|

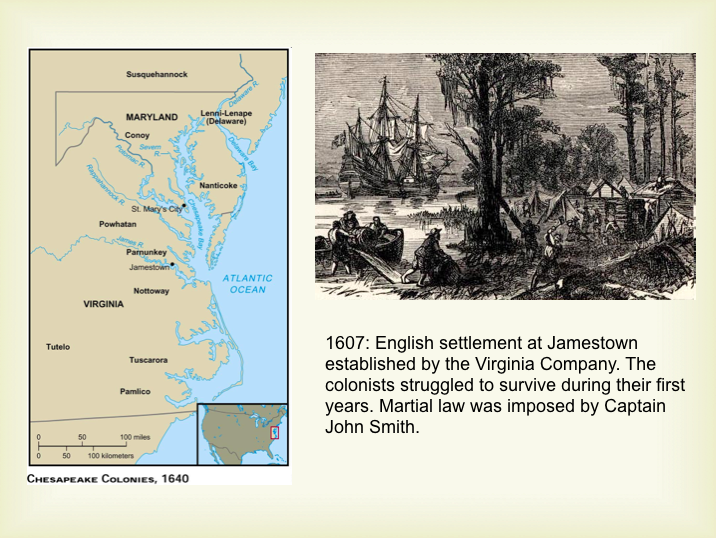

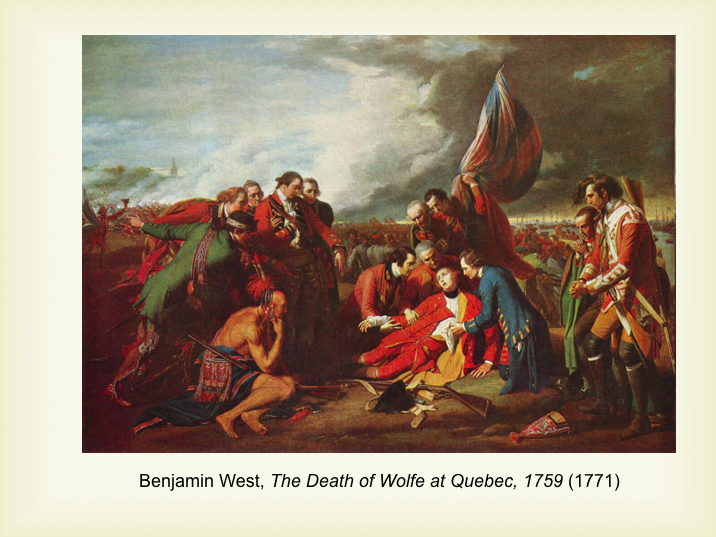

As part of my Doctoral research into multimodal assessment in the Humanities I am undertaking an ethnographic study of an undergraduate American History course. I observe lectures, tutorials and other situations where students and tutors gather to construct meaning, as they explore The Making of the United States of America. There are two reasons I wanted to spend time in a History class. First, in common with the majority of Humanities courses, assessment within History programmes tends to privilege language, commonly in the form of the essay. Second, with its interest in visual artefacts as a means of study - drawings, paintings, maps, photographs - History has an eye for the way that images contribute towards understanding. Bringing these two ideas together, I wondered whether History programmes might be open to assessment practice where attention is paid to the visual, multimodal character of student work. Now that I have reached the third week of the History course (and have a couple of hours before the next class), I am recording some early observations about the role that images have played within classroom teaching. To begin with some context, this is a second year undergraduate course drawing students from a range of degree programmes. Three times a week the lecture theatre is packed with an audience of around 300, augmented by tutorials with groups of around 12 students each. In all of the classes the tutors have used PowerPoint presentations, with images to the fore. Something that really stands out from my field notes is that these images are always more than a backdrop: they appear central to the knowledge that the tutor wishes to convey. For instance:

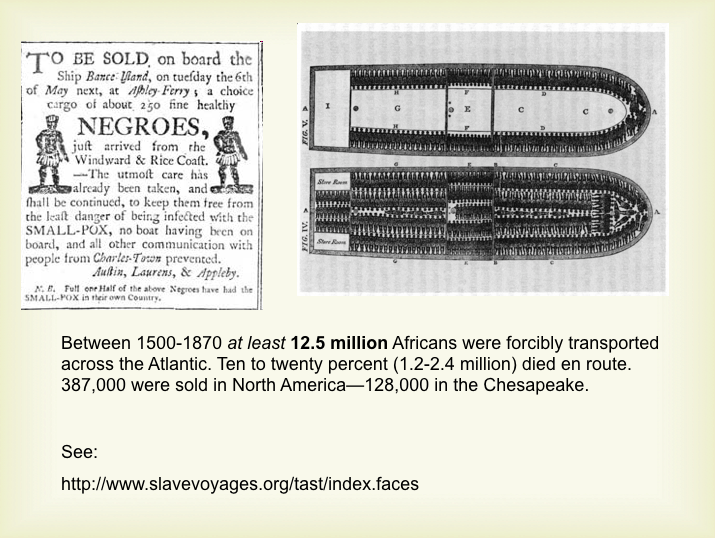

In these instances the images work alongside the oral delivery, adding colour and context to what is being said. This isn’t to suggest say the lecturer’s oration and wider performance is presented in monochrome: on the contrary it is enthusiastic and eloquent. Simply, the images are vital in helping the tutor to convey meaning. Click on images to enlarge. Slides reproduced with kind permission of Professor Frank Cogliano. On other occasions the images are themselves the central focus of study. Cartoon depictions of individuals and events are used to prompt students to reflect on competing perspectives and attitudes of the time. Newspaper adverts and notices, variously drawing attention to slaves-absconding-or-for-sale, are themselves historical artefacts that demand discussion within the tutorial setting. For the most part the images on screen are accompanied by reasonably small bursts of text (typed words), mostly single sentence captions providing factual information: title, subject, author, date and so on. Three weeks into the course and I have yet to face down a single bullet point. In terms of both prominence and placement, text immediately seems to perform a functional supporting role to the central positioning and critical purpose of the image. This however disregards the presence of text within many of the images: a political proclamation or newspaper notice may be presented in j-peg format however the conveyed meaning is heavily dependent on the use of text. If we narrow our gaze from the slide in its entirety to instead see an image as a communicational act in its own right, we become aware of the intricate assemblage of meaning conveying resources sitting in juxtaposition: text, font, colour, spacing, layout and so on. When this is combined with the tutor’s oral delivery (volume, tone, pitch, pace, silence) and physical performance (eye contact with the audience, gesture, posture, movement across the space behind the lectern) we see that the History classroom is richly multimodal (or ‘densely modal’ to borrow from Norris (2004)) in the way that meaning is conveyed and interpreted. Picturing Thomas Payne in the richly multimodal History classroom In contrast to the highly visual and multimodal character of meaning-making in the classroom, assessment for the American History course privileges the use of written language. Coursework comprises two conventional essays while 20% of the final mark is based upon a ‘practical examination’ in the form of a student’s contribution towards tutorial discussion. To be clear, I am not suggesting that the assessment design is flawed in taking what Newfield (2011) and others might describe as a ‘monomodal’ approach: I am simply drawing attention to the way that it differs from what takes place in the lecture theatre and the tutorial room. When I come to interview course tutors at the end of semester I might find there is a very good reason why measurements of understanding and ability rely on language in its different forms. For the time being however, I have three questions to reflect upon in the coming weeks and months:

Before that however I have a lecture on The Origins of the American Revolution. I expect there to be bullets, but no bullet points. References:

See also: Assessment, feedback and multimodality in Architecture Multimodality and the presentation assignment "I'm just glad it's not an essay!": a poster presentation assignment in music

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Search categories

All

I am a Lecturer in Digital Education (Education Futures), within the Centre for Research in Digital Education at The University of Edinburgh.

@james858499 [email protected] |