|

Later today I will be contributing to Making Research Visible, an event organised by the Research and Knowledge Exchange Office here at Edinburgh University. The aim behind the day is to explore the different ways that we can think about the accessibility and visibility of our research, for instance through social media. My input will be to talk about the process behind the video I created for the Manifesto for Teaching Online. I will argue that we can raise the profile of our work by presenting it visually. This is the video:

and here are the slides I will present this afternoon:

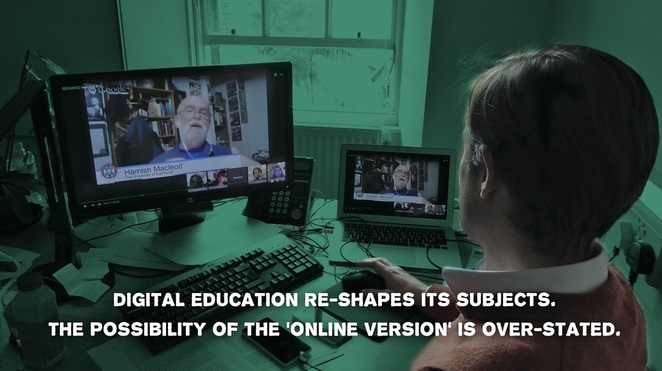

The portability of the video format, combined with the ability to convey a considerable about of content within a short space of time, allows us to extend the reach of our academic work, for instance through the sharing capacity of social media. In my presentation I will also describe how the medium provided an opportunity to match the representational form of the video with the following Manifesto statements, thereby enacting and advancing the same arguments:

Text has been troubled: many modes matter in representing academic knowledge

Remixing digital content redefines authorship

Arguing for the value of visually-mediated research does not mean dispensing with more conventional printed ways of sharing our research. Neither does it mean that the visual form will always be an appropriate way of sharing academic knowledge. All the same, in our increasingly networked and visually-mediated world, the video format is increasingly in-tune with increasingly multimodal literacy practices and representations of academic knowledge.

See also: Manifesto for teaching online: reaction!

0 Comments

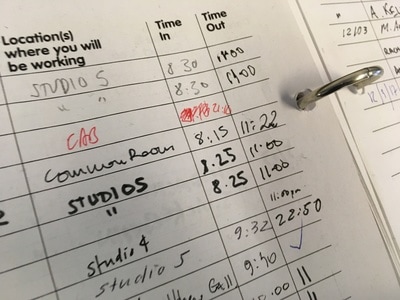

Next Tuesday (6 June), I will spend the day Exploring Visual Methods as a Developing Field, as part of an ESRC summer school taking place at Edinburgh University. Ahead of the event, which will be delivered by Professor Kate Wall from University of Strathclyde’s School of Education, participants have been asked to take 15 photographs which represent what we think it means to be a Doctoral student in 2017. From that we need to select a sub-set of 5 photos that best address the enquiry. Here is what I will be taking to the session: This photograph is intended to reflect how my research depends on both physical and online spaces and communities. My 'network' is made up of colleagues on campus who are also part of a larger dispersed group of researchers and lecturers, many of whom I have never ‘met’ beyond our exchanges in Twitter and in other digital settings. At the same time I am as likely to be talking about my research online, as on-campus. Something I really value about being a PhD student is having the flexibility to choose and move between different spaces that I think will support to the task I am working on at a particular time. The Psychology building on George Square is a good space to spend an hour of interrupted writing. Others locations on campus (and beyond) are better for reading, others for conversation, and so on. I usually begin each day with a plan of where I will work, depending on what I need to achieve. Edinburgh is full of pleasant and inspiring place to work. I'm lucky. This is my PhD supervisor, Sian Bayne, on a billboard outside Old College. There are a few of these posters dotted around campus and more than once they have reminded me that I owe Sian a piece of writing. Subliminal supervision. I have included this picture to represent how the expectations and direction set out by Sian and my second supervisor, Jen Ross, guide my research. If some of the other photographs here point towards the independence that comes with being a PhD student, it is accompanied by guidance and the encouragement to work to a high standard. This external hard drive represents the data I have collected over the last year whilst carrying out ethnographic field work. It contains thousands of photographs, hundreds of sound recordings and quite a lot of words. Most recently I've been adding lengthy interview recordings which had been exhausting my laptop. This image sheds light on the subject of my research, but also talks about the way that so much of my work is captured and condensed into ones and zeroes. My doctoral research takes place alongside other interests, activities and responsibilities. Before taking this picture I had been checking e-mail whilst my son had his breakfast. We were listening to music and talking about how long it would take to walk to the moon. After that it’s a rush to get out of the house before 7.45am. It felt important to include a photo which made the point that doing a PhD is never just doing a PhD. The possibility of attending evening seminars, travelling to conferences, taking advantage of study exchanges and other opportunities always depends on more than whether these activities match my research interests or if they justify the cost or time (and I'm not suggesting this is unique to me, of course). Here are the other images, meanwhile: Returning to the instructions for this exercise, we have been asked to print out the photos in order that they can be shared as part of a group exercise: it will be interesting to see how my own experiences of doctoral research sit along those of a wider group. Fascinating exercise, not least as I've been using image elicitation in my own research. Looking forward to it.

See also: Digital sociomaterial journaling Looking beyond photos: the architectural site visit The visual, multimodal History classroom Over the last year I have taken thousands of photographs whilst observing students and tutors from Edinburgh University's Architecture programme. At the beginning of this exercise I was mostly interested in recording what took place directly around assessment: preparing the portfolio, presenting work in a review exercise, practices around marking and moderation. Over time though I have sought to capture a broader range of phenomena as I have looked towards sociomateriality as the critical lens for my Doctoral research. From initially focusing on the meaning making rituals of students and tutors around assessment, I have instead been looking to the ways that knowledge construction in the Architecture studio is a more complex entanglement of human, technological and other material interests. Or as Fenwick and Landri describe in their work around sociomaterial assemblages in education:

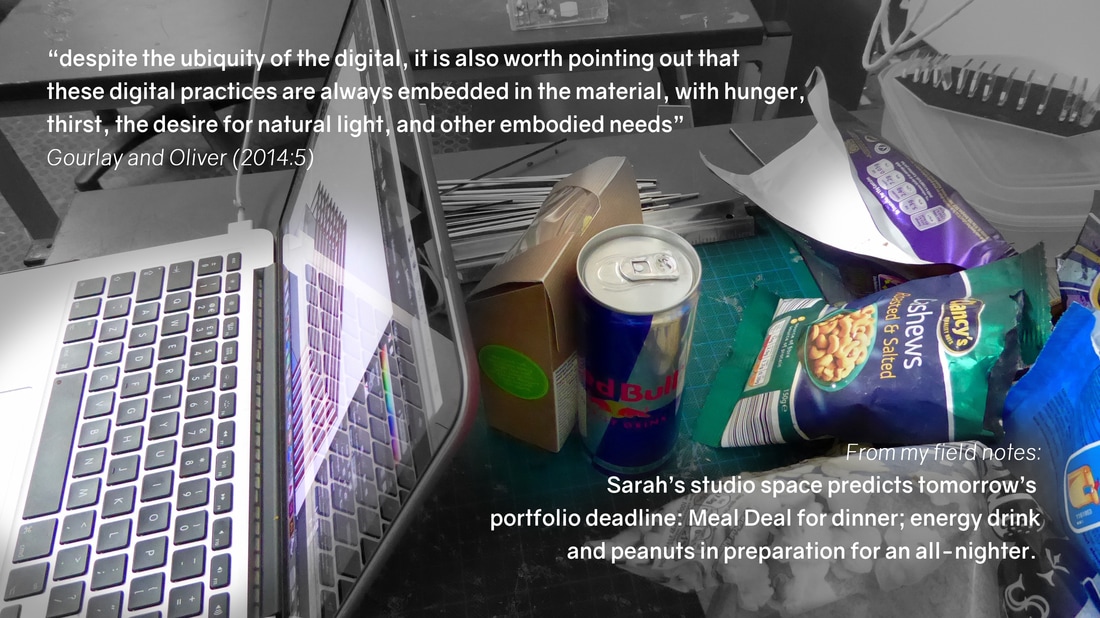

If I was initially guilty of viewing assessment in an overly simplistic way, as a fairly clear-cut exchange between student and tutor, sociomaterial critiques of education have instead encouraged me to examine the messy reality of what takes in and around the classroom, where 'learning is embedded in action and emerges through practice, processes that produce the objects and characteristics of educational events.’ (Knox and Bayne 2013). In this way assessment can be seen as a performance that depends on the student and tutor, but also looks to the role of curriculum, technology, sound, light, clothing and other visible and invisible actors within an evolving pattern of materiality (Fenwick et al 2011:8). What this has meant in practice is that, as well as continuing to photograph students and tutors in the Architecture studio, I have pointed my camera down at the floor and upwards to the ceiling. I have crawled under desks and balanced on chairs. I have photographed and recorded the sounds of ventilation shafts, data projectors, corridor conversation. I have attracted troubled glances from students unfamiliar with my research. Without having yet commenced my analysis of the gathered data, a recurring theme to emerge from my photographs and also my written field notes, is the way that food and drink seem to be an integral part of what takes place in the studio. Alongside the more recognisable tools of the architecture student we find snacks: pencils next to a packet of peanuts; chocolate alongside cardboard; Rhino with Red Bull. click on image to enlarge Through the image above I have tried to show how my field notes and photographs resonate with some of the principle ideas around sociomateriality within education, in this case echoing work by Gourlay and Oliver (2014) where they offer a sociomaterial account of digital literacy practices:

For the purpose of further illustration I have included below a small selection images which would seem to reiterate Gourlay and Oliver's call to remain alert to the way that our use of digital resources in education, for instance around assessment, is always and inevitably entangled with a much broader range of resources, influences, limitations and opportunities beyond the interests of the assignment task. click on images to enlarge References

See also: Digital sociomaterial journaling Camera, recorder, scissors, brush: ethnography in a pop-up exhibition Architecture, multimodality and the ethnographic monograph

As part of the series of events organised by the Centre for Research in Digital Education at the University of Edinburgh, I recently (18 November 2016) organised a walking seminar through Edinburgh's Old Town. Along with my colleague Jeremy Knox, and joined by participants from inside and beyond the university, we undertook an unscripted excursion where our path through the city was shaped by our varying personal interests as well as the digital mobile devices we brought to the exercise.

Our activity can be situated within the growing critical interest in urban walking (Richardson 2015) as well as the tradition of walking ethnography (Vergunst and Ingold, 2008). Going back further, this type of unrehearsed excursion has its roots in the flânerie of Walter Benjamin and later the dérive of Guy Debord and The Situationst International. By moving our seminar beyond the physical boundaries of the university we dispensed with the abstract or agenda that often lend structure to on-campus conversation, instead inviting participants to bring their own research or professional interests to the exercise. We imagined that the excursion would be of interest to colleagues concerned with digital culture and mobile learning (see for instance Sharples et al. 2007) and those with an interest in how we construct meaning from our surroundings, for instance through sensory ethnography (Pink 2011), multimodality (Kress and Van Leeuwen 2001) or a sociomaterial sensibility (Fenwick, Edwards & Sawchuk 2011).

Across the duration of a lunchtime we walked and talked, sharing our interests, ideas and observations with our newly-found colleagues. At different locations that we broadly agreed to find interesting, we paused to capture our experiences on our mobile devices. This included the gathering of images and audio recordings, some of which are gathered together in the short video that offers a more rich and evocative record of what took place than I would have been able to offer through words.

Photos by Nick Hood, Hamish MacLeod and by me.

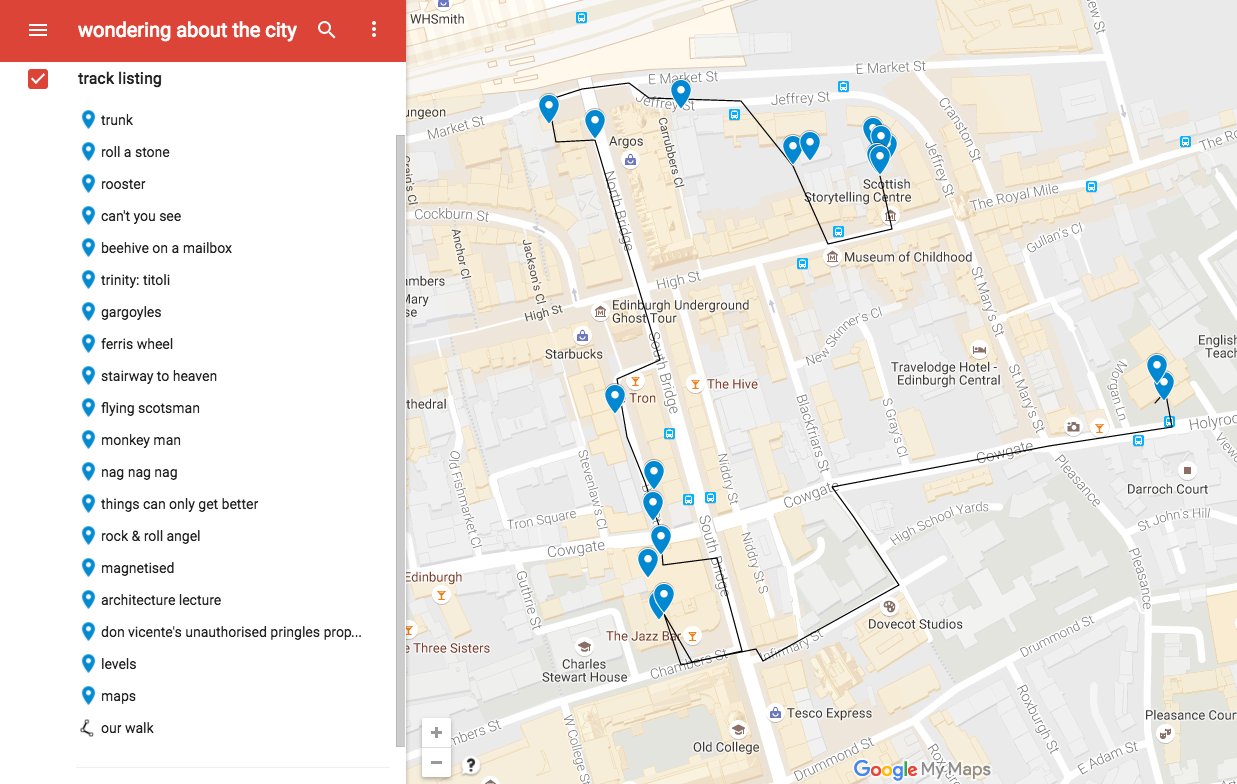

Another alternative and imaginative way that technology merged with our trajectory across the Old Town was provided by my colleague Jen Ross, where she compiled a live playlist on Spotify, triggered by her surroundings at different stages of our journey. Members of the group were drawn to Jen's approach and in turn suggested search terms for what became a collaborative playlist. Jen has since mapped the different songs onto the corresponding locations within an interactive Google map. The compiled playlist and map are worthy of space in their own right, however this screengrab presents an alternative way of representing our walk.

The different digital artefacts to have emerged from the excursion - video, music playlist, interactive map - go some way to reflecting the varying interests that participants brought to the exercise. At different times during our walk conversation turned to whether and how we felt this type of exercise might be used in different educational settings. Emergent ideas included:

In the days following our walk my colleague Christine Sinclair used ideas and images from the exercise as a way of encouraging students to reflect on the nature of space and place within the Introduction to Digital Environments for Learning course on the MSc in Digital Education. At the same time I am intrigued by the suggestion that this type of activity might help to break down the "clusters" that can form in university programmes where students from the same international communities group together, meaning that they miss out on what might be learned from their peers and their experiencing of the city beyond the vicinity of the campus. When Michael Sean Gallagher, Jeremy Knox and I first talked about the idea of enacting digital urban flânerie we were keen that, alongside a possible conceptual contribution, our methodology might be adopted and adapted into practical learning activities. Looking back on the excursion through the Old Town, I think there's mileage in this kind of activity. References:

See also: Multimodal dérive in Amsterdam Leaving do/Edinburgh Old and New EC1 (Sights & Sounds)

What follows is a short video that gathers together images and sounds I collected around a pop-up exhibition by second year Architecture students. As I have explained elsewhere on this blog, I currently spend every Friday in the Edinburgh School of Architecture and Landscape Architecture where I observe students and tutors as they participate in teaching, learning and assessment. This ties in with my Doctoral research into multimodal assessment across the disciplines.

Across five hours last Friday (14 October) I made dozens of sound recordings and took hundreds of photographs as students set up the gallery, arranged models for display and finally attended an exhibition of their own work, where they were joined by tutors and other members of the architecture school. The work on display comprised more than 2000 models constructed over the first five weeks of the Architectural Design course. Situating myself in the gallery for the afternoon I was able to observe the small archipelago of buildings sprawl into a city-in-miniature, with a broad panorama of approaches and imagination on display. The quality of work can be seen within the images in the video, but is also heard in the excited laughter during the exhibition of work: listen carefully and you might hear a student expressing how proud she is of what the group had achieved.

Through the gathering of aural and visual data I wanted to make a record of the pop-up exhibition that would inform my research: a piece of video ethnography to represent what would have been hard to achieve through written description or images-in-isolation. In the unrehearsed setting of the pop-up exhibition however I was thrust into the role of general exhibition helper. As I swept the floor and cut display paper down to size I gained a better appreciation of what was taking place than would have possible had I sat on the outskirts. If the ethnographer’s main instrument is him- or herself, in this instance it was accompanied by camera and audio recorder, brush and scissors. See also: Architecture, multimodality and the ethnographic monograph Looking beyond photos: the Architectural site visit Listening to the street

For the duration of this semester I am spending every Friday in the Edinburgh School of Architecture and Landscape Architecture, observing students and tutors involved in an undergraduate course in Architectural Design. This ethnographic study mirrors my fieldwork in an American History course where I'm observing tutorials and lectures, all in support of my Doctoral research into multimodal assessment across the disciplines.

Each visit to the Architecture School begins a little before 9am with a meeting of the course tutors. They discuss teaching, assessment and other aspects of the course. There is coffee, conversation and a passionate commitment to subject and students. After that the tutors make their their way to the design studio to meet with their groups. The studio occupied by these second year undergraduates achieves the effect of feeling subterranean without in fact being below ground: as one of tutors ruefully put it when attempting to sell the space to her group: "There's a window at the far end - make sure you all get a chance to look out of it." From the uneducated perspective of the observer, the creativity and imagination demonstrated in the models, sketches and other examples of student work sits in stark contrast to the seemingly drab and claustrophobic studio space in which they are constructed or displayed. It is something of a relief then that studio time is interrupted by excursions out of the Architecture building. So far this has included a visit to the Fruitmarket Gallery to see an exhibition by Damian Ortega ("To get you to really think about how you present your work in the studio" as a tutor introduced the exercise) and more recently by a site visit to King Stables Road in the heart of Edinburgh. The purpose of the visit to King Stables Road was to introduce students to the site for the architecture school they will design for their assessment exercise this semester. The group I followed were encouraged to spend time experiencing the environment that will be central to their thinking in the coming weeks and months. As we assembled in the shadow of Edinburgh Castle, the tutor encouraged the group to go beyond merely taking photos and to include time for discussing and reflecting upon what they experienced, in order that they would be able to make a visual, emotional response to the site ahead of the following week's tutorial. For the purpose of my own research I used my iPhone to gather some of the sights and sounds of the exercise, as the group navigated its way around the puddles, discarded wine bottles and polystrene takeaway detritus of King Stables road. I have collected the recorded images and sounds together within this short video:

While the video does the intended job of providing me with a record of the site visit, what it fails to do is adequately take account of the wider experience of the excursion, or the atmosphere in that particular corner of the city. This would seem to echo the tutor's instruction for students to talk and think about their surroundings, rather than rapidly traversing the site whilst gathering photos for later consumption. This emphasis on critical reflection-whilst-walking reminds me of the work of Dicks et al. (2006) where they introduced and critically considered the possibility of multimodal ethnography. Drawing on research where they investigated communication and meaning-making within a Science visitor centre, the authors reflected on the opportunities and limitations of gathering visual data, including photographs and video recordings. While these digital visual approaches were able to go beyond what it was possible to record using conventional field notes, they were insufficient in themselves to take account of movement and the materiality of a space. In response, the authors took to walking through the Science visitor centre in order to experience its ‘physical flow’ and ‘living, material, kinetic environment’ (2006:87).

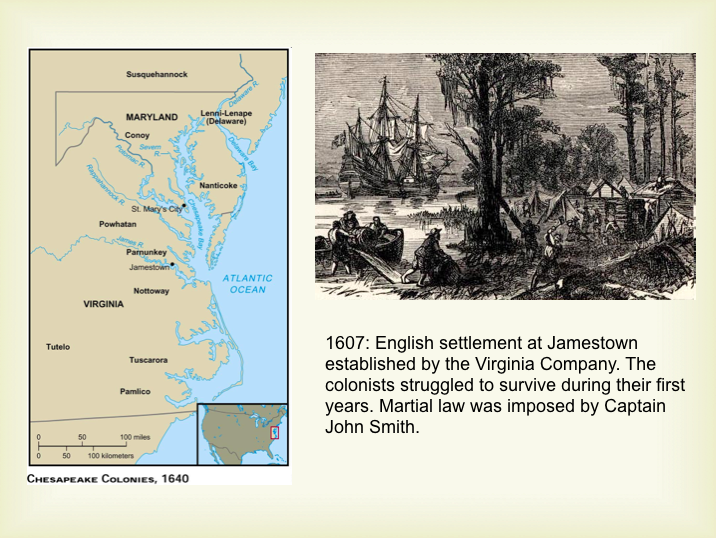

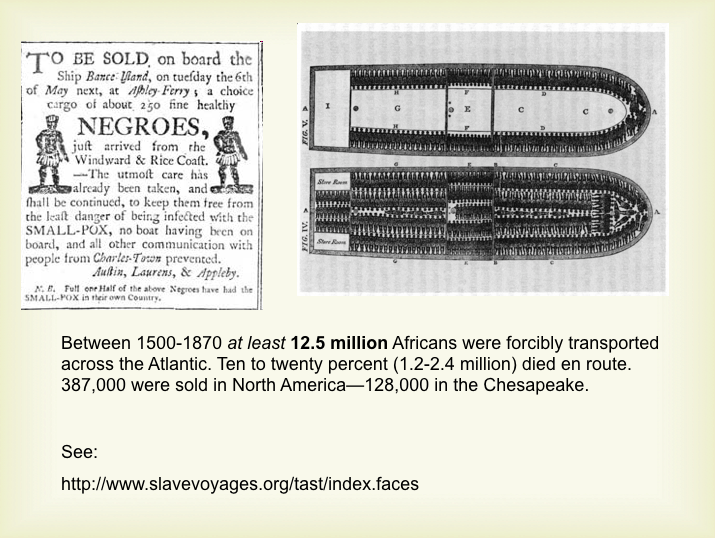

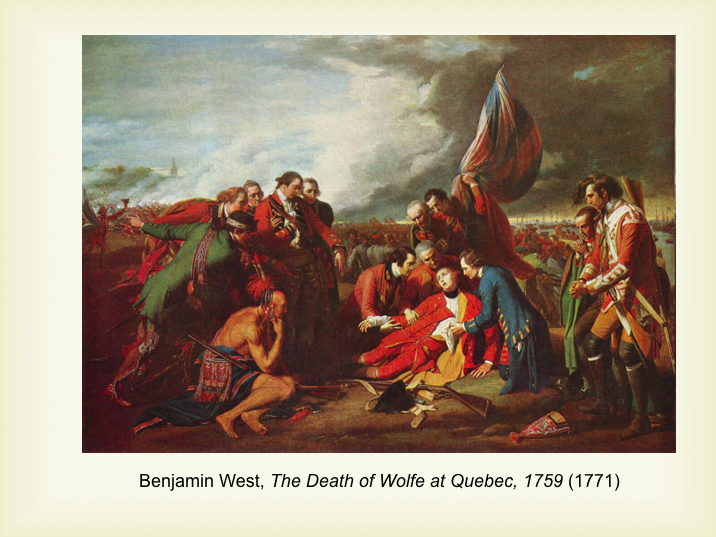

As the architecture group made its way around the perimeter of the King Stables Road site all of the dozen students took photographs to a greater or lesser degree. In some cases this was augmented by making sketches, peering over walls and pausing to point out different aspects of the site. On another occasion around half of the group stopped for several minutes to variously take in the scene and enter into conversation. In this instance (which is seen and heard in the final photos in my short video), I would suggest that the students went beyond the gathering of photos to think about constructing meaning in-the-moment. Their gathering of photographic representations of the site was interspersed with discussion and then moments of silence as they seemed to reflect on what they could see, hear and feel around them. Perhaps the conclusion to draw here is that although photographs and video recordings provide a useful way of representing particular qualities of our surroundings, they cannot do justice to the sensation of being hit by water dripping from an overhead archway, or of the distinct aroma of last night's discarded take away and tonic wine. Reference: Dicks B, Soyinka B and Coffey A (2006) Multimodal ethnography. Qualitative Research 6(1): 77-96. See also: Multimodal dérive in Amsterdam Listening to The Street As part of my Doctoral research into multimodal assessment in the Humanities I am undertaking an ethnographic study of an undergraduate American History course. I observe lectures, tutorials and other situations where students and tutors gather to construct meaning, as they explore The Making of the United States of America. There are two reasons I wanted to spend time in a History class. First, in common with the majority of Humanities courses, assessment within History programmes tends to privilege language, commonly in the form of the essay. Second, with its interest in visual artefacts as a means of study - drawings, paintings, maps, photographs - History has an eye for the way that images contribute towards understanding. Bringing these two ideas together, I wondered whether History programmes might be open to assessment practice where attention is paid to the visual, multimodal character of student work. Now that I have reached the third week of the History course (and have a couple of hours before the next class), I am recording some early observations about the role that images have played within classroom teaching. To begin with some context, this is a second year undergraduate course drawing students from a range of degree programmes. Three times a week the lecture theatre is packed with an audience of around 300, augmented by tutorials with groups of around 12 students each. In all of the classes the tutors have used PowerPoint presentations, with images to the fore. Something that really stands out from my field notes is that these images are always more than a backdrop: they appear central to the knowledge that the tutor wishes to convey. For instance:

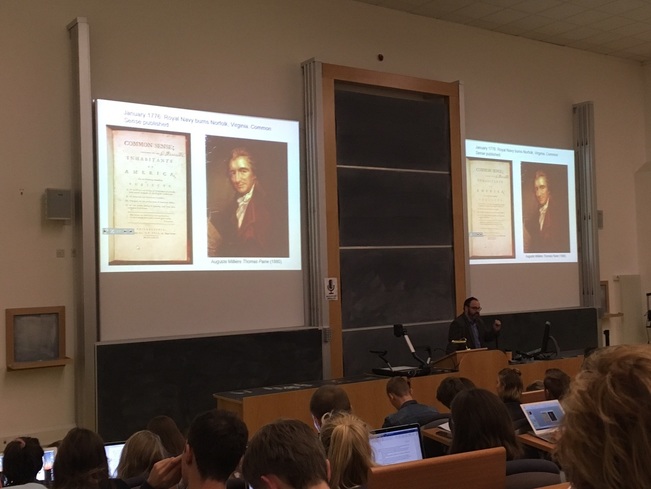

In these instances the images work alongside the oral delivery, adding colour and context to what is being said. This isn’t to suggest say the lecturer’s oration and wider performance is presented in monochrome: on the contrary it is enthusiastic and eloquent. Simply, the images are vital in helping the tutor to convey meaning. Click on images to enlarge. Slides reproduced with kind permission of Professor Frank Cogliano. On other occasions the images are themselves the central focus of study. Cartoon depictions of individuals and events are used to prompt students to reflect on competing perspectives and attitudes of the time. Newspaper adverts and notices, variously drawing attention to slaves-absconding-or-for-sale, are themselves historical artefacts that demand discussion within the tutorial setting. For the most part the images on screen are accompanied by reasonably small bursts of text (typed words), mostly single sentence captions providing factual information: title, subject, author, date and so on. Three weeks into the course and I have yet to face down a single bullet point. In terms of both prominence and placement, text immediately seems to perform a functional supporting role to the central positioning and critical purpose of the image. This however disregards the presence of text within many of the images: a political proclamation or newspaper notice may be presented in j-peg format however the conveyed meaning is heavily dependent on the use of text. If we narrow our gaze from the slide in its entirety to instead see an image as a communicational act in its own right, we become aware of the intricate assemblage of meaning conveying resources sitting in juxtaposition: text, font, colour, spacing, layout and so on. When this is combined with the tutor’s oral delivery (volume, tone, pitch, pace, silence) and physical performance (eye contact with the audience, gesture, posture, movement across the space behind the lectern) we see that the History classroom is richly multimodal (or ‘densely modal’ to borrow from Norris (2004)) in the way that meaning is conveyed and interpreted. Picturing Thomas Payne in the richly multimodal History classroom In contrast to the highly visual and multimodal character of meaning-making in the classroom, assessment for the American History course privileges the use of written language. Coursework comprises two conventional essays while 20% of the final mark is based upon a ‘practical examination’ in the form of a student’s contribution towards tutorial discussion. To be clear, I am not suggesting that the assessment design is flawed in taking what Newfield (2011) and others might describe as a ‘monomodal’ approach: I am simply drawing attention to the way that it differs from what takes place in the lecture theatre and the tutorial room. When I come to interview course tutors at the end of semester I might find there is a very good reason why measurements of understanding and ability rely on language in its different forms. For the time being however, I have three questions to reflect upon in the coming weeks and months:

Before that however I have a lecture on The Origins of the American Revolution. I expect there to be bullets, but no bullet points. References:

See also: Assessment, feedback and multimodality in Architecture Multimodality and the presentation assignment "I'm just glad it's not an essay!": a poster presentation assignment in music

The project New Geographies of Learning: distance education and being 'at' The University of Edinburgh set out to investigate how students participating in a fully online distance learning programme - the MSc in Digital Education - experienced and understood their university. Beginning in 2011, we spent a year gathering narrative and visual data, primarily through:

Our over-arching research question was: What does it mean to be a student at Edinburgh but not in Edinburgh, and what insight does this give us into learning design for high quality distance programmes? We addressed this question in two published journal articles:

More recently Sian Bayne, Michael Gallagher and I revisited the 21 digital multimodal postcards with an interest in exploring what they might tell us about the way that distance students construct and negotiate space for learning. Our approach and findings are described in a chapter 'The Sounded Spaces of Online Learners' within this recently published collection by Lucila Carvalho, Peter Goodyear, Maarten de Laat (2016):

To briefly touch on the way we approached the analysis of the postcards, we took a broadly multimodal approach which recognised that meaning emerged from the particular ways that the different semiotic resources came together in concert. This was augmented by looking towards Fluegge’s work around personal sound spaces (2011) from which we adopted and adapted the notions of territorialism, sonic trespass and spatial-acoustic self-determination. Within the visual realm meanwhile we looked to Rose’s 'site of audiencing' (2012). Our approach was also informed by Monaco’s ideas around coherence (2009) and similarly Van Leeuwen’s work in social semiotics around information linking (2004).

As we had hoped, by paying equal attention to the visual and aural (and the meaning that emerged from their juxtaposition), we gained fascinating insights into the ways that this particular group of students looked to construct and negotiate space. At times this challenged the conventional conceptualisation of distance learners, often depicted through a high level of mobility and digital sophistication. Instead we saw and heard the trappings of the domestic: family and soft furnishings; kitchen table and kettle boiling. We also became aware of how this group of students differently attempted to orchestrate or adapt to the material character of their surroundings. Without suggesting that our findings could be applied to online education across the board, we nevertheless believe that our methodology encourages teachers and course designers involved with online education to consider what is happening on the other side of the screen. Whenever I'm on campus I'm struck by the amount of attention that has gone into reconfiguring the different buildings into spaces that are conducive to learning. In comparison, there has been very little critical attention to the learning environments of online students. Through the findings and methodology described within our recently published chapter, we hope that we will encourage other researchers, teachers and programme designers to have a good look - and listen - to the learning spaces of online, distance students.

A digital postcard of Daisy's learning space in Xalapa, Mexico.

References:

See also: Away from the university Listening to the street Look! Listen! Learn! I was recently invited to make a video to accompany the Manifesto for Teaching Online (2016). The Manifesto comes from the team behind the MSc in Digital Education at the University of Edinburgh and comprises a series of short statements which articulate what it means to teach within digital learning environments. Whereas our work to put together the Manifesto was collaborative, the video should be seen as my own personal interpretation and response each of its 22 statements. Here's the newly completed video: Rather than trying to explain how I attempted to represent the different statements in the Manifesto, I'm instead going to describe how some of the key ideas around online education influenced my approach as I put the video together. To begin, reflecting the growing interest in the multimodal character of digital scholarship, I spent time thinking about how the particular configuration of images and sounds could work together in juxtaposition, or what Carey Jewitt (2009) has described as the way that meaning emerges from the particular relationship between different modes. This became quite an iterative process where I would start with a rough idea in response to a Manifesto statement, which would in turn prompt the gathering of field recordings, which then sparked a visual idea and subsequently led to the creation or collection of further sounds. Maybe the best example of this from the video is the ‘Digital Natives’ statement where I started off thinking about Bronislaw Malinowksi’s Argonauts of the Western Pacific (1922) and ended up burying a Nokia 5510 (1998) in a sandbox. Whereas the critical interest in multimodality is often concerned with focusing its gaze on the semiotic resources at work within a document, an artefact or a communicational event, sociomateriality asks us to pay attention to the ways that the wider milieu shapes our meaning-making practices. Therefore where some of the images/sounds in the video seem haphazard or untidy it should be seen/heard in light of what Fenwick et al. (2011) describe as:

I also wanted the video to itself provoke questions about digital authorship, ownership and plagiarism. For instance, what responsibility do we have to the author of a piece of work that we record and then remix beyond its original form or meaning? What are the ethical implications of adding reverb to someone's voice or recolouring their textile work? And how do the conventions of referencing and plagiarism that were conceived around words-on-the-page, take account of video and other digital formats? These are questions similar to those raised by Kathleen Fitzpatrick (2011) in her work around digital authorship and it seemed fitting that she should 'appear' in the video. Finally, as I prepared the video I also wanted to challenge the visual conceptualisations of online teaching which neglect the physical places where the corporeal bodies of teachers go about their scholarly business. Behind the virtual worlds, learning management systems and social media spaces that are often used as icons of online, there exists the campus, the cafe and the couch. These ‘teaching spaces’ are represented through sight and sound: an office on the 4th floor of St John’s Land in the School of Education; the space at home where I write and read and where I worked on the video itself. I hope you enjoy the video. References

Fenwick, T., Edwards, R. & Sawchuk, P. 2011. Emerging Approaches to Educational Research: Tracing the Sociomaterial. (Oxon, Routledge). pp. 1-18. Jewitt, C. 2009. An introduction to multimodality. In The Routledge Handbook of Multimodal Analysis. Jewit, C. (Ed) (London, Routledge): pp. 14-27. 'Kathleen Fitzpatrick: "The Future of Authorship: Writing in the Digital Age"'(2011) YouTube video, added by FranklinCenterAtDuke [Online]. Available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v4qq01Qskv0 (Accessed 12 June 2016) Malinowski, B. [1922}. Argonauts of the Western Pacific. Prospect Heights, 10 IL: Waveland Press, Inc. Pp. 1-25 (Introduction).

Last Thursday and Friday (16 & 17 June) I attended the Visualizing the Street Conference, hosted in Amsterdam by the ASCA Cities Project. Alongside my colleague Jeremy Knox, I presented a methodology for investigating the city that drew on multimodality and mobilities (including Kress & Parcher (2007)), combined with the growing scholarly interest in urban walking (including Richardson (2016)). Our methodology involved undertaking an unrehearsed dérive through the city where we set out to gather aural and visual data that would provide opportunities for thinking about our relationship with the city. This methodology involved arriving early in Amsterdam ahead of the conference in order to undertake our walk around the city, before reflecting on the data and then pulling it together into something coherent ahead of our presentation the next day. Perhaps the most interesting part of our approach was that, for the most part, our route through the city was guided by the sights and sounds that grabbed our attention, reflected in the video below.

As we reflected on our experience in the hours following the dérive, one of the ideas to emerge was that while we might see ourselves as freely exploring the city, our path was also shaped by weather, building work, hunger and also self-preservation as we attempted to negotiate a safe route between bikes, trams, mopeds and canals. We became part of the city's network, subject to its flows and varying rhythms: with more time for reflection we would like to have explored how sociomateriality and posthumanism might differently theorise our approach.

Another idea to emerge in conversation was the importance of paying attention to the aural character of our environment. As the acoustician Trevor Cox has recognised (2014), for a long time we have heavily privileged what we see over what we hear, meaning that the aural character of our environment is under-theorised and under-considered. In our approach we attempted to turn up the volume on the city, as we simultaneously gathered sounds and images on our phones. When we later came to review this data it became clear that focusing on a single mode sometimes provided an incomplete or at times misleading representation of the city. At the same time, by looking beyond the visual we gained a more complete appreciation of our surroundings in the moment that we gathered our data, or as I put it during our conference presentation:

Here are the slides from our presentation, although unfortunately without the accompanying field recordings that we played to accompany our discussion.

References:

|

Search categories

All

I am a Lecturer in Digital Education (Education Futures), within the Centre for Research in Digital Education at The University of Edinburgh.

@james858499 [email protected] |