particularly essay-centric or language-based, we might find it helpful to look to existing approaches from colleagues in other parts of the campus, particularly within what we might call the creative disciplines. Within the seminar I talked about my own research where, for the last year, I have been undertaking an ethnographic study of meaning-making practices around assessment in Architecture. This research is already described elsewhere on this blog therefore I'll make do here with sharing my seminar slides, which interweave some of my observations from the Architecture studio, with the literatures around assessment and feedback, multimodal assessment and digital literacies. References

0 Comments

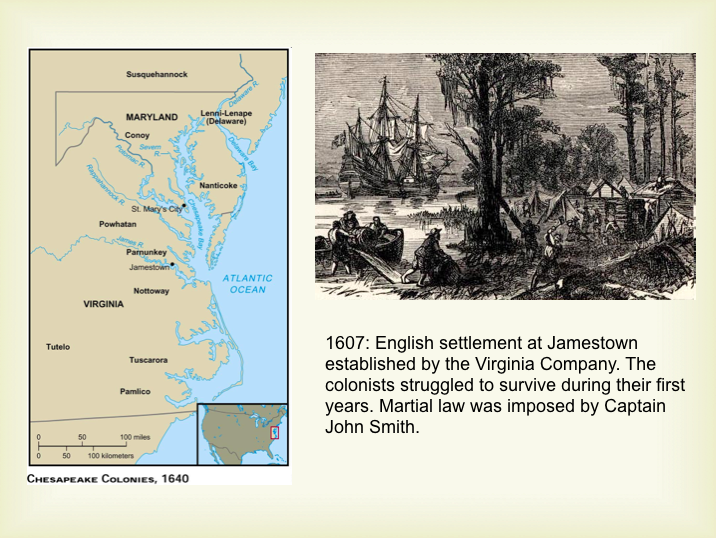

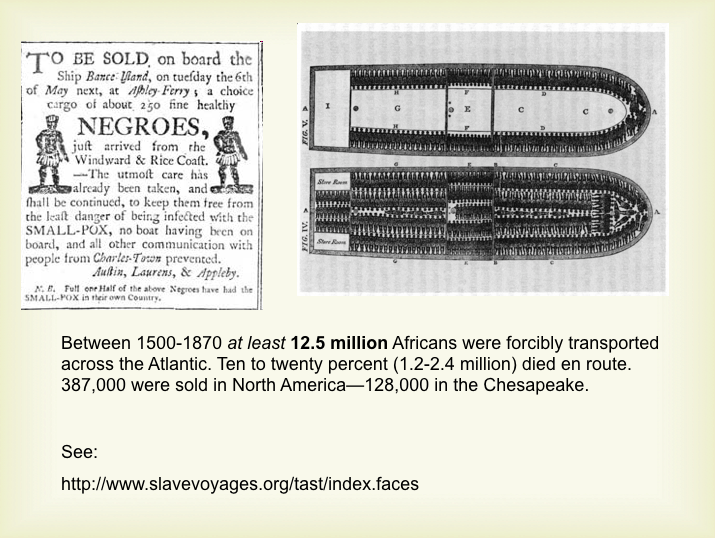

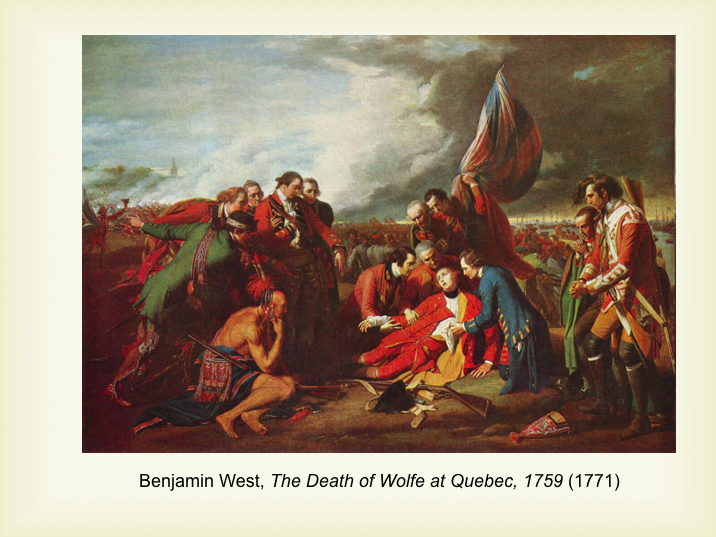

As part of my Doctoral research into multimodal assessment in the Humanities I am undertaking an ethnographic study of an undergraduate American History course. I observe lectures, tutorials and other situations where students and tutors gather to construct meaning, as they explore The Making of the United States of America. There are two reasons I wanted to spend time in a History class. First, in common with the majority of Humanities courses, assessment within History programmes tends to privilege language, commonly in the form of the essay. Second, with its interest in visual artefacts as a means of study - drawings, paintings, maps, photographs - History has an eye for the way that images contribute towards understanding. Bringing these two ideas together, I wondered whether History programmes might be open to assessment practice where attention is paid to the visual, multimodal character of student work. Now that I have reached the third week of the History course (and have a couple of hours before the next class), I am recording some early observations about the role that images have played within classroom teaching. To begin with some context, this is a second year undergraduate course drawing students from a range of degree programmes. Three times a week the lecture theatre is packed with an audience of around 300, augmented by tutorials with groups of around 12 students each. In all of the classes the tutors have used PowerPoint presentations, with images to the fore. Something that really stands out from my field notes is that these images are always more than a backdrop: they appear central to the knowledge that the tutor wishes to convey. For instance:

In these instances the images work alongside the oral delivery, adding colour and context to what is being said. This isn’t to suggest say the lecturer’s oration and wider performance is presented in monochrome: on the contrary it is enthusiastic and eloquent. Simply, the images are vital in helping the tutor to convey meaning. Click on images to enlarge. Slides reproduced with kind permission of Professor Frank Cogliano. On other occasions the images are themselves the central focus of study. Cartoon depictions of individuals and events are used to prompt students to reflect on competing perspectives and attitudes of the time. Newspaper adverts and notices, variously drawing attention to slaves-absconding-or-for-sale, are themselves historical artefacts that demand discussion within the tutorial setting. For the most part the images on screen are accompanied by reasonably small bursts of text (typed words), mostly single sentence captions providing factual information: title, subject, author, date and so on. Three weeks into the course and I have yet to face down a single bullet point. In terms of both prominence and placement, text immediately seems to perform a functional supporting role to the central positioning and critical purpose of the image. This however disregards the presence of text within many of the images: a political proclamation or newspaper notice may be presented in j-peg format however the conveyed meaning is heavily dependent on the use of text. If we narrow our gaze from the slide in its entirety to instead see an image as a communicational act in its own right, we become aware of the intricate assemblage of meaning conveying resources sitting in juxtaposition: text, font, colour, spacing, layout and so on. When this is combined with the tutor’s oral delivery (volume, tone, pitch, pace, silence) and physical performance (eye contact with the audience, gesture, posture, movement across the space behind the lectern) we see that the History classroom is richly multimodal (or ‘densely modal’ to borrow from Norris (2004)) in the way that meaning is conveyed and interpreted. Picturing Thomas Payne in the richly multimodal History classroom In contrast to the highly visual and multimodal character of meaning-making in the classroom, assessment for the American History course privileges the use of written language. Coursework comprises two conventional essays while 20% of the final mark is based upon a ‘practical examination’ in the form of a student’s contribution towards tutorial discussion. To be clear, I am not suggesting that the assessment design is flawed in taking what Newfield (2011) and others might describe as a ‘monomodal’ approach: I am simply drawing attention to the way that it differs from what takes place in the lecture theatre and the tutorial room. When I come to interview course tutors at the end of semester I might find there is a very good reason why measurements of understanding and ability rely on language in its different forms. For the time being however, I have three questions to reflect upon in the coming weeks and months:

Before that however I have a lecture on The Origins of the American Revolution. I expect there to be bullets, but no bullet points. References:

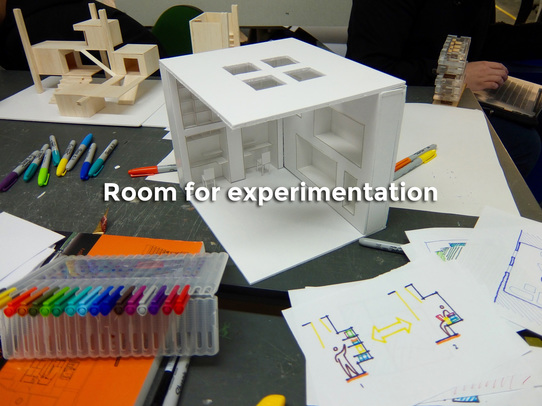

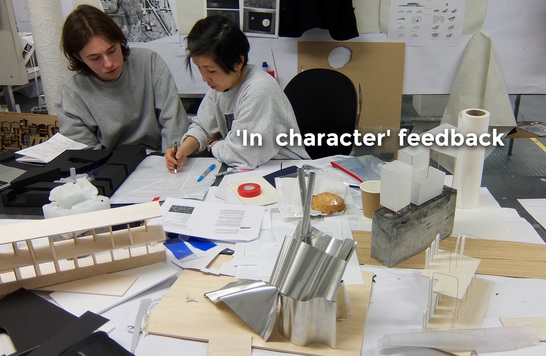

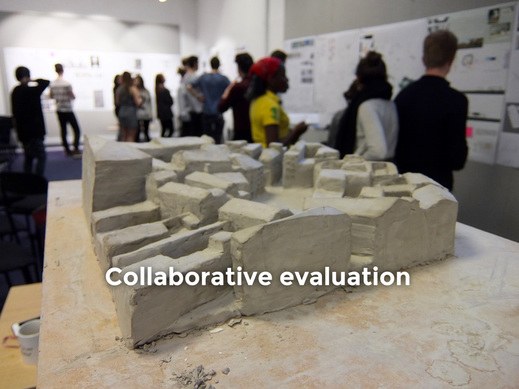

See also: Assessment, feedback and multimodality in Architecture Multimodality and the presentation assignment "I'm just glad it's not an essay!": a poster presentation assignment in music Between January and March this year I spent time in Edinburgh University’s Architecture School, observing a second year Architectural Design course. Over ten weeks I observed students and tutors involved in an assignment concerned with the design of a library. My interest was in learning how meaning was constructed and conveyed within a creative degree programme. In particular I wanted to gain insights into the ways that tutors and students approached an assessment exercise where work would be conveyed across a range of resources. Now that my ethnographic fieldwork has drawn to a close I have been invited to return to the Architecture School to share my findings. This has prompted me to spend some time thinking about what my experiences in the Architecture studio have to say about the relationship between multimodality and assessment and feedback within a creative setting. Looking back over my field notes and gathered photographs I have identified six themes which seem to stand out as being suggestive of the character of assessment and feedback in the Architecture Studio, as follows: A recurring feature of the Architectural Design course saw students being encouraged to explore relevant themes through drawings and models, which they would then bring to class each week. These artefacts would form the basis of tutorial discussion, where tutors and students would reflect upon the ideas being conveyed through the work. The environment was supportive and students were encouraged to use the preparation of these models and drawings as a way of experimenting conceptually with the design of their library building. At the same time, part of this experimentation pushed students to develop and refine their practical skills: my field notes describe how Maria had been investigating what happened to resin at high temperatures (it burned) and that Ellen had been exploring shape through the use of candle wax. Yet even at this formative stage there was encouragement from tutors towards nicely rendered sketches, polished architectural plans and accurate models: conceptual work and quality of finish. In this setting ‘risk free experimentation' did not mean ‘carefree’: students were encouraged to be ambitious and to bring new ideas and approaches to class, but that their creative energy should be directed towards the the acquisition of understanding and technique which would support their final coursework. This included thinking about the combination of resources that would be most suited to the ideas they wished to convey. This encouragement to be experimental was supported by feedback from tutors that was supportive and made use of dialogue that was in tune with the wider meaning-making rituals of Architecture. By 'In character' feedback I am suggesting that tutors engaged in a dialogue which displayed a symmetry with the approaches and artefacts that were the subject of discussion in class. For instance, when Jack (tutor) wanted to suggest an alternative way for visitors to circulate through Han's proposed library, he sketched directly onto his architectural drawings. Similarly, when Akiko (tutor) wanted Karen to think more deeply about the use of light in her proposed library, she took a pair of scissors and cut through her model to create a cross section that we could all peer into. In each case (and many other similar examples) this was accompanied by an oral commentary. Ideas were constructed and deconstructed using the same techniques for creating and conveying meaning - sketching, modelling, speaking - that students had used to develop their work and will be expected to use in Architectural practice. In the Architecture studio feedback is multimodal as well as in concert with the subject matter and the audience’s needs. From my fieldnotes, meaning was constructed and conveyed through: resin, acrylic, balsa wood, wire, wax, clay, plaster, card, wood, metal. Ink, paint, graphite. Ribbon, wool, netting. Light bulbs and scale plastic figurines. Hand-drawn sketches and computer-aided designwork. Photographs and architectural plans. Gesture, posture, eye contact. Voice. Space and silence. Printed type. Not all at the same time, yet always simultaneously drawing on a wide range of different resources (and more often than not, with words-on-page limited to playing a functional, descriptive role: ‘Scale 1:50’, ‘Elevation’). In the architecture studio meaning is constructed and conveyed in an array of richly multimodal ways, which in turn affects how tutors approach the task of marking assignments. Compared to 'essayistic’ assessment, the rich multimodality of the Architecture portfolio places a greater emphasis on acts of interpretation, rather than more straightforward measurements of quality. Although the marking of a conventional written essay requires the tutor to interpret what is being verbally conveyed, the existence of longstanding conventions around linearity, voice, argument and evidence lend a structure for evaluating the quality of ideas. The portfolio however draws on a combination of resources which speak with a less well articulated language (or indeed, range of languages). And whereas the essay has a pre-fixed format, the tutor evaluating a portfolio is challenged to interpret meaning from a collage of different materials, as the student composer has more freedom to bring her individual interests and talents to the fore. The tutor has to take account of how the different resources come together in concert or collision to create meaning. With a greater attention to freedom and interpretation, it is easy to see why tutors might not wish to work alone when it comes to evaluating and grading coursework... During the Review Lite exercise, students were divided into groups of three and then asked to circulate around the studio, reflecting on the designs being put forward by their peers. They jointly examined and discussed the ideas presented across the sketches and plans on display, before agreeing what they liked about the work and where they felt there was room for improvement. When it comes to assessing the final portfolios, tutors will work in pairs, moving around the studio and discussing how the presented artefacts sit in relation to the brief. In each of these examples the quality of ideas and work on display is evaluated through collaborative discussion between students or tutors. Through conversation and negotiation tutors arrive at an agreed position on how the collected models, sketchbooks and architectural drawings combine to address the assignment brief, followed by the grade that the work merits. When there is a high level of freedom in the representational form of the portfolio (for instance in the selection and use of materials and how they are configured in relation to each other) there would seem to be value in tutors working collaboratively to interpret and evaluate this highly multimodal work. As well as providing room for experimentation and opportunities for dialogue, the high level of student-tutor interaction during the Architectural Design course also seems to plays an important role when it comes to grading the student's overall work. Whereas in many subject areas, and particularly those which heavily privilege verbal communication, marking looks at the submitted work in a form of isolation or separation, a different approach exists in Architecture. In order to account for the learning that has taken place it is necessary to consider how students have approached the preparation of their work, the decisions they have taken and the paths they have followed. The normal university conventions surrounding anonymous marking are waived as tutors necessarily take account of the process as well as the final portfolio that is submitted for assessment. As one tutor described to me, the sketchbook can often be more revealing of the work undertaken and progress made by the student, than the curated final portfolio. If architectural drawings offer an incomplete picture of the learning that has taken place, the time spent together in class affords the opportunity to reflect on process as well as the final product. If we accept that meaning is socially constructed and shaped by cultural circumstances and personal histories, it would seem to make sense for tutors look to evaluate the quality of the work within, as opposed to isolated from, that situation in which it was produced. The six themes that I have described here represent an early attempt on my part to think about the relationship between multimodality and assessment & feedback within the Architecture Studio. Looking to the future I think it would be helpful to investigate whether the same approaches are a feature of other creative degree programmes. Before I do that however I will be sharing these findings when I return to the Architecture School next week. It will be interesting to see whether the Architectural Design tutors recognise the picture I have sketched of the meaning-making rituals that take place in their studio. With thanks to Douglas Cruikshank and the tutors and students within the Edinburgh School of Architecture and Landscape Architecture. Photographs were taken with the consent of the featured students and tutors. Pseudonyms have been used in the place of student names.

A flying visit to London to attend two sessions concerned with multimodality. Yesterday evening (14 April 2016) I visited the London Knowledge Lab for a meeting of the Visual and Multimodal Research Forum, followed today by Multimodality in Social Media and Digital Environments from the New Media Group of the British Association of Applied Linguistics, this time at Queen Mary University of London. My flight back to Edinburgh tonight is delayed so I’m filling the time by gathering my thoughts over an expensive coffee.

At the Visual and Multimodal Research Forum, Dr Elisabetta Adami, University Academic Fellow in Multimodal Communication at the University of Leeds, presented some ongoing research where she is taking a multimodal approach to investigate the experience of super diversity in Kirkgate Market in Leeds city centre. I had the chance to spend some time chatting with Elisabetta in the post-forum debrief where it emerged that we share a number of research interests. First, her work around understanding experiences of the Kirkgate Market isn’t so far from my own interest in how we can take a multimodal approach to understanding our relationship with the urban environment. Add to that Elisabetta's interest in multimodal assessment - she teaches a course on multimodality - and we had lots to talk about. And then today was dedicated to Multimodality in Social Media and Digital Environments where I presented the following paper about tutor experiences of multimodal assessment:

Judging by the conversations which took place over lunch, and the Twitter commentary that accompanied my presentation, my discussion of the ways that multimodality affects assessment seemed to strike a chord:

Now in brief summary - my flight has now moved from red to green on the Departures screen - here are three of the ideas that emerged most strongly from the different presentations, workshops and conversations over the last day-and-a-half.

Flight called. Coffee finished. The journey continues.

With thanks to Sophia Diamantopoulou (University College London), Agnieska Lyons and Colleen Cotter (both Queen Mary University of London) for giving me the chance to attend the sessions described above.

To set the scene, we can describe any presentation or public speaking occasion as a multimodal event in the way that it draws on a range of different semiotic resources to communicate meaning. In fact the presentation setting would seem to be a very effective enactment of Carey Jewitt’s description of multimodality when she proposes that:

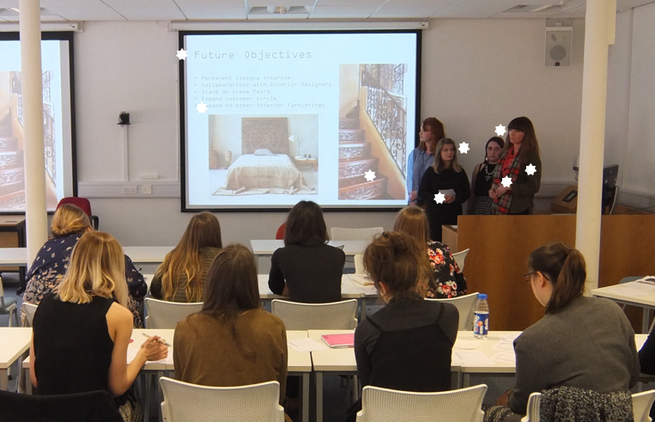

This is illustrated in the annotated photograph below, capturing one of the project teams pitching their proposed textile range. Each of the stars in the image represents what we might understand to be a mode, all with their own ‘special powers and effects’ (Kress 2005, p 7) when it comes to the communication of meaning. This includes (but is not limited to) gesture, posture, eye contact, language (written and spoken), image and so on. From there we can go on to look at the meaning carrying potential of typeface, colour and layout within the visual realm, before turning an ear to the signifying power of pitch, volume and tone within the oral dimension. That the different modes are represented through stars is in line with the conceptualisation of multimodality as a 'constellation’ of different resources within a single communicational event (see for instance Carpenter (2009), Flewit et al. (2009) and Merchant (2007)). 'About more than language': Textile Design students use a full range of communication resources to convince us to invest in their bespoke flooring. Looking at the assessment criteria for the presentation exercise, students were encouraged to think about how they could communicate their ideas orally (how they spoke), visually (the content of their PowerPoint slides) and also physically (eye contact and smiling, for instance). Marnie explained to me that the criteria build upon her own professional experience as a textile designer, and recognise the need for her students to "stand up and defend their work in front of clients" in the future. This immediately reminded me of the work of Kimber and Wyatt-Smith (2010) around multimodal assessment, where they emphasise the need for assessment practices to 'authentically' encourage the development of skills that young people will need when they enter the workplace, which includes the ability to think and work creatively. Of course, multimodality is not simply concerned with documenting the different meaning-making resources that are at play, as my annotated image has started to do. As the latter part of Carey Jewitt's definition highlights, we are also interested in the relationship between these different modes, which in turn shapes how meaning is constructed and conveyed. When a presentation is delivered we are influenced by what is said (the words), but at the same time how it is said (pitch, tone and volume for instance) , the accompanying use of body language, the supporting visual content, what the presenter has chosen to wear and other resources that each carry meaning. As an audience we then interpret our own meaning from the combined effects of all the different resources. Consciously or subconsciously, our interpretation might be shaped by how all the different resources cohere (good!) or collide (probably bad). Therefore within a single communicational act - such as a presentation - the different modes sit in relation to each other, not in isolation. With this in mid, to the earlier constellation diagram we can now add all these different lines of interaction, emphasising how the 'inter-modal synergy' as I'm calling it, generates meaning. Inter-Modal Synergy or The Celestial Plough meets Tron To bring this back to the presentations taking place in the Textile Design class, the work I found most convincing was by a team who seemed to have spent time considering how they could convey a message of professionalism through all the different communicational modes stipulated within the assessment criteria. Their oral delivery (spoken 'in character'), the design of their slides (attention to layout, font and white space) and use of physical communication (eye contact with the audience, open body language) seemed to weave together into a single coherent message: "We're serious about this work...now trust us with your money." In contrast, on other occasions the use of spoken language was sometimes out-of-step with the quality of ideas being conveyed within the slides, for instance when a group opened their presentation by asking “Should we introduce ourselves, Marnie?” The spell was broken and I was reminded that I wouldn't, after all, be investing in colour-changing brollies, chic children's clothes or any of the other fabulous ideas that were put forward on the day. Returning for a final time to Carey Jewitt's articulation of multimodality, it is also a useful way of looking at what was not present within the student presentations. Whilst recognising the limitations of what can be achieved within a timed five-minute presentation, and the need to satisfy the stipulated assessment criteria, none of the groups exploited the space of the room as a resource (which Jewitt has elsewhere pointed to as a modal resource, for instance through the ability of teachers to enact power relations by walking around the classroom). At the same time, the tactile qualities of the different products remained trapped on screen. Even though it wasn't anticipated in the assessment criteria, and was perhaps even deemed surplus to requirements bearing in mind the background of the wider audience, I wonder whether teams might have come over as even more assured if they had stepped away from the computer terminal to hand us examples of the textiles they intend to use. Perhaps, though, this is being saved for the assessed exercise next week when the teams will present their wonderfully colourful, creative and multimodal work 'for real'. With thanks to Assistant Professor Marnie Collins and her BA Textile Design students. References:

CARPENTER, R. 2009. Boundary negotiations: electronic environments as interface. Computers and Composition. 26, 138-148. FLEWIT, R., HAMPEL, R., HAUCK, M. and LANCASTER, L. 2009. What are multimodal data and transcription? In The Routledge Handbook of Multimodal Analysis. Jewit, C. (Ed) (London, Routledge): pp. 40-53. KIMBER, K. & WYATT-SMITH, C. 2010. Secondary students' online use and creation of knowledge: Refocusing priorities for quality assessment and learning. Australasian Journal of Education Technology, 26, 607-625. KRESS, G. 2005. Gains and losses: new forms of texts, knowledge and learning. Computers and Composition. 22(1): pp. 5-22. JEWITT, C. 2009. An introduction to multimodality. In The Routledge Handbook of Multimodal Analysis. Jewit, C. (Ed) (London, Routledge): pp. 14-27. MERCHANT, G. 2007. Mind the gap(s): discourses and discontinuity in digital literacies, E- learning, 4 (3), 241-255.

Over the last six weeks I have been undertaking participant observation in the Edinburgh School of Architecture and Landscape Architecture (ESALA) as I have sought to understand how students construct and convey meaning through their design work. This exercise is the subject of an assignment I am completing for an Ethnographic Fieldwork course, whilst at the same time being of direct interest to my Doctoral research where I am investigating multimodal assessment in higher education.

During each visit I spend time observing students as they work on the design of a library building. For the most part my notes have been in ‘text’ form (typed onto my laptop), supported by photographs of models, sketches and other examples of student work. These fieldnotes have worked up to a point, however they haven’t managed to recreate the atmosphere in the design studio: they are muted both figuratively and literally. On my most recent visit to the design studio last Friday, I decided to complement the gathering of words and images, with sounds. To do this, I walked the length of the studio (and then back again) recording sound through the voice memo function on my phone. I wasn’t interested in recording full conversations, but was instead keen to capture the traces of laughter, music, dialogue and other sounds which contribute to the ambient personality of the studio. The subsequent task of ‘writing up’ my notes later the same day also called for a different approach from normal, as I pulled together a short video combining a representative range of audio and images, juxtaposed with extracts from my typed notes. This is what I came up with:

I think the orchestration of images, sounds and words has enabled me to represent the colour and vibrancy of the architecture studio in a way that I wasn’t previously able to achieve. I think this multimodal approach to data gathering and representation offers something different to the conventional monograph with its heavy privileging of words on page. That said, gathering and interpreting visual and aural data presents its own challenges - both practically and critically - and we should remember that photographs and sound recordings are neither neutral nor an accurate recreation of reality. Nevertheless, in light of Architecture’s interest in a wide range of semiotic materials, I wonder whether an ethnographic approach which pays due attention to the aural and visual, is a more apt way of investigating how knowledge is constructed and conveyed in the design studio.

see also: A creative approach to demonstrating success Urban flânerie as multimodal autoethnography Tomorrow morning (Thursday 15 January 2015) I will jointly deliver a conference paper on Urban Flanerie as Multimodal Ethnography, with my colleagues Jeremy Knox and Michael Sean Gallagher. The occasion is the Multimodality: Methodological Explorations conference at the Institute of Education/University College London. The main thrust of our paper will be that we can better understand urban space by stepping into the shoes of the Flâneur, and then setting out to capture and then convey the sights and sounds we experience as we wander through the city. To make this argument, we will spend today, the day before the Conference, enacting our proposed methodology within the EC1 postcode of London. What we’re interested in doing is exploring how the collection and then the multimodal communication of data might enable us to ask questions about the character within a particular snapshot of time, as well as our own relationship with urban space. Beginning at 10am, we will wander the streets of East Central London, taking photographs and recording audio of anything that talks to us about personality of this part of the city. Following in the path of the Flâneur, we don’t have a set route in mind, or the intention to visit particular buildings, parks or pubs. Instead our wanderings and therefore our data collection will be shaped by a left turn here, an interesting alley there, a blocked-off pavement, an enticing cafe, the weather, and so on.

Once we have tired of walking the streets, we will sit down, download and then trying to make sense from our gathered visual and aural data. We will then decide how we might combine all the gathered sights and sounds into a meaningful, multimodal artefact. After that we will reflect on the methodological significance of our exercise. And then tomorrow morning we will present the same conclusions – and the artefact – at the Conference. The tight deadline presents this as a risky approach and it could end up being a late night (but then, we'd need to fill our evening in central London somehow). We feel though that it's a useful way of testing our methodology in a practical way. Assuming we pull this off, we feel there is the potential for this approach to be used within different learning situations, which is something we hope to discuss tomorrow morning. For now though, it's time to gather our cameras and coats and to step out into the cold of EC1.

Earlier this year I spent a day in the company of Michael Sean Gallagher, Jeremy Knox and Philippa Sheail as we set out to undertake a loosely structured day of multimodal data collection in Edinburgh. Michael, Jeremy and Philippa were all due to contribute to the Networked Learning Conference taking place in the same city in the days that followed, while Michael and I would separately be delivering a session about multimodality and digital learning spaces for an online tutoring course at Edinburgh University. Rather than taking time to make final changes to our respective presentations, we instead agreed to take part in what we vaguely described as a ‘multimodal mapping exercise’.

We weren’t exactly clear what we hoped to achieve, other than to try and collect a range of data that somehow captured a sense of the city during the specific period of time that we experienced it. On reflection, the notion of ‘experiencing’ a city seems overly passive and I wonder whether ‘enacting’ might be a more useful description of our approach. Irrespective, our intention was to wander the city in a way that avoided Tourist Guide Edinburgh in favour of capturing a multimodal snapshot of everyday life. What this meant in practice was that wherever we stopped within view of what might be regarded as a site of beauty or historical interest (and to be fair, Edinburgh's a good looking city), we would search for the untold stories to be found in the street furniture, graffiti and general detritus of our surroundings.

Actually, that's an incomplete way of describing how we tried to get a sense of our surroundings in that it ignores the soundtrack that accompanied and shaped our journey under bridges, through closes, into bars and restaurants, and to other neglected corners of the city. For instance, the sound of an industrial extractor fan within Greyfriar's Churchyard seemed incongruous and therefore significant. I imagine that when feature films use this location, a runner would be dispatched to the adjacent pub to plead with the kitchen staff to switch off the industrial-scale appliance. For our own purposes however, it felt important to capture how the industrial clashed with the picturesque, as if those at rest sleep to the white noise of machines.

On a technical level, we used a range of devices for the purpose of capturing data: iPhones, iPad and a camera. Strong coffee and Tunnocks Caramel Bars also helped our field research in a less direct way. My pen and notebook remained unused, although in hindsight it would have been helpful as a way of recording the specific sites of data collection. That said, Michael usefully tracked our progress using the Trails app. As well as offering a reminder of the specific path we followed, by the time that Michael's iPhone drained of power, the Trails read-out told us that we'd explored more than 14km of Edinburgh's pavements, parks and public houses. With a little more planning we could probably have borrowed some devices that would have produced a better standard of visual and aural material, however I'm relaxed about the mixed quality of what we captured. In fact, perhaps a snapshot shouldn't be too polished: the flaws in the sound clips and photographs in themselves reflect the imperfections of the city.

Reflecting the wider approach to this exercise, by the end of the day we didn't have a clear plan of what we would try and do with the collected data. Thus, over late night food and last orders it was decided that we would each set out to remix the data in our own way. Quick off the mark, Michael blogged about our exercise within days and has since created a multimodal video postcard. It has taken me longer to settle on an apt way of capturing a sense of the city as I've toyed with a few unsatisfactory and uninspiring representational forms. In hindsight, I've been guilty of over-thinking how I might place the modal fragments onto on a digital canvas (and what form this canvas might take), not least as this considered approach was at odds with the haphazard and unrestricted way in which we approached the exercise itself.

What I opted for, as seen and heard here, is an interactive map and an accompanying aural compilation (as well as this text-based commentary). It was important that the audio was experienced concurrently with the map: after all, if we understand multimodality to be concerned with the simultaneous juxtaposition of a range of modes within a single communicational act (and I'm borrowing from Kress and from Jewitt here), then the aural and visual components needed to be configured accordingly. And of course, we didn’t experience Waverley Station with the volume turned down and therefore neither should you.

Looking and listening to the presentation of data here, I think I've created an accurate if incomplete record of how we enacted everyday Edinburgh on Sunday 6 April 2014. The images, sounds and words offer a flavour of the city but can't capture the taste and smell of the IPA or 80 Shilling, or adequately account for other sensory experiences that shaped our engagement with our surroundings. Nevertheless, our focus on detail and detritus tells stories about Edinburgh that, I think, are ignored in the conventional narrative of Scotland's capital.

For instance, the prospective undergraduate student might be less interested in the opening hours of Holyrood Palace than the fact that, at the bottom of Blackfriar's street, equidistant between the University's School of Education and the Cowgate's sites of late night revelry, is a place to access the Internet whilst enjoying a late night kebab. On Infirmary Street meanwhile, an innocent house number has become a battleground for a generations-old political conflict. As far as we could see, nobody had been defacing the city in the name of the pioneers, writers and thinkers that are more commonly and conventionally celebrated in Edinburgh's story (although we did question how David Hume might feel about the damage done to city's skyline in his name). Our focus on the everyday is a useful reminder that Edinburgh is understood through parking tickets as well as concert tickets. And for every Michelin Star there are a thousand takeaway restaurants that keep the people active and unhealthy, spreading a trail of discarded plastic over the ancient, cobbled stones of this beautiful city. James Lamb, 10 May 2014 |

Search categories

All

I am a Lecturer in Digital Education (Education Futures), within the Centre for Research in Digital Education at The University of Edinburgh.

@james858499 [email protected] |